St. Joseph Cathedral is the capstone of a remarkable building campaign conducted by Roman Catholic Bishop John J. Swint. During his forty-year term (1922–1962), Swint oversaw the building of more than forty churches throughout the Diocese of West Virginia. Pittsburgh architect Edward J. Weber, with whom the bishop collaborated, designed several of the largest and most important, and St. Joseph, built on the site of a predecessor cathedral, is easily their masterpiece. To the right of the main entrance, next to the base of the door jamb, is a small stone lightly and poignantly carved with the architect's name, followed by the letters OPM, for the Latin Ora Pro Me (pray for me).

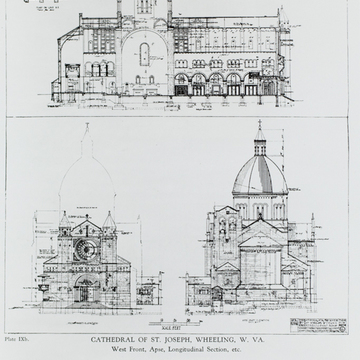

Dimensions of 200 feet by 67 feet make St. Joseph Cathedral one of West Virginia's largest churches. When the cathedral was completed, the design was described in the dedication program as being “strictly according to the best traditions of the Lombard Romanesque.” Weber used both general and specific motifs from a number of Italian sources. The central portion of the facade, with its recessed, arched entrance, arcade, and wheel window above, recalls the church of San Pietro in Toscanella, which the architect illustrated in his 1927 publication Catholic Church Buildings.

The sculpture in the tympanum of the main doorway, depicting Christ in Majesty, was carved by Francis Aretz, who also sculpted the Stations of the Cross inside. Carved symbols of the Four Evangelists occupy quadrants around the wheel window, as in the Toscanella church, and a statue of St. Joseph stands above. The exterior pulpit and sounding board, both of stone, on the northeast corner of the facade derive from examples such as the cathedral in Prato, near Florence.

In 1923, when plans were being developed, Bishop Swint sent the architect a slide of the cathedral of Santa Maria dei Fiore in Florence, which Weber promised to use in designing a lantern for the dome of St. Joseph. The massive dome that rises above the crossing from an octagonal drum does indeed recall the Duomo in Florence, as does the elegant open cupola on top. Originally, as in Florence, the dome was roofed with red tile; the current standing-seam metal covering is a replacement. The rounded, sculptural forms of the three apses, with their corbel tables, recall similar forms in the Basilica of San Vincenzo in Milan (also shown in Weber's book) and illustrate the architect's precept that “there should be no such thing as a rear to a Catholic Church.… The sanctuary end and the sides should be as well designed as the main facade.” A belfry tower at the southeast corner, between transept and apse, is not visible from the street.

Even with its obvious, honestly confessed borrowings, the church is a unique work of art. In Catholic Church Buildings, Weber cautioned against the “slavish copying of old buildings or old styles of architecture.” Asking rhetorically, “How shall we close our eyes to all that has gone before?” he advised that “one's imagination need not be stifled in the least” by using past models for inspiration. His attitude and approach are particularly evident in the colorful interior, where, as he stated in his Catholic Ecclesiology, decorations were “carried out in the spirit of the Mediaeval Byzantine style.” The long, broad nave is covered with a barrel vault decorated with colorfully painted trompe l'oeil coffers. A free-standing ciborium, another feature typical of Lombard Romanesque churches, protects the marble high altar. A mural titled Enthroned Christ and the Communion of Saints fills the half dome of the semicircular apse. Felix B. Lieftuchter painted it and the other frescoes, including those in the dome over the crossing. George W. Sotter, one of the leading exponents in the revival of medieval-inspired stained glass in America, fabricated the windows.

In 1973 the interior of the church was rearranged to accord with liturgical standards promulgated by the edicts of Vatican II. In 1995–1996 the cathedral was restored, its art works were cleaned, new HVAC systems were installed, and a new pulpit, altar, lectern, cathedra, and font were constructed from designs by Tracy R. Stephens. At the same time, reflecting Wheeling's population losses in recent decades, three churches were deconsecrated and their parishes consolidated into St. Joseph Cathedral Parish. During the 1990s work, remains of a stone column from the first cathedral were found under the present building. They were