Located on a corner lot in a residential neighborhood in Santa Monica, the home of well-known American architect Frank Gehry is a Postmodern reconfiguration of an early-twentieth-century bungalow that has become a pilgrimage site for students of architecture and a bane to his aesthetically conservative neighbors.

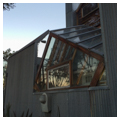

In 1977, Gehry and his wife, Berta, purchased an unprepossessing, two-story Dutch Colonial built circa 1920 on the edge of the Wilmont neighborhood (north of Wilshire Boulevard and south of Montana Avenue). The house’s gambrel-roofed form was peculiar on a gridded streetscape characterized by Craftsman bungalows and low-slung Mediterranean Revival houses. The following year, Gehry remodeled and expanded the house in a manner that virtually exploded it, working with his architectural practice’s young project designer, Paul Lubowicki. First, the two gutted the existing interior, stripping the walls back to their structural, two-by-four stud frame and exposing the rafter system. Then they added to the house’s footprint (mostly on the facade and the north elevation) by wrapping the exterior in a metal shell, creating inhabitable space on the perimeter of the original floorplan. The skin, adhered to wood framing, is composed of mundane materials not traditionally used in high architecture, such as corrugated steel, plywood, and chain-link fencing—materials you might find at a construction site or at a hardware store, such as the one Gehry’s grandparents owned. The manner in which the skin is affixed leaves the older house form visible and mostly intact yet drastically altered. The new spaces are composed of angular, varied, protruding masses arranged in expressionistic ways: glass cubes set on their corners create light-filled, conservatory-like spaces interspersed with solids sheathed in corrugated sheet metal.

The resultant aesthetic was of an ad hoc work in progress, like a sketch. Of the house, architect Paul Heyer said it “is rather a collision of parts, built to stay but with a deliberately unfinished, ordinary builderlike sensibility of parts.” Seemingly reminiscent of early-twentieth-century European avant-garde art movements (specifically Cubism, German Expressionism, and Russian Constructivism), the overall result has been likened by Heyer to Robert Rauschenberg’s ripped cardboard collages of the 1970s (an association further underscored by Gehry’s own line of furniture, “Easy Edges,” designed in corrugated cardboard). In interviews, Gehry stated that he found the incomplete qualities in the paintings of Jackson Pollack, Willem de Kooning, and Paul Cézanne fascinating, and that works in progress were more compelling than those finished. Others have traced Gehry’s influences to the California funk art movement in the 1960s and 1970s, which featured found objects arranged in an unexpected way that ultimately elevated the quotidian detritus to the status of high art. For instance, Gehry’s use of chain-link fencing as a building material was novel: critic Paul Goldberger has said that Gehry’s “goal was not to provoke irritation but recognition that chain link is a ubiquitous material, and that most people don’t think about it or even notice it until the context in which it is seen has changed.”

Gehry’s remodeling of a standard suburban house type using unusual materials and forms is thought, by some critics, to be an early example of Deconstructivism in architectural design. Deconstructivism as a design methodology is predicated upon the disassembly and negation of traditional, historical building models and especially the rejection of the functionality and minimalism characteristic of twentieth-century modernism. As an extremely formalist approach, Deconstructivism can be interpreted as an application of the literary philosophy upon the built world; in other words, practitioners believe that architecture is a communicative language composed of signifiers, which are given meaning by the forms’ (solids and voids) interaction with and disposition vis-à-vis one another. In the case of the Gehry Residence, the owner-architect wished to negate the associative meanings of a middle-class, suburban domicile.

Regardless of his intent, Gehry’s design did irritate the neighbors, who saw the unconventional house as an eyesore. Between 1991 and 1992, Gehry expanded the house a second time, converting the garage into a guesthouse, adding a lap pool, and either removing or cladding much of the addition’s exposed wood framing. Critics balked at the latter change, claiming the infamously crude skin was refined, made to appear finished, and thus shifting the whole aesthetic intention. In 2012, the iconoclastic Gehry Residence received the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA) 25 Year Award for design excellence. The house remains privately owned by the Gehry family.

References

Goldberger, Paul. Building Art: the Life and Work of Frank Gehry. New York: Knopf, 2015.

Hartoonian, Gevork. Architecture and Spectacle: A Critique. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Heyer, Paul. American Architecture: Ideas and Ideologies in the Late Twentieth Century. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993.

Hoyt, Alex. “Frank Gehry’s House: the Making of the World’s Most Famous – and Most Misunderstood – Bungalow, as Fondly Remembered by Frank Gehry’s Project Designer.” Architect Magazine, May 17, 2012.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art Education Department. “Gehry Residence, 1977-78, 1991-92.” Evenings for Educators Series, 2015-2016. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2015.