Alabama’s grandest movie palace was designed to be the flagship of the Paramount Publix Corporation’s theater chain in the Southeast. Its Chicago-based architects, Anker S. Graven and Arthur Guy Mayger, had trained in the office of well-known theater design firm Rapp and Rapp.

The theater is eclectic in design with Spanish Renaissance and Baroque influences, and many Moorish details. On the exterior, the primary street facade of brown brick and terra-cotta rises the equivalent of some six stories, centering on a monumental arch with terra-cotta detailing. Slender spiral columns punctuate the arch, with terra-cotta shields, griffins, classical moldings, and other applied ornament further enriching the surface. Diamond-patterned brick diaper work flanks the arch.

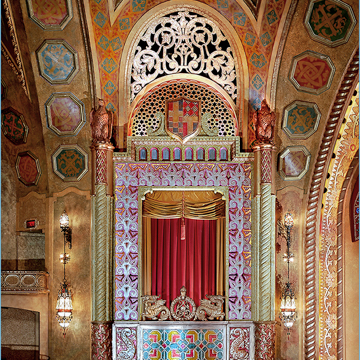

Beyond its architecture, the bright lights of the Alabama’s marquee and sixty-foot-tall sign, spelling out its name to attract patrons from blocks away, give added vitality to what originally was a lively retail and entertainment district. At the entrance begins a procession to the interior that creates a memorable experience even before the show begins. The gilded ticket booth is tucked under a low, brightly lighted, mirrored ceiling that propels one forward to a two-story anteroom sparkling with exotic light fixtures, gleaming marble, and tall mirrors set in multifoil arched openings above a staircase to the mezzanine. Continuing straight ahead, the ceiling drops again to compress a short passage before the main lobby opens up, dazzling in its height and decorative splendor. It beckons the visitor toward a grand staircase that sweeps upward, with glimpses of still other stairs going up and coming down from points unseen, or to the right, on the main level, through ornamental gates and curtained doors to the ornate auditorium.

At first glance, the lavish interiors overwhelm the eye, with richly painted patterns, deeply molded and gilded plasterwork, elaborate light fixtures of clear and colored glass, and wrought-iron with geometric patterns that suggest both classical roots and contemporary tastes in the 1920s. A careful restoration in 1998 brought faded and damaged paint back to life. With an auditorium that contains a mezzanine and upper and lower balconies above the main floor, the theater originally seated 2,500 patrons. A 1972 upgrade reduced that number to about 2,250 seats; and subsequent modernization and ADA compliance has resulted in a current seating capacity of 2,173. Lounges have their own architectural character: Adamesque and Chinese tearoom lounges for women; Tudor style and a hunting lodge theme for men.

The theater retains its original Mighty Wurlitzer organ, a Wurlitzer Opus 1783 in a style called Publix 1. Nicknamed Big Bertha, when installed it had four manuals (keyboards), twenty ranks (sets of pipes), eight sets of tuned percussion units, and all the sound effects needed to accompany the silent movies the theater originally screened. Twelve additional ranks of pipes, for a total of thirty-two, have been added, significantly expanding the tonal capabilities of the organ.

When the theater faced dwindling audiences because of suburban competition, it was the organ that saved it. The building owner, who planned to demolish it for surface parking, refused to sell the organ separately, so members of the Alabama Chapter of the American Theatre Organ Society raised funds to purchase the building that housed it. In 1987, the group formed the nonprofit Birmingham Landmarks for that purpose. Its operation of the venue, which hosted movies, concerts, and events, went toward paying off the $680,000 mortgage and enabled complete restoration, staged to minimize closure, in 1998–1999 (the theater was entirely closed for only about six months). In 2009, the group opened the space adjacent to the theater for a ballroom and reception area in order to accommodate expanded event offerings.

Today, the Alabama is one of only three historic theaters remaining in a multiblock district once full of theaters offering vaudeville, nickelodeons, silent and talking motion pictures, and live performances. The 1913 Lyric Theatre, built originally for vaudeville, stands across the street in the same block, and was fully restored in 2016. The circa 1941 Carver Cinema stands two-and-a-half blocks away in what was historically the African American business district. Both the Alabama and the Lyric had commercial office space associated with their buildings. Though no longer a center of shopping, and offering only little entertainment, the architecture of the remaining department store and theater buildings nevertheless establish a distinctive identity that has been instrumental in revitalizing what is now known as downtown Birmingham’s “entertainment district.”

References

Donaldson, Larry W. (long-time Alabama Theatre volunteer and Wurlitzer crew chief). Email communication with author, April 2015.

Lavoie, Catherine C., and Frederick J. Lindstrom, “Alabama Theatre,” Jefferson County, Alabama. Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS No. AL-982), 1996. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.