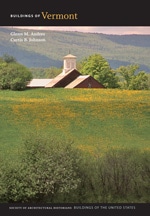

The picturesquely irregular Middlebury village reflects its roles as county seat, early industrial center, market town, turnpike hub, and home to a distinguished college. A variety of genres and broad range of architectural styles mark the village as one of Vermont's most comprehensive and best-preserved centers. Its modest scale belies its significance as a place shaped by a long and vital history.

Middlebury's Hampshire Grant charter, obtained in 1761 by proprietors from Salisbury, Connecticut, specified a centrally located village, but, as with many of the grants, when settlement took off in the 1780s, it concentrated near sources of waterpower. Middlebury Falls on Otter Creek in the northwest corner of the township provided a reliable energy source for saw- and gristmills that served regional needs and subsequently for cotton and woolen mills and an early marble mill (1802). A fording spot above the falls was superseded by the first Main Street bridge in 1787, and this rapidly became the focus of radiating local roads and town-sponsored turnpikes that assured commercial vitality. The turnpikes served as stagecoach routes: Center Turn-pike (Court Street) of 1799 to Boston, Waltham Turnpike (Seymour Street) of 1804 to Montreal, and Troy Turnpike (S. Main Street) of 1811 to Troy and Albany. These turnpikes converged on donated greens at both ends of the bridge, with the larger green becoming the focus of the village and, after 1792, the seat of county government that, in turn, served as a magnet for professional settlement. Equally important for village growth was Middlebury's prominence in education. The county grammar school was established in 1797, its women's counterpart (the first in the state) in 1800, the originally male Middlebury College in 1800, and, in 1814, Emma Willard's female seminary, the first institution of higher education for women in the United States.

Centered on the mill lot of one of the town's founders, Gamaliel Painter, the village grew rapidly from a log-cabin community in the early 1790s to what appeared to Timothy Dwight of Yale upon a visit in 1810 to be “one of the most prosperous towns in New England,” as recorded in Travels in New England and New York (1823). High-quality construction accompanied all phases of Middlebury's history, giving deliberate shape to the community. Over time the town gave visual coherence to its irregular street plan by terminating nearly every vista with a landmark building. Work from three periods stands out in particular: the industrial boom of the early nineteenth century, the civic boosterism that followed the Civil War, and the twentieth-century growth of Middlebury College.

By the first decade of the nineteenth century, Middlebury boasted a sizable population of journeyman joiners, a bookseller advertising builders' guides by Asher Benjamin and Owen Biddle, and the prominent presence of Federal-style joiner-architect Lavius Fillmore. Brought from Bennington in 1805 by Painter to construct the Congregational Church, Fillmore purchased local mills and remained in town for the next four decades. Though documentation of his work on specific projects is rare, Fillmore's influence is tantalizingly evident in building design and in windows and detailing from his joiner's shop. It did much to shape the building boom that accompanied Middlebury's becoming the largest municipality in Vermont for a brief period in the 1830s. Today, that influence survives in an important collection of Federal buildings—domestic, religious, and commercial.

Despite a mid-nineteenth-century decline in manufacturing, Middlebury's position as county seat and agricultural service center generated enough wealth to foster a second building boom in the decades that followed the Civil War. This was largely civic and commercial construction. Some of this work was precipitated by a series of devastating fires on Main Street. Much of it was commissioned by a handful of boosterish local businessmen intent on competing with Burlington and Rutland. Most of it was the work of local architect–builder–mill owner Clinton G. Smith. Drawing upon builders' guides and on visits to architecture offices in major northeastern cities, Smith was adept at a full range of late-nineteenth-century vocabularies. Utilizing details fabricated in his Middlebury mill, he filled west-central Vermont with more than one hundred distinctive urban and rural buildings between 1870 and 1892, when he was called to Washington, D.C., to serve as chief of construction for the War Department. A representative cross section of his work—houses, stores, courthouse, town hall, and churches—can be found around the core of the village.

Middlebury also contains important twentieth-century buildings that result from the patronage of Middlebury College (AD30). As the college expanded its campus beyond an original trio of stone buildings designed in the nineteenth century by local builders, it turned to significant Boston and New York firms for buildings that reflected mainstream taste, the resulting stylistic variety tempered by the parameters of campus materials, scale, and organization.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.