You are here

Thomas Hughes Free Public Library

The Thomas Hughes Free Public Library was built in 1882 as the first purpose-built library in Tennessee and one of the first freestanding libraries in the South. It served the small and isolated town of Rugby, located on the rugged Cumberland Plateau of East Tennessee about seventy-five miles northwest of Knoxville. This short-lived utopian resettlement community for British colonists was founded by author and reformer Thomas Hughes, to whom the library was dedicated.

Oxford-educated lawyer, judge, and author, Thomas Hughes (1822–1896) is best known as the author of the novel Tom Brown’s School Days (1857), a semi-autobiographical account of Hughes’ years as a student at England’s Rugby School in the 1830s. A committed social reformer, Hughes was heavily involved in the Christian Socialist movement. He was also appointed a Queen’s Counsel and served in Parliament as a Liberal from 1865 to 1874, drafting legislation that assisted trade unions and the working classes.

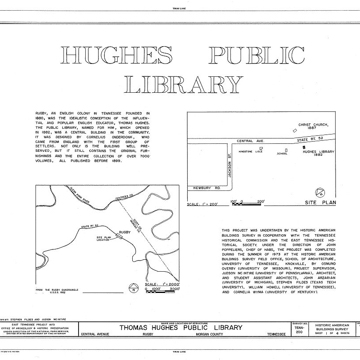

Hughes founded Rugby in 1879 as an experiment in utopian living for the younger sons of English gentry, providing them an opportunity to own land and be self-sufficient. That same year, the Boston-based Board of Aid to Land Ownership selected the 1,300-acre town site for Rugby straddling Morgan and Scott counties in Tennessee, and hired civil engineer and surveyor Rufus Cook (1815–1880) of Newton, Massachusetts, to design a town plan. Cook supposedly based the curvilinear town plan on the romantic landscape designs of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, such as Riverside, Illinois. Rugby’s Central Avenue, which later evolved into State Route 52, connected the community’s disparate commercial, institutional, agricultural, recreational, and residential areas. Public and commercial buildings were erected at the center of the town, including the Tabard Inn, Christ Church Episcopal, Board of Aid offices, and a Commissary. Hughes himself was on hand for a town dedication ceremony in October 1880 and within a year Rugby boasted 300 residents and at least a dozen new buildings, including Kingstone Lisle, set aside for Hughes who made annual visits through 1887.

George A. Fuller (1851–1900), an architect from Boston who relocated to Chicago in 1882, was responsible for Rugby’s earliest buildings, picturesque examples of Gothic Revival architecture inspired by Alexander Jackson Davis and Andrew Jackson Downing. By 1884, the colony had grown to include 65 buildings, most of which were modest in size and featuring steeply pitched gabled roofs, molded window hoods, decorative bargeboards, and board-and-batten wall coverings. Most houses occupied generous pastoral lots within walking distance of the community buildings.

Erecting a freestanding public library in the town was the idea of Dana Estes, a partner in the noted Boston publishing firm Estes and Lauriat (later Houghton-Mifflin). Between 1879 and the library’s opening in 1882, Estes single-handedly secured the donation of over 5,000 volumes from book publishers and librarians across the U.S., including William Frederick Poole of the Chicago Public Library.

Poole asked noted Chicago architect William H. Willcox (1832–1929) to design the Rugby library and his plans arrived in November 1881. A native of Brooklyn, New York, Willcox relocated to Chicago where he worked briefly for Dankmar Adler before opening his own firm in 1872; a decade later he moved to St. Paul, Minnesota. Willcox also designed libraries for Cairo (1883) and Peoria (1887), both in Illinois, but is perhaps best known for the Renaissance Revival Nebraska State Capitol (1881–1888), which was replaced by Bertram Goodhue’s iconic tower.

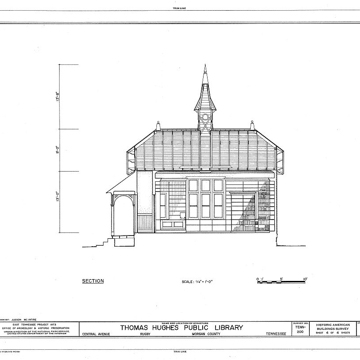

For Rugby, Willcox designed a fire-proof “rubble stone” library, but limited funds (the budget was $1,500) required construction of a frame structure situated sufficient distance from other buildings to limit the threat of fire. In the spring of 1882, Rugby builder J.S. Winkley, originally from Boston, erected the structure. As built, the library is a small, rectangular building measuring 35 by 22 feet and featuring a jerkinhead gable roof covered with standing seam metal panels and supported by solid sandstone foundation. It has a ridgeline mounted steeple marked with a trefoil motif, side gables with decorative bargeboards, and clapboard siding decorated with modest Gothic Revival trim. The main facade features an arched stained-glass window above a hipped roof, center-bay entrance portico protecting double entrance doors with arched glass panels embossed with the name of the library.

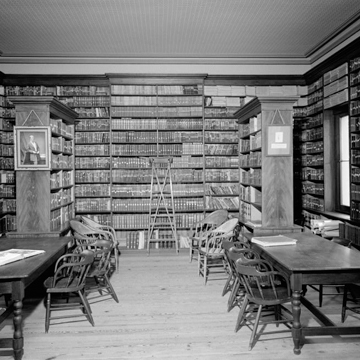

The library was completed in May 1882. The first librarian was Eduard Bertz, a German immigrant educated at Tübingen University who had arrived at Rugby in the fall of 1881. Books began to arrive immediately and the library formally opened on October 5, 1882. Assistant librarian Margaret Percival replaced Bertz as head librarian in 1883 and served in that capacity for many years. Leading members of the American Library Association, including Melvil Dewey and Charles Ammi Cutter, mentored the Rugby librarians, influencing the library’s organization and circulating policies. Within a few years, the one-room library was filled with over 7,000 volumes, dating from 1687 to 1899, and 1,000 periodicals. Bertz published a book, Das Sabinergut, about his experience at Rugby in 1896.

The Rugby library bolstered the spirits of members of the isolated community, most of whom were unaccustomed to manual labor and unprepared for such setbacks as legal issues and a typhoid epidemic. Despite the anchoring institutional presence of the library, the Rugby community never succeeded and most of the original colonists had died or left by 1888. The library, however, survived, unaltered from its completion in 1882. The interior has never been renovated and the original book collection is intact. Today, the Thomas Hughes Free Public Library at Rugby is the oldest intact nineteenth century public circulating library in the country.

References

Egerton, John. “Rugby.” Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Version 2.0, Online Edition. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 2000–2018. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/.

Jones, Robbie D. “‘What’s in a Name?’ Tennessee’s Carnegie Libraries & Civic Reform in the New South, 1889-1919.” Master’s thesis, Middle Tennessee State University, 2002.

Frank, J.J. Miele. “Rugby Historic District,” Morgan and Scott counties, Tennessee. National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, 2000 (draft). Copy on file at Tennessee Historical Commission, Nashville, Tennessee.

Stagg, Barbara. Images of America: Historic Rugby. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Press, 2007.

Stagg, Brian L. “Rugby Colony,” Morgan and Scott counties, Tennessee. National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1972; revised 1991. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Tinker, Nancy. “Thomas Hughes Free Public Library,” Morgan County, Tennessee. National Historic Landmark Nomination Form, 2007 (draft). Copy on file at Tennessee Historical Commission, Nashville, Tennessee.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.