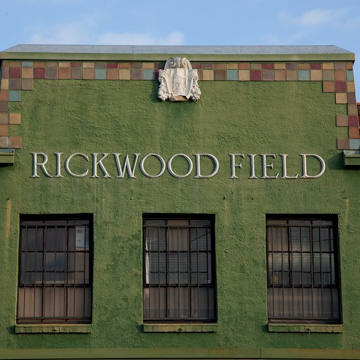

Unless specifically searching for it, no one would expect to find a classic, functioning baseball park among Birmingham’s western neighborhoods. Yet here stands Rickwood Park as it has since it was created in 1910. Rickwood is not monumental in a structural or architectural sense, though it is a significant monument in a figurative way. Here, Allen Harvey (“Rick”) Woodward, scion of the family that had developed Birmingham’s Woodward Iron Company, created for the city a social space that was not devoted simply to the industrial work environment, nor to the classic institutions that usually distracted the community’s attention from that environment, such as churches, theaters, or libraries. Rather, Woodward created a sports venue.

Rickwood Baseball Field was, furthermore, an early if halting attempt to accommodate the racial divisions that plagued Birmingham and all of Alabama. It was also a monument to civic ambitions in a quickly emerging industrial municipality that planned to rival and, it hoped, be the leader among the already established cities of the “New South,” such as Atlanta. And, of course, Rickwood is also a monument to the American craze for baseball that gripped all parts of early-twentieth-century America. Today it stands as the oldest baseball park in the country that still remains both on its original site and within its original structure.

In 1909, Rick Woodward purchased the local baseball team, sometimes known as the Coal Barons but more properly as the Birmingham Barons. Shortly thereafter, he purchased a 13.5 acre plot on the edge of the city from the Alabama Central Railroad Company. It was an area of middle- and working-class suburbs that was developing in proximity to the steel mills of Ensley and Fairfield, an area not then densely populated though served by streetcar lines from Birmingham’s urban core. Within a year of his purchase, Woodward had built and opened Rickwood, the baseball park he named for himself, as the home field for the Birmingham Barons. Significantly, in an era of Jim Crow segregation, shortly thereafter it also became the home field for the Birmingham Black Barons.

The design for the park is said to have been chosen by Woodward and the architects he consulted during a tour of northern ball parks. Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field was selected as the model, and Woodward hired its builder, the General Fireproofing Company. The firm, in fact, created a Birmingham subsidiary, the Southeastern Engineering Company, to design and construct Rickwood Field. As originally built, Rickwood comprised a covered symmetrical grandstand that extended from the first-base dugout to the third-base dugout, with uncovered concrete bleachers on steel supports reaching from the grandstand to each side down the right and left field lines. A concrete entryway to the park, in a vaguely Mission style with tile roof, was added in 1920. There were other additions and improvements to the grandstand and bleachers later in that decade, including separate wooden bleachers along the right field for African American fans.

It is easier to plumb the physical characteristics and history of Rickwood Field than to read the intentions of Rick Woodard in creating and building it. His interest in baseball in particular from childhood through college years at Sewanee can be documented in his own words. But his appreciation of baseball’s connection with urbanization, with benefits in industrial workplaces, with social stratification, and particularly with the rise of Birmingham as a major industrial hub, while suggestive, can only be speculative. Unlike some other businessmen, Woodward is not known as a proponent of the view that characteristics of baseball reinforced in players and fans alike traits useful in the industrial workplace—like skillfulness, efficiency, teamwork, division of labor, and respect for authority. Still, Woodward’s notions of useful connections between industrial production and sport may be inferred from his other contribution to Birmingham’s athletic scene: the Woodward Golf and Country Club for employees of the Woodward Iron Company. What can be documented is that in the early years of Rickwood Field, under Woodward’s guidance, attendance grew steadily, patronage included a range of social classes, and both public and press avidly followed the results of games played there as well as the athletic feats of star players. Parallel with these developments, the facility was steadily improved, seating was expanded in the 1920s, lighting was added in 1936, and local industries patronized outfield billboard advertising.

