The first county organized in Vermont, in February 1779, Bennington consists of seventeen towns in the southwest corner of the state, bordering Massachusetts and New York. The towns near the New York border encompass from north to south the drainages of the Batten Kill, Walloomsac, and Hoosic rivers. More than half of the county's land area is in the Green Mountains and is sparsely populated. Its primary villages are Bennington, with a population of about 15,000, in the broad Walloomsac Valley and Manchester, with a population of about 3,800, in the Batten Kill Valley. These villages also serve as “half-shires,” alternating the seat of county government, an arrangement unique in the state.

The county boasts the earliest continuous European settlement in Vermont, with the Town of Bennington organized and settled in 1761. As a focus of the Land Grants Controversy between New Hampshire and New York, the Burgoyne Campaign, and the founding of Vermont in 1777, the county contains some of the state's earliest buildings, though many have been subject to subsequent Colonial Revival remodelings, especially in the twentieth century.

By 1791, the county had more than 12,000 residents. Early industry included a blast furnace and ironworks in Bennington, a furnace and the state's first marble quarry in Dorset, and the Eagle Square Tool manufactory, which joined water-powered mills along Paran Creek on the Bennington-Shaftsbury town line. By 1810, a checkerboard of farms covered the rolling landscape from Pownal to Shaftsbury in what were some of the most populated towns in the state. A ride along the post road (now VT 7A) passed at about every six miles a designated village center. These were centrally located within each town, as envisioned by the towns' New Hampshire Grant charters. Farther north the road crossed over to the narrow Batten Kill Valley in Arlington and Manchester where farms developed their boundaries based more on the river than the road. Prosperous farms and industrial villages soon led to a flowering of the building arts, initiated by the work of master builder Lavius Fillmore and other carpenters. As villages matured during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, they erected Greek Revival commercial landmarks, such as the Equinox House stagecoach hotel (BE6) in Manchester and Powers Market (BE16) in North Bennington. Most mountain towns reached their peak agricultural settlement just before the Civil War, looking east to the Connecticut River and south to Massachusetts for their architectural models.

The Western Vermont Railroad, constructed from Bennington to Rutland in 1852, brought access to the western portion of the county, reinvigorating manufacturing in Bennington and North Bennington and enabling large-scale marble quarrying in East Dorset. Textile manufacturing joined potteries and machine shops in Bennington village to reshape it as the regional leader in manufactures. Its downtown became the county's preeminent commercial center, with four blocks of three-and four-story buildings. The Bennington Depot (1897–1898) at 150 Depot Street, designed by local architect William C. Bull, along with many fine houses rival their contemporaries anywhere in the state.

Between 1887 and 1892, the county reached its peak population of more than 21,000 residents. This period saw the erection of the Battle Monument (BE23) and the incorporation of Old Bennington as a separate village. The Colonial Revival style became popular, drawing on older local buildings as inspiration and many as a canvas. Old Bennington, Manchester, Arlington, and Dorset villages attracted summer residents interested in buying a colonial country house. Manchester village in particular blossomed as a summer resort at the end of the century, in part through the prestigious patronage of Robert Todd Lincoln at Hildene (BE8). The timber harvest of the Green Mountains peaked during these years and found its way to the mills, manu-factories, and rail yards of Manchester, East Arlington, Readsboro, and Wilmington. In mountain towns many farms were abandoned and populations plummeted, but agriculture remained vigorous in the western towns, in part supported by the estates and show farms of wealthy and often seasonal residents such as the families of Edward Everett and James Colgate.

Colonial Revival remained the defining cultural theme for much of the county well into the twentieth century. However, after World War II Bennington's industries sputtered, the resorts lost favor, farming declined in the valleys, and the Green Mountain National Forest acquired much of the abandoned and cutover mountain towns. The county struggled through the 1960s but saw its fortunes rise with development of the southern Vermont ski industry and an influx of exurban migrants. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, the most striking growth was redevelopment of the historic Manchester resort and Manchester Center's emergence as the upscale retail outlet capital of Vermont.

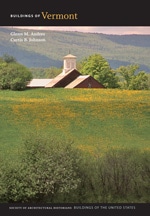

Although, historically, Bennington County is the home of the Green Mountain Boys, architecturally it shares much of its vernacular building traditions with its neighbors in New York and northwest Massachusetts, and this makes the county distinct in the state. From Federal and Greek Revival masterworks and stone mills to elaborate Victorian houses and commercial buildings, Old Bennington, downtown Bennington, and North Bennington display a range of high-quality buildings comparable only to Burlington within Vermont. More subtle and less recognized are some well-preserved nineteenth-century agricultural landscapes, tucked away in the rolling hills of Pownal, western Shaftsbury, and the Batten Kill Valley. Traveling the old post road (VT 7A) leads one through the linear rural villages of Shaftsbury and Arlington and to the northern shire of Manchester and its many landmarks. On VT 30, lovely Dorset, with its long narrow green, remains very much a former stagecoach village that has slowly developed into a haven of distinguished summer residents and preservationists. And for better or worse, in places like Manchester, with its expanding retail development and new “trophy” houses, a contemporary Bennington County vernacular, part Colonial Revival, part Postmodern, has emerged.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.