Eero Saarinen described the design for the Dulles terminal as “a strong form between earth and sky that seems both to rise from the plain and hover over it,” and “a huge, continuous hammock suspended between concrete trees.” The dramatic form with huge piers and sloping roof captured the Zeitgeist. Saarinen, who died ten months before its completion, created a new monumental gateway to the capital of the United States and, from the

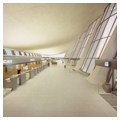

Unfortunately, Saarinen could not foresee the many changes that would come in the late twentieth century: security check-in; “hubbing”; the proliferation of commuter airlines, which require means of access other than mobile lounges; mammoth jetliners; waiting areas; and, indeed, the vast expansion of air travel. Along the rear of the terminal SOM designed a 50-foot-wide corridor and an ungainly box at mid-field that became the terminal for long-distance jets, with mobile lounges to ferry passengers back and forth. Saarinen's concept of the terminal itself as expandable has been achieved with a 600-foot addition by SOM (1995–1997) that doubles the original length. The extension—or, really, extrusion—of the original actually makes the building more commanding against the backdrop of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A new mid-field terminal by HOK has an appropriately subservient exterior and a bright and airy interior. Slated for obsolescence are the mobile lounges. Hailed at its completion and ever since as one of the great modern buildings, the terminal itself remains a thrilling architectural space and an aesthetic delight.

The area surrounding Dulles Airport is booming as a corporate center. New buildings are announced with amazing frequency, and a few are of interest. In addition to CIT (preceding entry), see also the National Reconnaissance Office (1988–1993, Dewberry and Davis; 14765 Lee Road), observable from Virginia 28 (Sully Road), adjacent to Dulles. The striking blue glass and metal structures do not hide very well this supposedly “secret” governmental agency.