Although historians record that the ball park became a popular gathering place for Birmingham residents of every sort, this did not mean that they all gathered together. Perhaps the most obvious social stratification identified at Rickwood is in seating patterns. Apart from racially segregated seating, some inferences can be drawn from configuration of the principal seating facilities: elite patrons watched the games in box seats directly behind home plate, where they were provided with individual wooden chairs, said to have originally been used at New York’s Polo Grounds and grandly advertised as “opera seating.” Behind the boxes was grandstand seating for less economically privileged fans, and bleacher seats extending outward from the grandstand along the base lines were the cheapest seats. The far section of wooden bleachers beyond right field was reserved for black patrons when white teams were playing and white patrons when the Black Barons played.

Opportunities to make money at Rickwood arose not just from baseball. Football games were also played on Rickwood Field, usually when either Auburn (then Alabama Polytechnic Institute or A.P.I.) or the University of Alabama met their rivals on its turf. The field was once rented to the Alabama Ku Klux Klan, headquartered in nearby Tuscaloosa, for the initiation of new members (though Woodward himself had no known affiliation with the Klan). An event for the Catholic Church was even held at Rickwood.

Over time, however, interest in baseball shifted toward major league teams playing in large stadiums in larger cities. Even minor league teams associated with middle-size cities developed facilities larger and grander than Rickwood Field. In part, the decline of baseball, especially in Birmingham as elsewhere in the South, can be attributed to racial integration both in the sport itself and in the city. The Birmingham Black Barons last played at Rickwood in 1960, and the Barons in 1961. Title to the park was transferred in 1966 from a group of businessmen to the City of Birmingham, which leased it to various parties including the Board of Education. In 1992, a private organization, the Friends of Rickwood, was organized to preserve the stadium. It currently holds a 99-year lease from the City to manage and operate the park.

Rickwood’s role today is to memorialize the early development of a great American pastime and to provide a nostalgic setting for ball games among amateur and high school teams, and for reunions of former teammates. For historians, it is also an artifact of early baseball history. While the park is now surrounded by greater Birmingham rather than located on its outskirts, the immediate neighborhood appears less crowded than in past years; some spaces around it are more open and available for automobile parking. The major efforts of the Friends of Rickwood are focused on preservation and maintenance of the building and a collection of artifacts associated with the park and its team. Each season, the Birmingham Barons return to Rickwood Field from their present location at Regions Field to play a commemorative game.

At the urging of its first Executive Director, Chris Fullerton, the Friends of Rickwood also spearheaded replication of a lost feature from the stadium’s past. This was the original press box, a key element in the early days of sports broadcasting and sports writing. Rickwood’s press box was a rather primitive, gazebo-like structure perched on top of the grandstand roof and “barely capable of holding a quartet of furiously scribbling baseball scribes,” as one pundit noted. Its tile roof matched the tile on the entryway added in 1928, suggesting that the press box dated from the same time. Reconstructed seventy years later, in 1998, it was named the “Fullerton Gazebo” in honor of its most fervent advocate.

Although press facilities are now located beneath the grandstand roof rather than the replicated press box, the restored Rickwood Field today reveals the same configuration as seen in historic photographs.

References

Barra, Allen. Rickwood Field: A Century in America’s Oldest Ballpark.New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2010.

Fullerton, Christopher D. Every Other Sunday: The Story of the Birmingham Black Barons.Birmingham, AL: R. Boozer Press, 1999.

“Rickwood Field,” Jefferson County, Alabama. Historic American Buildings Survey, 1993. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS AL-897).

Whitt, Timothy. Bases Loaded with History: The Story of Rickwood Field, America’s Oldest Baseball Park. Birmingham, AL: R. Boozer Press, 1995.