An important example of a rural cemetery, Hollywood originated in 1847 when a group of Richmonders sought to create a picturesque cemetery on a narrow tract of rugged terrain with spectacular vistas of Richmond. They commissioned John Notman of Philadelphia, a Scottish-born and -educated architect, who had designed Mount Laurel Cemetery in Philadelphia and Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. After overcoming opposition in the Virginia General Assembly to granting a charter, the Hollywood Company began work on the project in 1848. The chapel marks the original entrance to Hollywood and the beginning of the area planned by Notman. Basically the plan encompassed a ravine running north-south and four hills on its west side. Although Laurel Hill was decidedly classical in plan, here Notman chose to work with the natural lay of the land, and Hollywood is more picturesque. Notman laid out the cemetery by walking the site and employing a topographical survey; he suggested the name because of the site's many holly trees. Notman's plan served as a template the Hollywood Company used for later expansions to the cemetery.

Initially Richmonders were skeptical, and few lots were sold in the early 1850s. However, the re-interment there of President James Monroe in 1858 firmly established the popularity of the

The tour of the cemetery can be driven or undertaken as a fairly vigorous walk by following the blue line on the pavement. Visitors are cautioned to observe the rules of the cemetery posted at the gates.

The Superintendent's House (1894, George P. Barber; W. A. Chesterman, builder), a rambling Queen Anne dwelling, replaced an earlier structure for the superintendent. Chesterman owned a small planing mill in Richmond and also built houses. Apparently he ordered plans from Knoxville architect Barber, who had recently published The Cottage Souvenir (1888). The house built at Hollywood Cemetery has all the Barber trademarks of several different roof forms, including a clipped gable; a tower topped by a cupola; and a wide porch. The Hollywood Cemetery Chapel (1877, Henry Exall; 1897, Marion J. Dimmock), designed by an English-born and -trained architect, began as a Gothic “ruin” straddling the original entrance; the southern portion is still visible. The practical needs of the cemetery eventually outweighed the aesthetics of a ruin. Dimmock employed the northern portion of the ruin as the base of the tower and attached a chapel. The original entrance to the cemetery is marked by the ornamental iron gates. The present cemetery gates were constructed in the early twentieth century.

The Confederate Section and Confederate Monument (1863, burial lots; 1867–1868, monument, Charles H. Dimmock) was acquired and laid out in an impromptu manner to accommodate the war dead. In 1866 the federal government decided not to allow the burial of Confederate soldiers in national cemeteries. In response, the Hollywood Ladies' Memorial Association organized what is credited with being the first Memorial Day celebration. The association commissioned the monument, one of the earliest Confederate monuments in the South. The rough granite pyramid perfectly captures the picturesque aesthetic of early Hollywood and met the financial limitations of the immediate postwar era. In 1869 the Ladies' Memorial Association reburied the majority of southern dead from the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Over the course of the late nineteenth century the Confederate Section was the setting for a number of events to memorialize the Lost Cause. The speaker's stand (1876) and the Pickett Monument are other noteworthy features.

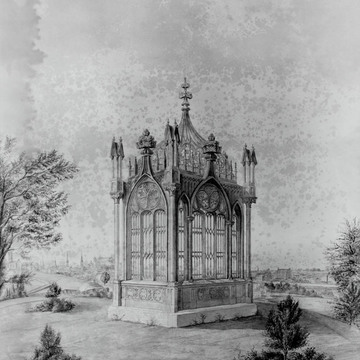

Ellis Avenue (c. 1850–c. 1870) affords some of the best vantage points for viewing funerary art and architecture. Included in the area is an impressive array of statuary, columns, ironwork, obelisks, and Gothic Revival monuments. Ellis Avenue also provides a central point for viewing Notman's plan. The Weddell Monument (1950, Charles Gillette, landscape architect) was designed for Ambassador Alexander and Virginia Weddell's landscape architect, who worked on their Virginia House (see entry, below).

The Monroe Monument and Circle (RI251.1) (1858, Alfred Lybrock) resulted from an effort to gain popularity and respectability for the cemetery. The Hollywood Company donated this circle at the southwest