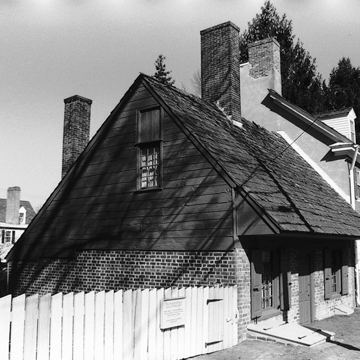

The tiny brick-and-frame house with a steep roof was long thought to date to around 1660, the product of Dutch builders. Historians pointed to, among other things, the very wide overhang of the front eave (with a matched-board soffit below), this being a feature of several Dutch dwellings in America, including the Holmes-Hendrickson House, Monmouth County, New Jersey (mid-eighteenth century). By the early twentieth century, the house's quaintness was irresistible to artists, such as the young painter shown with her easel “in front of a famous Dutch colonial house” in National Geographic (1935). Looking to the town's Tercentenary, Mary Wilson Thompson's Delaware Society for the Preservation of Antiquities bought the place in 1937. The group toyed with calling it the “Old Swedish House.” Kruse restored it, rebuilding the south wall and replacing the floorboards downstairs (using them, it seems, to build the garden fence). He roofed the house with “old moss” asbestos shingles and painted the interior light “Quaker gray,” except the kitchen windows which were colored “Dutch blue.” Louise du Pont Crowninshield furnished the rooms. On opening day, Mrs. Thompson greeted guests in the kitchen, showing the fireplace Kruse had uncovered.

The Dutch House has for decades been operated as a museum by New Castle Historical Society. Their repainting in 2001 of the exterior trim in red, based on paint analysis, caused a stir. Two years later, architectural historian Jeff Klee removed some wall plaster and floorboards in an attempt to resolve the date of the house. He discovered that the building was fashioned with a series of heavy timber frames or “H bents”—sometimes, but not always, a sign of Dutch construction. As with the Ryves Holt House, Lewes (ES18), the house originally had exposed ceiling joists with chamfered edges and lamb's-tongue stops, and wall posts. Between the posts is brick nogging. According to Klee's analysis, the building was originally all-frame, consisting of a single room with a big cooking fireplace on the north wall; later in the eighteenth century the interior was partitioned and the house encased in a brick exterior wall, as one sees today. In the early nineteenth century, the end chimney was replaced with a center one, the roof was raised, and the interior refinished. It seems likely that the present front eave represents a rebuilding of that element higher on the front of the house following the raising of the street level here (one now steps down from the sidewalk into the entry). Why the eave is so wide is unclear, unless it provided storage space. Nothing is indisputably Dutch about the place, and none of the owners' names was ever anything but English. “Not Really So Dutch After All,” read a Wilmington News-Journal newspaper headline reporting the new findings.