You are here

Blount Mansion

Located in downtown Knoxville overlooking the Tennessee River, the house was constructed from 1792 to 1830 for William Blount, a signer of the U.S. Constitution and a U.S. Senator. The Federal-style dwelling served as the capitol of the Southwest Territory from 1792 to 1796, and the home of the Blount family and their slaves until 1824. Much of the Tennessee Constitution was drafted here in 1796. State historian John Trotwood Moore once called Blount Mansion “the most important historical spot in Tennessee.”

A native of eastern North Carolina, William Blount (1749–1800) was a member of a prominent family of merchants and planters. During the American Revolution, he was a paymaster responsible for recruiting and re-equipping military forces under General George Washington. In the 1780s, he served several elected positions, including a member of the North Carolina House of Commons and State Senate. Blount was a delegate to the Congress of the United States in 1782–1783 and 1786–1787. More importantly, he was a member of the 1787 Convention that framed the U.S. Constitution, which he signed and later voted to ratify in 1789. Blount was also a land speculator who purchased thousands of acres of military land grants on the western North Carolina frontier.

In 1790, President George Washington appointed his former comrade-in-arms as governor of the Territory of the United States South of the River Ohio, commonly called the “Southwest Territory.” With this position, Blount was also made the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Department. While holding this dual office, Blount relocated first to William Cobb’s home at Rocky Mount near present-day Johnson City, Tennessee, then in early 1792 to the frontier village of Knoxville, which he had helped found the previous year. During this time, he skillfully organized the territorial militia and led negotiations between the federal government and the powerful American Indian tribes of the southern frontier: Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws.

Governor Blount presided over the Constitutional Convention that met in Knoxville in January 1796 to transform part of the Southwest Territory into the State of Tennessee. Subsequently, Blount was elected by the new state legislature to represent Tennessee in the U.S. Senate, which then met in Philadelphia. After a political controversy resulted in his expulsion from the U.S. Senate, Blount returned to Knoxville and in 1798 he was elected speaker of the State Senate.

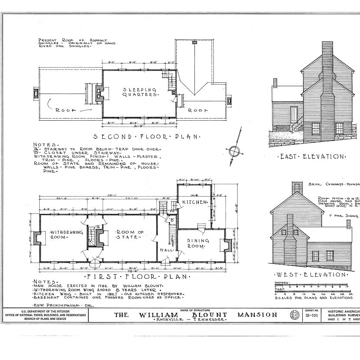

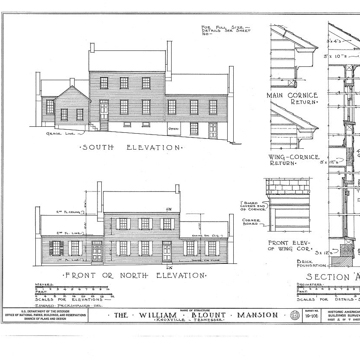

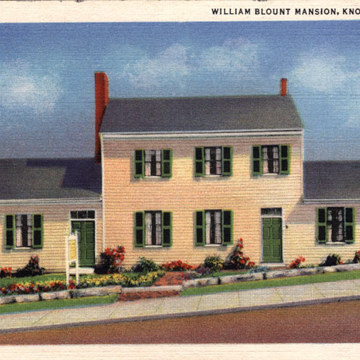

Constructed in four distinct phases between 1792 and 1830, the central section of Blount’s timber-frame house was constructed in 1792–1795, initially as a one-story house with an attic sleeping loft. The one-story west wing was originally a dependency, likely housing slave quarters, that was connected to the main block around 1810. By 1825, the house had been enlarged with a second floor on the central section and by 1830 with the addition of a one-story east wing, giving the house its current form. Covered with unifying weatherboards, the Federal house features a side-gabled wood shingle roof, three brick chimneys, six-over-six and six-over-nine double-hung windows, and a limestone and brick foundation with a partial basement.

The house has hall-parlor plan, a quarter-turn stair, paneled entrance doors with transoms, simple mantels, and paneled wainscoting. Many of the original construction materials, such as nails and window glass, were shipped to Tennessee from North Carolina and Virginia. When compared to the rough frontier-era log buildings that surrounded it, Blount’s house was considered a “mansion.” Local Native Americans called it the “House with Many Glass Eyes” because of its numerous windows.

William Blount lived here with his wife Mary Grainger Blount (1761–1802), six children, and ten enslaved African Americans. Andrew Jackson and John Sevier were frequent guests, and early visitors included botanist André Michaux, the future King Louis Philippe of France, and various Cherokee Indian chiefs. William Blount died here in 1800, his wife in 1802. Blount and Grainger counties, Maryville, and Blount College, which evolved into the University of Tennessee, were named in their honor.

From 1800 to 1824, the home was owned by four members of the Blount family, including William Blount’s half-brother Willie Blount (1768–1835), who served as governor of Tennessee from 1809 to 1815, and his son William Grainger Blount (1784–1827), who served as a U.S. Representative from 1815 to 1819. During Knoxville’s tenure as the state capitol (1796–1812), the house served as the governor’s residence, from 1809 to 1812. After 1824, the home had several owners, including Knoxville mayors Matthew Gaines and Samuel Boyd. In the 1910s, the dwelling was converted into a boarding house for immigrant workers.

In 1925, when it became public that the city might demolish the house to make way for a hotel parking lot, a local group of preservationists led by Mary Boyce Temple (1856–1929) formed the Blount Mansion Association (BMA) and raised $31,500 to purchase the run-down property. In one of the earliest historic preservation projects in Tennessee, the BMA restored the mansion, its outbuildings, and grounds for use as a historic house museum, which opened to the public in 1930. Non-original Victorian-era porches and additions were removed at this time.

To the rear of the house is the original one-story office building where William Blount governed and conducted business affairs, an original brick “cooling shed” for storing food and wine, a detached slave kitchen that was reconstructed in 1960, and restored formal terraced gardens. The BMA also owns and maintains the adjacent Craighead-Jackson House, an 1818 Federal-style brick house across the street to the east. Since the 1950s, the BMA has utilized the latest advances in preservation technology and archaeology to restore, maintain, and interpret the William Blount Mansion property; a modern visitors’ center opened in 1996. Today, the William Blount Mansion, the city’s oldest museum and the birthplace of the State of Tennessee, is Knoxville’s only National Historic Landmark.

References

Emrick, Michael, and George T. Fore. “Blount Mansion: Architectural Analysis and Reinterpretation of a Tennessee Landmark.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly55, no. 4 (Winter 1996): 310-319.

Hamby, Brooke. “An Archaeological and Historical Investigation of the Blount Mansion Slave Quarters.” Master's thesis, University of Tennessee, 1999.

McMurry, Ben J. “Blount Mansion,” Knox County, Tennessee. Historic American Buildings Survey Documentation, 1934-1936. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, HABS 19-101.

Mielnik, Tara Mitchell. “Blount Mansion.” Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Version 2.0, Online Edition. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 2000–2018. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/.

Retting, Polly M., and Horace J. Sheeley. “William Blount Mansion,” Knox County, Tennessee. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1975. National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C.

Weeks, Terry. “William Blount.” Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Version 2.0, Online Edition. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 2000–2018. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.