You are here

Ogden Goelet House (Ochre Court)

The three-and-one-half-story Ochre Court is somewhat startling in scale as it rises abruptly from the its sparse landscaping. Hunt designed this summer house for New Yorker Ogden Goelet and squeezed it onto a surprisingly narrow parcel of land just across the street from McKim, Mead and White's Shingle Style house of 1882 for Robert Goelet, Ogden's brother (partially visible to the north over the perimeter hedges). As with many other houses along the cliffs, Hunt has incorporated two fully developed facades into his design. The street facade, set a short distance behind a set of extravagant iron gates, is clearly inspired by French château imagery, which this was the first of Hunt's Newport houses to employ. The main section, offset at the south end of the building, is clearly distinguished from the service wing to the north by its more elaborate carved trim and the concentration over the entryway of arched windows and the intricate ornament of a pedimented dormer set against the steep rake of the roof. The limestone walls, set in flush blocks, have broad unarticulated areas,

Ochre Court seems less cramped on its site and more balanced on its ocean side, where Hunt established a handsome cadence of arcaded porch openings and windows across its main block to the left, terminated at either end by towerlike projections. The open loggia on the first story leads out to a broad terrace that clearly sets the house off from its lawn. Through a series of setbacks Hunt has done more to diminish the bulk and blandness of the service wing on this facade than on the street elevation.

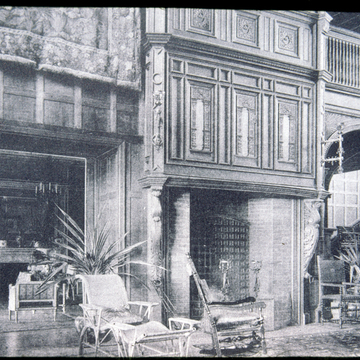

Inside the main entry is a masonry-walled stairwell that immediately opens onto a three-story court. Through the arched openings beyond, the coastal light and salt air dramatically flood into the central space. Surely Hunt and his client were aware that a similar feature existed next door in the Robert Goelet house, albeit on a smaller scale. Here the architect brought his newly developed grand manner to the design, with a palatial scheme of sculptural ornament, carved woodwork, painted ceiling, and open galleries stacked above. If his design does not make it clear enough that Hunt was informed by late medieval sources, he added one more clue. On the garden structure to the right of the main entry, fashioned like a cathedral's rood screen, is a self-portrait by Hunt just below the central pedestal. Here he depicted himself pondering his own work, hand to chin, not unlike the sculptural self-portraiture of the great master architects and builders of the Middle Ages.

Although the house retains its courtly ambience, some of the interior decoration and much of the original artwork have been altered or lost through its present use as the administration building for Salve Regina University. Happily, the university is now more sensitive to its environment, having recently hired Robert A. M. Stern to design the Rodgers Recreational Center (2002), across Ochre Point Avenue from the main gate of Ochre Court. In this rare (for Newport) postmodern effort, contextualist Stern humanized the awkwardly functional gymnasium mass by employing a full range of Shingle Style elements—engaged towers, multiple cross gables, undercut arches, trellis work, and even patterning in the shingles themselves. He sited the entrance on axis with the broad arch of Peabody and Stearns's recently restored shingled fantasy, the Hennery (1883), which separates the new recreation center from the Hunt building.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.