More than the Market House, the First Baptist Church architecturally marked Providence's growing importance. In 1638 Roger Williams founded the first Baptist church in America. For sixty years before the erection of a meeting house it met in the parlors of members of the congregation. By the early 1770s a new building was needed, and it was conceived in a very large way. Built to accommodate 1,400 people (when the population of Providence stood at 4,300), it was intended both “for the publick Worship of Almighty God; and also for holding Commencement in.” The commencement referred to was that of Rhode Island College (later Brown University), also founded under Baptist auspices. It had just been weaned away from Warren, Rhode Island, the place of its founding, largely by Brown family persuasion. The church that resulted from its avowed goal of combined benefit to town and gown is among the grandest built in the colonies, although not without a degree of provincialism in design.

Joseph Brown, the amateur architect, went to Boston, together with the master carpenter Jonathan Hammond, in search of ideas. In the end, however, most of these derived from several plates illustrating Sir Christopher Wren's London churches in James Gibbs's Book of Architecture (1728), a copy of which Brown had in his architecture library. Yet the result is especially interesting because Brown filtered the typical Anglican church schemes of Wren through what was then becoming an

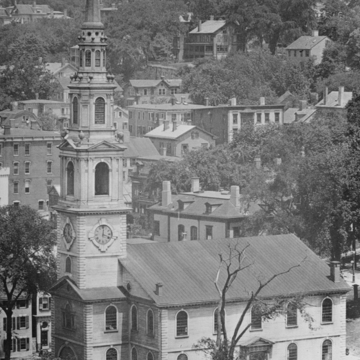

If any skyline feature gave special identity to the meeting house (and often none did), then the favored sign was a cupola. By substituting for the meeting house cupola a spired tower over the entrance end toward North Main Street, Brown further accentuated the churchly character of his design. So the First Baptist Church stands on the cusp of change: the old meeting house tradition fading with the emergence to dominance of the longitudinal church type even in situations where the older type had previously reigned.

As further indication of its transitional status, this church shows a sumptuous front grafted onto a plainer body, with the two aspects a bit unintegrated. From a plate in Gibbs which displayed three alternate designs for his own St. Martin-in-the-Fields on Trafalgar Square (1726), Brown (probably in consultation with the congregation's building committee) selected one of the rejected designs. They called on a carpenter from Boston, James Sumner, to handle this feature, which only barely interlocks with the body of the church. A square, quoined base with a clock is successively topped by a belfry with arched opening framed by paired Ionic pilasters and pedimented in four directions, then by two superimposed polygonal lanterns with paired Corinthian pilasters at the corners, all telescoped on the spire, with progressively smaller urns set on the ledging at each of the stages. Whereas the designs for St. Martin were made for a full temple front, the one-story porch flanked by paired Doric columns for the First Baptist Church came from another plate for a lesser church by Gibbs, Marylebone Chapel, with a much smaller tower, which Gibbs also illustrated.

A steep interior double stair folds within the base of the tower to bring the worshiper from North Main Street up to the level of the meeting hall. Simple hung plaster vaulting shapes the interior space, elliptical across the nave, groined over the aisles, in a visual and technical simplification of Marylebone's vaulting. Around three sides, balconies are supported midway by the giant Tuscan columns which separate nave from aisles. A double tier of round-arched windows lights each level. Although somewhat summarily wrought, the entablature cappings of the columns make a forceful visual presence, spreading as generous tables to receive the plaster vaulting.

Up front, the exquisite array of architectural elements against the plaster wall behind the raised pulpit recalls the layout of engraved models in architectural pattern books in Brown's collection. The crystal chandelier, imported from Britain (probably Waterford), was given to the church in 1791 by Hope Brown in memory of her father, Nicholas, and was first lighted on the occasion of her marriage to Thomas Poynton Ives. Changes occurred through time. In 1832 the original high box pews were removed for the present replacements (which, however, have doors to make them appear boxed). With this change, the aisle across the center of the church also disappeared; so, for a while, did the original high pulpit and its sounding board. In 1834 Nicholas Brown II donated the organ, which retains its original case and, despite two rebuildings, some of its original pipes. Finally, in 1884, the front went through a radical change. The baptismal pool was given more focus by placing it within a niche cut into the pulpit wall and backed by a stained glass image of St. John the Baptist. Then, in 1957, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a graduate of Brown and a noted Baptist, provided for a near-complete restoration of the Mother Church of the American Baptist denomination. This restoration walled in the baptismal niche, recreated the high pulpit and its sounding board, and replicated the original Palladian window behind the pulpit as a

With two exceptions (1804 and 1832), Brown undergraduates have marched down the hill for commencement in the First Baptist Church every year since 1776—except that, as the university has grown, it is now an undergraduate baccalaureate ceremony that takes place in the church preceding commencement uphill on the Green. Of all eighteenth-century Rhode Island colonial churches, this and Trinity Episcopal Church in Newport ( NE56) stand among the major ecclesiastical buildings of the period—Trinity toward the beginning of the eighteenth century, this at the threshold of independence.