The architecture of Bennington College is an interesting mix of Vermont conservatism and progressivism. It embodies reminders of agricultural Bennington, the great late-nineteenth-century Bennington estates, the early-twentieth-century enthusiasm for Colonial Revival, and the special combination of arts and liberal learning that gave rise to numerous small colleges throughout the state in the twentieth century.

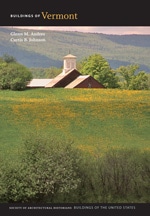

The land on which the college sits was assembled from modest farmsteads in the 1860s by Trenor W. Park, who built a house here in 1885. His daughter Lila and her husband, Frederick Jennings, a New York investment attorney and son of Isaac Jennings, pastor of Bennington's Old First Church, replaced Park's house in 1903 with a stone summer house called Fairview and built an extensive set of agricultural buildings. In 1930 Lila Jennings offered one hundred and forty acres of the estate to community leaders, Reverend Vincent Ravi-Booth of Old First Church among them, who sought to establish a progressive women's college in the town (the college became coeducational in 1969). Though Ravi-Booth had originally sought a site in Old Bennington, Jennings's offer, which included a barn complex, was too good to refuse. Because of the Great Depression, the fledgling school lacked an endowment but gifts from the Jennings and McCullough families enabled the college to convert the agricultural buildings for educational use between 1932 and 1937. The “college in a barn” was soon supplemented with a Colonial Revival quadrangle by the Boston firm of Ames and Dodge, faculty housing (some of it designed by Bennington students), and landscaping that included lawns, open meadows, and vistas designed by Martha Brookes Hutcheson. In 1939 Lila Jennings donated Fairview itself (1903, Renwick, Aspinwall and Owen) and an additional two hundred acres to bring the campus to its full size. Thomas P. Brockway in Bennington College: In the Beginning (1981) notes that in a lecture given by Frank Lloyd Wright at the college in the mid-1930s, he de-cried the Colonial Revival core of the college as unsuitable for a modern school. Indeed, the school's progressive aspirations were perhaps better embodied by the modestly scaled modernist buildings designed by Pietro Belluschi (BE17.2), Edward Larrabee Barnes (see BE17.3), and others beginning in the 1950s. The building clusters are arranged to the west of College Drive, which runs from a main gate at VT 67A through to a second gate (now closed) that opens onto Prospect Street.