You are here

Western Mental Health Institute

The Western Mental Health Institute is a historic insane asylum located in the small town of Bolivar, about sixty miles east of Memphis. The institution is anchored by the main administration building, a Gothic Revival landmark designed in the mid-1880s on the Kirkbride Plan. The facility is commonly known as the Western State Mental Hospital, or simply “Western State.” Constructed in 1886–1889, the asylum was the last of Tennessee’s three major mental hospitals built in the Victorian era, and the only one to remain in operation. Western State’s main administration building is one of the most significant examples of Gothic Revival institutional architecture remaining in Tennessee.

The architects of Western State were the brothers Harry Peake McDonald (1848–1904) and Kenneth McDonald (1852–1940) who practiced together in Louisville, Kentucky. Harry P. McDonald formed the firm in 1880 with his brothers Donald and Kenneth. A Confederate veteran from Virginia, Harry graduated with a degree in civil engineering from Washington and Lee University in 1869 before relocating to Louisville in the 1870s. Western State was the firm’s first commission in Tennessee.

The McDonald Brothers opened a branch office at Memphis in 1887 and won commissions across the state, including the First Cumberland Presbyterian Church (1888) at McKenzie; the Tipton County Courthouse (1890) at Covington; Union Depot (1893) at Memphis; and the Sevier County Courthouse (1895) at Sevierville. The firm had previously designed the Southwestern Lunatic Asylum (1885-1889) in Marion, Virginia.

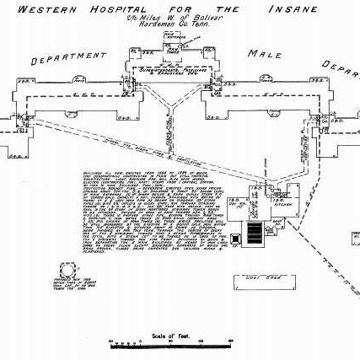

The McDonalds based the design of Western State on the Kirkbride Plan, a standardized method of asylum construction and mental health treatment advocated by Philadelphia psychiatrist Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809–1883). In 1847, the New Jersey Lunatic Asylum became the first institution built on the Kirkbride Plan; soon they were built throughout the country.

Unique architectural elements of the Kirkbride asylums include long wings arranged in a staggered, tiered plan so each connected building received sufficient sunlight and fresh air as well as privacy for the patients and views of the grounds. Male and female patients were housed in their own wings, separated by a central administrative core with offices, support facilities, and staff apartments. Each wing was subdivided into wards separated by polygonal stair towers. As part of the therapeutic treatment method, asylums on the Kirkbride Plan were located in secluded sites with expansive grounds, landscaped gardens, and farmland.

At Bolivar, the state’s site commissioners selected a rural hilltop farm about two miles west of downtown. Construction of the $250,000 four-story facility included rooms for 300-350 patients. The facility opened in December 1889 with 156 patients transferred from Nashville. Like most other Kirkbride Plan asylums, Western State was built in the Gothic Revival style and is characterized by steeply pitched hipped and polygonal roofs, corbelled brick cornices with molded brick eaves, ornamental stone water tables, jerkinhead dormers, arched windows, and a one-story porte-cochere entrance with pointed arch openings. The interior features multi-colored tiled floors, vaulted ceilings, pressed tin ceilings, a turned wood stair, and a marble builder’s plaque.

The state-owned 798-acre facility at Bolivar was largely self-sufficient and grew from a few hundred patients in the 1890s to over 3,200 patients and 250 staff members by 1960. In 1910, the main administration building’s male wing was enlarged and in 1927 a new, two-story dining wing and auditorium was built at the rear. Additional buildings were constructed between the 1920s and 1950s.

Tennessee’s segregationist policies were manifest at Bolivar in the separate, two-story “Negro Ward” the state built for African American patients in 1895–1896. This was expanded in 1913 with a two-story dormitory for African American staffers. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Negro Ward was expanded with separate buildings for administration, laundry, and receiving patients. In 1948, the original hospital building from 1895–1913 was razed and replaced with a three-story, mid-century modern building called Luton Hall.

The sprawling Gothic Revival landmark was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987 as part of the Western State Mental Hospital Historic District. The following year, the state razed the three-story east and west patient wings of the main administration building, leaving the original four-story central tower and 1927 two-story rear wing. In 2008, the state demolished several historic buildings, including the 1927 Physician's Apartment Building and two 1920s staff houses in order to construct a modern state-of-the-art $58.5 million psychiatric hospital, opened in 2010.

Today, Western State serves around 2,500 patients across 24 counties, although only 250-300 of them reside on campus. Many historic buildings are vacant and in disrepair. With a staff of 650 and an annual budget of approximately $35 million, Western State is the largest employer in Hardeman County.

References

American Institute of Architects. “H.P. McDonald, FAIA, Obituary.” Quarterly Bulletin, 5, no. 2 (July 1904): 383.

Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation. Grains of Sand: A History of Western Mental Health Institute, 1886–1986. Bolivar, TN: Department of Mental Health & Mental Retardation, 1986.

Jones, James B., and Claudette Stager, “Western State Hospital Historic District,” Bolivar, Hardeman County, Tennessee. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1987. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.

Jones, Robbie D. The Historic Architecture of Sevier County, Tennessee. Sevierville, TN: Smoky Mountain Historical Society, 1996.

Sanborn Map Company, Bolivar, Tennessee, 1891, 1913, 1941.

Yanni, Carla. The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.