The Harmonists, founded by charismatic George Rapp (born Johann Georg Rapp, 1757–1847), fled Germany in 1804 for the United States to escape religious persecution. They grew to become one of the most influential communal societies in America, a model of industrialization yet with a rich spiritual life. They were internationally known, discussed in England and Germany and mentioned by Lord Byron in his 1819 epic satire Don Juan.

The Harmonists established two towns before returning to the region of their first settlement, western Pennsylvania. In 1804, they established their first American commune in Harmony in Butler County, and in 1815, they moved to southern Indiana and built New Harmony. In Beaver County, the Harmonists founded two cities, Economy and Beaver Falls. Here at Economy in 1824, they purchased three thousand acres along the Ohio River, the smallest acreage of their three settlements. The celibate members aged and the organization fragmented after the 1830s, but their productivity and wealth allowed them to function until 1905, guided by a series of savvy business leaders. The Harmonists ran several companies, built housing for workers, and introduced new industries. They also operated a museum and a hotel that were open to the public. Between 1824 and 1832, they built more than one hundred houses; a large sawmill; planing mill; cotton, woolen, and flour mills; and a church. Especially after the Civil War, they invested in oil, timber, and railroads in western Pennsylvania. The mark they left on Ambridge is apparent at every turn, not only in the red brick and frame structures that have been preserved by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania since 1916 but also in eighty other houses and businesses around the village dating from the period of the Harmonists' habitation (1825–1905).

The Ambridge site was named a National Historic Landmark in 1965. In 1990, architectural historian Michael J. Lewis, working for the Clio Group, and Marianna Thomas Architects produced a multivolume Historic Structures Report that is quoted in the following paragraphs. In 2003, an energy efficient Visitor Center opened to provide an orientation theater, classrooms, archives, and exhibition space. The gabled brick portions of the one-story building have espaliered grape vines similar to those on the Mechanics Building, discussed below. Sandwiched midblock northeast of the picket-fenced village, the center enhances the neighborhood rather than dominating it.

Frederick Reichert Rapp, adopted son of George Rapp and a stonemason by trade, designed most of the more elaborate Harmonist buildings and supervised the construction of all three towns, Harmony, New Harmony, and Economy. His drawings are preserved at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission's archives in Harrisburg. Rapp's architecture is unique, a product of conscious thought and decision making. He invented a new visual and functional system to balance the contradictions inherent in the Harmonists' existence. Their buildings had to accommodate a communal identity while allowing privacy for married couples and familylike groupings of adults; they had to show an

The Feast Hall facing Church Street embodies the Harmonists' communal and educational ideals. Accommodating offices below and a massive feast hall above, it resembles, in both form and plan, those of other pietist groups, especially the Moravians, whose buildings were an important model for the Harmonists. It is clear that the lower stories were meant as offices and spaces devoted to the mind, while the second floor was mystical and spiritual. With its elliptical ceiling and dimensions of 96 × 50 feet, there is still much to learn about how the Harmonists used this fantastic space flanked by balconies leading nowhere. The hall's first story held a collection of “natural curiosities,” and, as such,

The Harmonist community always honored its leaders with special residences. The house, as the parlor for the town of Economy, illustrates the richness of the immigrant experience by expressing an American identity but defiantly retaining its German character. George Rapp's house was built in 1825, and Frederick Rapp's by 1832. They were made to be joined and appear as one, illustrating the close relationship of subordination and affectionate attachment between the denomination's spiritual leader and its chief administrator-architect. The exterior of the house uses elements of the American Georgian (portico) and Federal forms (fanlight) with the German vernacular (jerkinhead roofline). Because the houses were constantly inhabited by Rapp's successors, they have been altered more than any of the buildings preserved in the village. Behind the formal facade, the rear elevation is irregular and dominated by a two-story veranda focusing on the river and the garden.

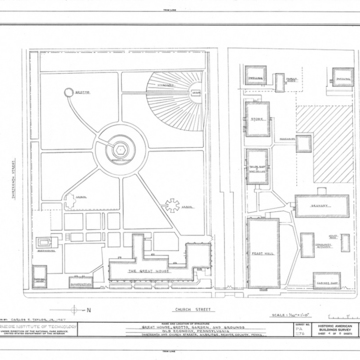

The garden west of Rapp's house was more than a source of herbs and flowers for the Harmonists. Each of the garden's four quadrants has different characteristics that may reflect the theological program of the communal society. All three of their towns focused on a garden, a grotto, and a maze. Here the Grotto (Einsiedeley) is a hermitage in the wilderness. Built of local yellow sandstone and granite with mud-pack mortar, the exterior of the cylindrical building with its conical thatched roof was deliberately primitive, but its interior reveals a smoothly plastered circular Greek Revival space, with a plaque honoring George and Frederick Rapp. Openings are located at each of the four compass points with a curved door fashioned from white oak bark.

The Granary, built in 1824 and one of the first buildings at Economy, is located within one hundred paces of the master's home. The Harmonists believed that the second coming of Christ was imminent, and, as such, they were vigilant about keeping a year's grain supply on hand for any disruption during the “transition to the new Jerusalem.” At 90 × 38 feet and four-and-one-half stories, the huge half-timbered building with rubble foundation was one of six granaries the Harmonists built in the United States, and one of only two remaining; the other is in New Harmony, Indiana. While a new building type was created for the Feast Hall, the Granary adheres to the conventions of late-eighteenth century vernacular German building types. The narrow southern facades and masonry first story kept the building cool; the frame upper story had louvered apertures to disperse moisture from the stored grain. By the 1890s, the granary had been remodeled twice.

A rare survivor of the brick structures that the Harmonists used for their factories is the Mechanics Building, which housed a wine cellar, tailor, shoemaker, and printing shops. The wine cellar, “a masterpiece of Harmonist masonry,” has deeply splayed light shafts, stone vaulting, and cut-stone floor slabs. Parallel tracks lining the exterior basement stairs allowed kegs to be rolled into place. The upper story has a central-hall plan with two rooms on each side.

A typical Harmonist house in Economy was made of brick or frame with three rooms inside: living room, sleeping room, and kitchen; corner stairs were in a separate vestibule, and most houses had a central chimney. Entrance doors faced the kitchen garden rather than the public street. Forty-three houses were built in Economy between 1825 and 1830. The Romulus L. Baker house, for example, was built for a prominent Harmonist, the storekeeper, and

At first glance, one might assume that the Harmonists' impact on the architecture of western Pennsylvania was regional and vernacular. Harmonist-trained carpenters built structures in Harmony, Beaver Falls, and Monaca; they built barns and utilitarian buildings to serve the industries they funded and housing for workers in those industries. Their stylistic choices were limited to the time of Frederick Rapp, and little new design work followed his 1834 death. Yet during the 1830s and 1840s, they were widely studied here and abroad for their adaptations to the Industrial Revolution. Their buildings are, as architectural historian Michael J. Lewis remarked in the Historic Structures Report of 1990, “an amazing collision of German vernacular building, modern neoclassical sources, American Georgian tradition and contemporary mill-building technology,” unique and amazingly well preserved.