Redwood Library, the first of Peter Harrison's three public buildings for Newport, carries the old colonial tradition across Bellevue Avenue, occupying a site which was, when built, on the high rim of the old town. In the eighteenth century it must have suggested an intellectual temple on an acropolis.

Elite intellectual and artistic life in early eighteenth-century Newport came to focus in the Philosophical Club. It spawned an informal group of leading citizens who gathered around Bishop Berkeley as their mentor and example while the bishop resided at Whitehall in nearby Middletown, from 1729 to 1732. They christened their new group the Society for the Promotion of Knowledge and Virtue by a Free Conversation. The idea of establishing a subscription library to perpetuate their “free conversation” was eventually propelled by gifts from two leading merchant-traders in town: one from Abraham Redwood, Jr., of 500 pounds for books and one from Henry Collins of land high on the perimeter rim of the densely inhabited slope down to the water.

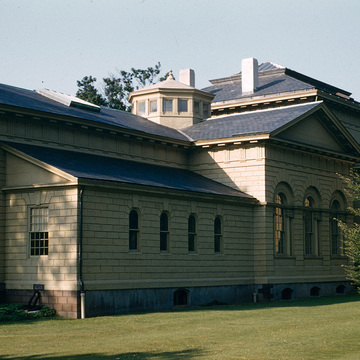

The detailed contract of 1748 for the library building, the only such document extant for any of Harrison's buildings, was signed by his brother Joseph while Peter was in London. Since Joseph, too, is known to have been a draftsman, he may deserve partial credit for the design. More likely, Peter sent basic drawings, at least, from London. In any event, he was clearly in charge during the later phases of construction after his return. Again he (and/or his brother and the building commission) leafed through the books in Peter's extensive library to choose as their format a design for a garden temple in a headpiece in Edward Hoppus's Palladio (1735), which reproduced a structure in Lord Burlington's garden at Chiswick. A similar design with an added dome was also reproduced in William Kent's Designs of Inigo Jones and Others (1727), where it was identified as a casino for Sir Charles Hotham by William Kent. Peter Harrison's library contained both books, and Redwood Library shows details lifted from both examples. The chosen model was a full-fledged temple with a Doric portico and with projecting wings, or “outshots,” one window wide, on either side immediately behind it to serve as offices. Their sloping shed roofs provided for the illusion of another pediment behind that of the entrance portico, which the body of the temple building cut through. Overall, the building was to be “plank'd … in Imitation of Rustick” (possibly the first use of the technique in the colonies, unless Shirley Place in Roxbury, Massachusetts, antedates it). Harrison could have derived the triple motif of a Palladian window under large arches which originally adorned the rear wall of his temple from a number of sources. A particularly popular motif in England, it appears in all the design books Harrison used for the portico. Whereas the style in front is Doric, it becomes Ionic on the original rear elevation, another indication of the method of designing from plates rather than conceptualizing the entire building as an entity. (When George Snell added a reading room to the rear of the original temple in 1858, he moved the triple Palladian motif to the side wall facing south and duplicated it on the opposite wall to the north while extending the “outshots” the full length of Harrison's temple in order to increase office space.)

As the first of Harrison's three public buildings in Newport, the Redwood Library betrays more awkwardness than either of the later ones, the Brick Market and Touro Synagogue. The interlock of the “outshot” pediment behind that of the temple is somewhat awkwardly joined and proportioned to the body of the building; the columns of the portico are a little squat for their spread; the portico with its full-width steps is somewhat too grand for what is behind. In sum, more than his other works, the library suggests too anxious copying from the sources. For Harrison was not, like Richard Munday, an artisan who invented, but a gentleman concerned with correctness and knowledgeable about what was then regarded as correct in London, where Lord Burlington (another gentleman amateur) and his circle made the classicism of Palladio the cachet for architectural design. There is some poignancy in the ambition of the colonial Tory to confer on the library (allegedly the seventh oldest in America) the impeccable grandeur of the first public building thoroughly committed to Palladian classicism in the colonies. Inside, furniture by Thomas Goddard