You are here

Greater World Earthship Community

Built from earth and old tires, Mike Reynold’s Earthships are radical experiments in sustainable architecture that propose alternative systems for building, living in, and owning a house in our industrial society.

In 1969, Reynolds graduated in architecture from the University of Cincinnati; his thesis project for high-density suburban dwellings questioned contemporary building codes, methods of financing, and property ownership. He moved to Taos, where be bought 20 acres of land. Anchored by the pueblo, Taos had drawn refugees from the modern world since the early twentieth century, and in the early 1970s was undergoing a renaissance as a countercultural mecca.

In 1972, Reynolds erected the Thumb House from beer cans wired together into “bricks.” Between 1976 and 1986, he extrapolated this experiment with recycling into a series of Earthship prototypes at Castle Compound. Reynolds built first Earthship in 1987, and in 1989 founded REACH (Rural Earthship Alternative Community Habitat) on 55 acres of a steep mountain slope near the mouth of Taos Canyon. In 1994, he launched the Greater World Earthship Community on 633 acres of land 14 miles outside Taos, between the Rio Grande Gorge and Route 64.

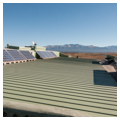

Dug into a south-facing slope or berm, Earthships are typically assembled from U-shaped modules with maximum dimensions of 18 feet wide by 26 feet deep. These can be configured into variously straight, staggered, and stepped plans, depending on the site and program. The walls are constructed from automobile tires packed with earth, which give them a standard thickness of 2 feet 4 inches. Non-load-bearing infill and partition walls are made from aluminum cans or glass bottles set in cement mortar. The walls are finished with two inches of plaster and roofed with such locally available materials as pine beams, but also steel or concrete beams, plywood trusses, or wood joists. Operable skylights provide both interior illumination and ventilation. The roof slopes back toward the berm and has drainage canals that collect and channel rainwater to catchment basins and cisterns at each end of the Earthship. A greenhouse with sloped double-pane glazing runs across the south side of the modules.

Reynolds likens his Earthships to Noah’s Ark: “Just as Noah needed a life supporting ship that would float independently without access to land, we are in need of life supporting ships that will ‘float’…independently without access to various archaic self-destructive systems upon which we have grown dependent… We need to evolve self-sufficient living units that are their own systems.” Grounded in the earth yet floating free from the world’s industrial entropy, Earthships seek to replace the unsustainable practices that enable conventional housing with sustainable systems of materials, power, water and sewage, food, and financing.

As much as possible, Reynolds fabricates Earthships from trash rather than new materials or even recycled materials that have been reprocessed for construction. Trash breaks the wasteful cycle of energy consumption by reusing materials as they are found, thus saving the embodied energy that would otherwise be discarded. Reynolds considers automobile tires to be the primary “indigenous” material among the many “natural” resources of our industrial world.

And as much as possible, Earthships operate off the grid from centralized utilities. The thermal mass of its berm-and-tire construction and its southern orientation work together as a daily “battery” that stores and releases heat without relying on electricity or gas. Limiting the energy load, Earthships function as their own power plant by deploying photovoltaic panels or windmills to generate, and batteries to store, electricity. Earthships also have a water plant, with a distillation system to purify the rainwater collected on the roof. Complementing this system, Earthships have a sewage plant that segregates black from grey water, sending waste to the septic tank while directing grey water to the greenhouse. In theory, if not yet in reliable practice, the septic system could be used to produce methane gas and eliminate the need for tanks of propane for cooking. The greenhouse provides Earthship residents with food.

Finally, as much as possible, Earthships aim to free their owners from the economic mechanisms and institutions of industrial society. According to Reynolds, the Earthship turns the house into a “method for survival” that is “accessible to the common person” because it does not rely on external sources of funding. Circumventing the norms of property ownership, land at the Greater World Earthship Community is held in common. While Reynolds provides construction contracting and crews, he encourages owners to build their own houses, investing their labor instead of borrowing money. As self-sufficient systems, Earthships take utility companies and their bills largely out of the equation.

Inevitably, Reynold’s insistence on working outside the codes of contemporary practice got him into trouble. In November 1997, the Taos County Planning Department issued an injunction halting all construction at the Greater World Earthship Community, claiming that it was in breach of regulations requiring a public infrastructure of roads and utilities, and that the properties had been illegally conveyed. After complaints to the New Mexico State Board of Examiners for Architects, which charged Reynolds with “inappropriate siting, subsurface water accumulation, waste disposal on slopes, and incomplete construction administration,” he relinquished his New Mexico architect’s license in 2000 to avoid being sued for malpractice; he lost his national license that same year (but remained licensed in Colorado and Arizona). Legally forbidden to use the title of architect in New Mexico, he started calling himself a Biotect and changed his company name from Solar Survival Architecture to Biotecture.

In March 2004, the Taos County Commission allowed Reynolds once again to develop the Greater World Earthship Community. But it was now subject to strict rules, including private ownership of individual lots, uniform roads, and standardized house plans. Forced to create what was effectively a conventional subdivision, Reynolds says that he “lost the freedom to fail,” i.e., the ability to experiment that had been crucial to his work since 1972.

Reynolds launched a three-year campaign in New Mexico to secure passage of “The Sustainable Development Testing Site Act.” He seized on the example of Trinity Site, where an experimental and unproven nuclear device was tested in July 1945, to make the case that such field laboratories are essential instruments of technological inquiry and progress. Signed into law in March 2007, House Bill 269 authorized Reynolds to develop his Earthships as experimental test sites without interference from the conventional codes of architectural design, building construction, and community planning. That same year his national architect’s license was reinstated.

Apart from Noah’s Ark, Reynolds identifies no architectural precedents for his Earthship communities. Yet they stem from the same utopian impulse that generated Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses and Broadacre City, Paolo Soleri’s Cosanti and Arconsanti, and Buckminster Fuller’s prescriptions, in his Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, for closing the gap between architecture and industrial technology through an integrated systems approach to the parallel problems of building, transportation, food gathering, and energy harvesting. More distant but just as relevant, Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond is the original American blueprint for Reynolds’ continuing Transcendentalist experiment in balancing the inventions of human technology with the sustainable order of nature.

The visitors’ center at the Greater World Earthship Community is a demonstration Earthship and is open during regularly scheduled hours; tours are also offered.

References

Fuller, R. Buckminster. Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. New York: Pocket Books, 1970.

Hodge, Oliver, Sally Jo Fifer, Lynne Kirby, Mette Hoffman Meyer, Rachel Wexler. Garbage Warrior. Toronto: Morningstar Entertainment, 2008.

Reynolds, Michael. “Residential blanket scheme: rethinking the city’s architecture, and adding to the land.” Architectural Record 152, no. 4 (April 1971): 136-138.

Reynolds, Michael E. Earthship Volume I: How to Build Your Own. Taos: Solar Survival Architecture, 1990.

Reynolds, Michael E. Earthship Volume II: Systems and Components. Taos: Solar Survival Architecture, 1991.

Reynolds, Michael E. Earthship Volume III: Evolution Beyond Economics. Taos: Solar Survival Architecture, 1993.

Sharpe, Thomas. “Controversy Over Green Hero.” Architectural Record 188, no. 6 (June 2000): 36.

Soleri, Paolo. The Bridge Between Matter and Spirit is Matter becoming Spirit. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1973.

Thoreau, Henry David. The Annotated Walden: Walden, or Life in the Woods. 1854. Reprint, New York: C.N. Potter, 1970.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. The Living City. New York: Horizon Press, 1958.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.