You are here

The Lodge at Zion National Park

Opened in 1924, the Lodge at Zion National Park in southwestern Utah was an experiment aimed at promoting railroad expansion and tourism in the American West and its new national parks. It represents a historic private-public partnership between the Utah Parks Company and Zion National Park. Zion Lodge was the one of several projects by the National Park Service (NPS) to constitute a new architectural vocabulary in a style that came to be called NPS Rustic—a style that dominated NPS architecture during the 1920s and 1930s.

The Zion Lodge was born of three interdependent elements of early-twentieth-century modernity: the expansion of railroads, the rise of middle-class tourism, and the reframing of wilderness for popular consumption. In order to put Zion on the tourism circuit, NPS Director Stephen Mather approached the Union Pacific Railroad, the most powerful entity in the region, and proposed that they establish and operate all concession facilities in the park. Railroad concession monopoly had been effective at other parks and was a catalyst in transforming the formidable American landscape into visitor-friendly parks. The Union Pacific delegated the responsibility to a subsidiary business, the Utah Parks Company, which envisioned Zion as part of a “Grand Loop” tour of national parks in the entire American West. The commission for Zion Lodge was part of an ambitious plan of improved roads, standardized quality accommodations, and tourist facilities at Zion National Park and beyond. Zion’s property was bought and developed by Utah Parks Company under the supervision of the NPS. California-based architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood, who was involved in a number of park development projects, was selected to design the lodge.

The Zion Lodge was a key component of a new system of interconnected local and regional infrastructure. Accommodations consisted of a large central lodge with restaurant and gift shop that was surrounded by a number of freestanding cabins. Informed by the eclecticism of the era, Underwood conceptualized his architectural intervention in terms of suitability to program and site and he envisioned a design that would enhance the “rawness” and “spectacle” of the landscape. The nature-culture polarity of high styles was put aside for a cultural intervention that blended into the landscape in the manner of vernacular architecture. Underwood did not follow the Native American motifs made popular a few years earlier by Mary Jane Colter in Grand Canyon National Park and throughout the Southwest. Instead he recalled the siting strategies, scaling conventions, and materials used by the early European settlers in the American West, who did not have the resources to ignore the geography and environmental conditions of the region.

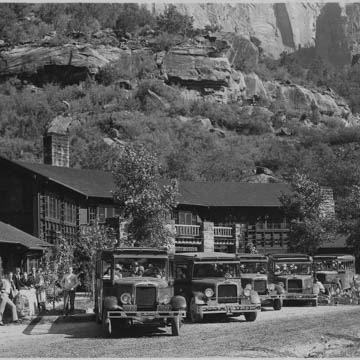

The main building was situated deep inside the park on the canyon floor, about two-and-a-half miles up the canyon and surrounded by a landscape of cottonwood plantings and a cactus garden. Wild trees, shrubs, and grasses were designed to screen the lodge (and the building complex around it) from the thoroughfare and long-term parking. The slopes were dotted with sagebrush, pinyon pine, juniper, and yucca. Underwood designed a low horizontal building with sloping roofs to fit in with the surrounding vegetation and contrast with the towering cliffs around it. In 1927 and 1929, he added deluxe cabins and girls’ dormitories a short distance from the lodge; these additions were tucked under the canyon walls in separate, small buildings on a curve around cleared ground.

The site plan was designed for pedestrian and vehicular traffic, in a manner reminiscent of a colonial village square. To enhance the rustic appearance, Underwood selected local materials, such as the reddish and tan-colored Navajo sandstone for which Zion Park is known, as well as timber. The wooden segments of walls were made of local rough-sawn lumber with a “studs-out” construction, reminiscent of the granaries built by the Mormon farmers when they first arrived in the region. Overscaled beams, rafters, and eaves extended beyond the walls and the edges of the roof, referencing the crude construction techniques and simple tools used by early settlers. Similarly, the sandstone was lightly dressed and the timber lightly varnished. Rock was used for smaller blocks and lower sections of the buildings. Rough, thick, and uneven mortar between stones of varying sizes and uneven facing recalled freshly quarried piles of rock. Milled timber exposed the variety of natural grain and enhanced the innate warmth of the material. Extensive use of hand labor and irregular use of materials recalled the first encounters of the European communities with the expansive American landscape. Likewise, exposed joinery and asymmetrical planning codified their architectural response as quintessentially American. The structure forsakes all applied ornament, instead featuring the colors and textures of the natural environment. The cabin walls were made with milled planks laid flush. In the cabins, massive stone chimneys create an ambiance of proximity to primordial nature.

The “honest” use of materials and the informality of joinery and detailing were extended well beyond the lodge and cabins. Through the 1930s, other structures including checking stations, ranger stations, ranger residences, campground stores, employee dormitories, shops and garages, trails, bridges, and even toilets, were built in the same style. The rustic style has also been applied to every constructed element in the parks such as gates, campsite fireplaces, water fountains, paths, retaining walls, and curbs. Underwood’s biographer describes the style at Zion as a “lighter rustic” than had been developed in the parks prior to the establishment of the NPS in 1916. Like any other style, it combines aesthetic and rhetorical functions. Use of the rustic style was intended to intensify the experience of being in nature, making it accessible to visitors who would otherwise never explore the sheer beauty of landscape.

The original lodge was destroyed by fire in 1966. It was rebuilt with a prefabricated structure on the same foundation until a 1990 remodel restored its original appearance. The cabins were updated in 2010 with modern materials, plumbing, and electrical components and systems, although they retained their original appearance. The Lodge also now features new environmentally conscious practices such as the use of renewable wind power for all of its electricity needs.

References

Clark, Gregory. “Remembering Zion: Architectural Encounters in a National Park.” In Observation Points: The Visual Poetics of National Parks, edited by Thomas Patin, 40-47 .Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Harrison, Laura Soulliere. “Architecture in the Parks: National Historic Theme Study.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, November 1986.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.