When it was completed in 1929, the Lovell “Health House” in Los Angeles, designed by Richard Neutra, joined the ranks of the world’s modernist masterworks. When Austrian-born Neutra arrived in Los Angeles in 1925, he met the physician Philip Lovell through Rudolph Schindler, who, in addition to Lovell’s beach house, had already built two small, later destroyed, vacation houses for him in the mountains and the desert. While Lovell would always insist that he admired Schindler’s artistic creativity, he had doubts about his engineering and managerial skills. Even for the beach house, Lovell was amazed that Schindler never did working drawings or standard construction documents—areas in which Neutra was a master—and he acknowledged that his building was approved by Newport Beach only because a sympathetic official admired Schindler’s conceptual drawings and was curious to see how such a building would turn out. For his larger, more complex city house on a difficult sloping site, Lovell believed he could not take such risks and turned to Neutra for what he saw as his combination of technical expertise and creative compositional skills.

Neutra’s final plans were presented in 1928 and, with the architect serving as general contractor, construction occupied most of 1929. In a poetic homage to Sweet’s Catalogue of building supplies, the Lovell House rests on a light steel frame and consists of three stories of steel, concrete, glass, and metal panels. The house epitomizes the ethic and aesthetic of mechanical assemblage, and the frame truly is the essence of the 4,807-square-foot building. The light concrete gunite was shot onto the wire lath by long hoses extending from mixers on the street. Open-web steel floor and ceiling joists harbored plumbing and wiring. Extended balconies and sleeping porches were suspended, not cantilevered, from the perimeter of the roof frame.

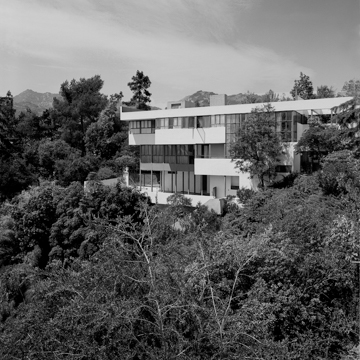

Perched over a canyon in the Hollywood Hills, a terrace moves from the street into a topfloor entry hall, which leads to an informal family room and bedrooms. It also frames and overlooks one of the finest stairways in all modern architecture—the staircase lighting for which Neutra used actual headlights from a Model A Ford. The stairs descend to a long living room that faces southwest and turns north at the corner to the dining room, kitchen, and servants’ quarters. The bottom floor housed utilities and the partially covered swimming pool. Neutra designed most of the simple furniture for the house. Beds, banquettes, desks, and cabinets were generally built-in, though he also conceived freestanding tables and wood and tubular steel chairs. The original dominant colors were white, gray, blue, and black. Carpets and draperies were gray and beige, the metal trim was gray, and most of the painted woodwork was black. The long, handsome living room lighting trough is of polished aluminum, with light reflected upward against white walls and ceilings and filtered downward through translated glass panels.

The architect also supervised the landscaping. Successive layers of low retaining walls followed the contours of the steeply sloping site. Subsequently overcome by rampant foliage, the curving walls furnished a lyrical counterpoint to the orthogonal lines of the house. Purple wisteria covered the constructivist front pergola. Connected to the main house, via terraces, trellises, and garden walls is a large garage wing, with Leah Lovell’s kindergarten rooms underneath. Philip Lovell’s elaborate gymnastic equipment served as outdoor sculpture on the lushly landscaped terraces. Though Lovell would later recall it as being more, the total cost, according to Neutra’s final statement, came to approximately $65,000 (exclusive of land costs).

Upon completion, Neutra and Lovell welcomed the public and conducted personal tours. The residence was featured in the American and international press, and was included in the famous Exhibition #15 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1932. Its inclusion in the show led MoMA curator Arthur Drexler to later insist that the house “became for a while indispensable to the iconology of modern architecture: it was an image of such persuasive authority that it seemed to promise whole chapters of revelation to come.” To complement the rows of industrial casement windows and their metal interstices, Neutra alternated long bands of light concrete that surged beyond the box. It was, Drexler believed, “a beautiful and subtle weaving of line and plane, intuitively balanced and, for all its intricacy, serene.” The Lovell House, he observed, seemed “to be walking, or floating...out of the site. The image was compelling.”

On Neutra’s compositional strategies, Drexler contended that while such Europeans as Mies van der Rohe and Gerrit Rietveld had “translated the Wrightian picturesque into the language of abstract painting…Neutra’s architecture advanced…from the Japanese sources he and Wright both admired.” Drexler saw the Lovell House as an architectural ensemble that offered an impression of spontaneity, but was in fact carefully designed to convey a calm but enlivening atmosphere.

Neutra’s more compact work of the 1930s and 1940s also produced several acknowledged masterpieces, especially the Kaufmann House in Palm Springs (1946). Perhaps even more significantly, he translated the essences of his larger, grander buildings to smaller houses and apartment structures for middle- and lowincome inhabitants, including the Strathmore and Landfair Apartments in the Westwood district of Los Angeles (1937) and the Channel Heights housing project for shipyard workers near Los Angeles’s San Pedro Harbor (1942). Similarly, especially in the 1930s and 1950s, Neutra was particularly effective in his design of schools which, like his houses, took advantage of the Southern California climate for indoor–outdoor interaction. In these ways, his grand structures for wealthy clients like Lovell continued to furnish lessons and models for more modest structures and less privileged users as well.

From the Lovell House to its more modest cousins, Neutra’s work illustrated the essence of all great architecture—a comforting shelter from the world and a stage for confronting and enjoying life. The Lovell House remains privately owned.

References

Drexler, Arthur. “The Architecture of Richard Neutra.” In Architecture of Richard Neutra: From International Style to California Modern, 19-56. Edited by Arthur Drexler and Thomas S. Hines. New York: the Museum of Modern Art, 1982.

Hines, Thomas S. Architecture of the Sun: Los Angeles Modernism, 18701970. New York: Rizzoli Press, 2010.

Hines, Thomas S. Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture. 2nd ed. New York: Rizzoli Press, 2005.

Lovell, Philip. Interview by Thomas S. Hines. Newport Beach, California, February 16, 1973.