You are here

Vanderbilt Peabody College

Wealthy businessman George Peabody created the Peabody Education Fund in 1867 to provide education—primarily for teachers—in the post–Civil War South. The University of Nashville, which would evolve into the George Peabody College for Teachers, was the first college to receive assistance from the fund. In 1910 members of a newly appointed Peabody board decided to move the school to a site adjacent to Vanderbilt University, with whom the school already had a working relationship. Four years later, this new campus was complete.

The New York architectural firm of Ludlow and Peabody was chosen to design the overall plan of the new campus, along with several of its major buildings. Nonetheless, credit must also be given to Bruce R. Payne, who was appointed president of the college in 1909. Previously employed by the University of Virginia, Payne wanted the Peabody campus modeled on Thomas Jefferson’s scheme for Charlottesville.

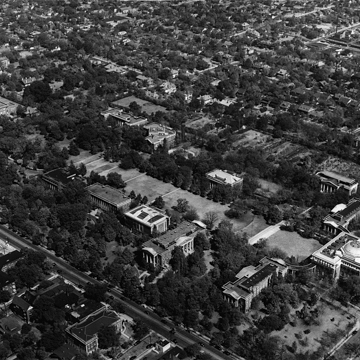

In Nashville, the campus was composed of a landscaped mall with allées of trees flanked by brick buildings. While this “academical village” concept reflected Jefferson’s precedent, it also embodied the values of the American Renaissance, which had prompted a renewed interest in classicism at the turn of the century.

William Orr Ludlow (1870–1954) and Charles S. Peabody (1880–1935)—no relation to George Peabody—were well-versed in the classical language of architecture and planning. Ludlow had worked with Carrère and Hastings, while Peabody studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Within a year or so of forming their partnership in 1909, Ludlow and Peabody secured the commission to design Peabody College. By 1915, Ludlow and Peabody’s Industrial Arts, Home Economics, Psychology, and Social Religious Buildings were completed.

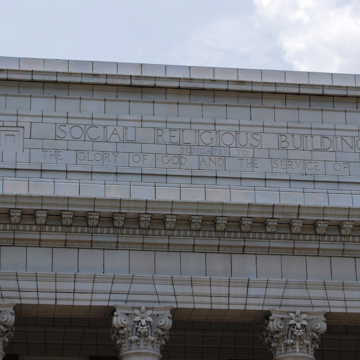

The buildings are arranged around a central campus green space and are tied together through the use of red brick, heavy stone columns with Ionic and Doric capitals, and multi-light windows. The most spectacular of the first group of buildings to be completed is the Social Religious Building, funded in part by John D. Rockefeller. Clearly intended to evoke Jefferson’s Rotunda at the University of Virginia, the brick and glazed tile edifice is an impressive sight, and the focal point of the south end of the green. Its domed chamber rests on a three-story classical base defined by monumental stone columns with Composite capitals. Smaller portico entries are composed of engaged Ionic columns carrying a stone pediment. Arched transoms with keystones over French doors and multi-light windows embellish the facade. Incised on the cornice of the main facade is “Social Religious Building Dedicated to the Glory of God and the Service of Man.”

Sitting on a slight rise at the head of the quadrangle, the East and West Dormitories are connected to the Social Religious Building by gently curved colonnaded hyphens, another reference to Jefferson’s plan for the University of Virginia. Other buildings at Peabody flank the main grassy space, while walkways lead to secondary green spaces and later buildings. Though designed by different architects, these later buildings of Peabody’s historic core sit comfortably in the original plan and are compatible in terms of materials and massing with Ludlow and Peabody’s earlier work.

Among these later buildings is the Carnegie Library, which represents the largest single grant ($180,000) that Carnegie made to an American college. It was designed by New York architect Edward Tilton and completed between 1917 and 1919. Like Peabody, Tilton learned his classicism at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. The library is situated at the north end of the campus and is distinguished by its pedimented entry, Ionic columns, and arched windows adorned with stone scrolls. A distinctive feature of the library is the blocks at the top of the cornice on the north elevation with “GPCT” for George Peabody College for Teachers.

During the 1920s there was a major push to complete the Peabody campus. In 1922, for example, the General Education Board, a philanthropy founded by John D. Rockefeller and Frederick T. Gates, provided funds for three new buildings. The Demonstration School (1925) provided spaces for classes in course planning and teaching. McKim, Mead and White designed the Administration Building (1925) and the 1928 Cohen Building. The firm, based in New York City, was nationally known for its classical and Beaux-Arts work, making it an obvious choice for additions to the Peabody campus. Also part of this building campaign was a dormitory designed by Nashville architect Henry Hibbs, who was well regarded in the southeast for his collegiate architecture, including buildings in Davidson College in North Carolina, Fisk University, and across the street at Vanderbilt University.

Peabody College merged with Vanderbilt University in 1979 and twenty-two historic buildings spread across some fifty-five acres remain part of the university today.

References

Conklin, Paul K. Peabody College: From a Frontier Academy to the frontiers of Teaching and Learning. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2002.

Herndon, Joseph L. “Architects in Tennessee until 1930: A Dictionary.” Master’s thesis, Columbia University, May 1975.

Jones, Robbie D. “‘What’s in a Name’ Tennessee’s Carnegie Libraries & Civic Reform in the New South, 1889-1919.” Master’s thesis, Middle Tennessee State University, 2002.

Kreyling, Christine. “Great Aspirations: Campus Architecture Reveals its Past and Informs its Mission.” Vanderbilt University. Accessed April 5, 2018. http://cpc.vanderbilt.edu/.

Kreyling, Christine, Wesley Paine, Charles W. Warterfield, Jr., and Susan Ford Wiltshire. Classical Nashville: Athens of the South. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1996.

“The Peabody School of Library Science: Contributions to Librarianship in Tennessee.” Tennessee Library Association. Accessed April 5, 2018. http://www.tnla.org/.

Rettig, Polly M., “George Peabody for Teachers,” Davidson County, Tennessee. National Historic Landmarks Form, 1976. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.