Among the oldest astronomical observatories in the United States, the Lowell Observatory was the site of the discovery of the dwarf planet Pluto in 1930, along with other scientific breakthroughs. It is the creation of Percival Lawrence Lowell (1855–1916), a brilliant mathematician and Boston Brahmin from a family that included noted American poets and academicians.

Lowell was already directing his family’s financial trusts, electric companies, and cotton mills (in Lowell, Massachusetts) when he became intrigued with the study of planets, particularly Mars. Believing the “red planet” exhibited signs of intelligent life, Lowell resolved to build his own observatory to investigate this hypothesis. After examining potential sites in Algeria, the Swiss Alps, Mexico, and California, he settled on a 7,000-foot-high mesa in Flagstaff, where the air was clear and calm.

The Town of Flagstaff, eager for the prestige, donated five acres and built a wagon road up the hill to ease the delivery of materials to the site. Construction began on what became Mars Hill in 1894 and lasted until the onset of the Great Depression. Most of the original structures were built of indigenous materials, including rough chunks of volcanic Malpaís rock and timber from the surrounding forest.

The Clark Dome, permanently sited in 1896, is the oldest existing structure in the observatory complex and still contains the original 24-inch, Alvan Clark and Sons refracting telescope. Godfrey Sykes, an Englishman who settled in Flagstaff in 1886 and operated a machine shop with his brother Stanley (who would work for the observatory for 46 years), designed the Clark Dome under the direction of astronomers A.E. Douglas and William Pickering. The building was designed with an upper portion that can be rotated with steel rollers to point the telescope toward different sections of the sky. When the dome proved too difficult to roll, an elevated trough filled with water was substituted for the rollers, on the theory that the dome would move by flotation. High winds at the site tended to rock the dome, causing brine to slosh down the dome’s interior, creating stains still visible today. In 1900, the dome was mounted on steel wheels with moderate success. In 1959, the lower ring of the dome was mounted on car tires in a track, the effective solution used today.

Percival Lowell’s third cousin, Guy Lowell (1870–1927), who studied architecture at MIT and the Ecole des Beaux Arts, designed the Slipher (Administration) Building to commemorate the work of brothers Vesto Melvin and Earl Slipher (in 1912, Vesto discovered the “red shift,” thought to indicate a continually expanding universe). The one-story structure was constructed of local materials in 1915–1916 under the direction of Stanley Sykes and Edward C. Mills to provide much needed office and darkroom space. Centrally located in the observatory complex, the fieldstone building features a Saturn-shaped rotunda in the center of the facade, a hemispherical, masonry dome supported by eight engaged Doric columns. Originally defined by a flat roof and a castellated parapet, a second floor with an attic and a hipped roof was added in 1923, partly to eliminate roof leaks but also to add office space. The rotunda served as a library and now functions as a visitor center. The Slipher Building was the last structure erected before Lowell’s death in 1916. In 1923, a granite mausoleum resembling an observatory was built in his honor.

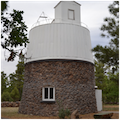

The dome from which the ninth planet in our solar system was discovered was not completed until 1929, due to funding shortages resulting from disputes over Lowell’s will. The building, now known as the Pluto Telescope Dome, was designed and constructed by Stanley Sykes and Edward C. Mills and has a concrete foundation, an exterior composed of volcanic rock, and a rotating metal roof. Inside, it houses the 13-inch-wide field search telescope that Clyde Tombaugh (1906–1997) used to identify Pluto. Tombaugh was a 23-year-old Kansan and amateur astronomer when was invited to the Lowell Observatory in December 1928 to help search for “Planet X.” Though he received room and board, Tombaugh was not paid for his work, which included manipulating the heavy dome, directing the cumbersome 13-inch telescope, and exposing, developing, and comparing 14- by 17-inch glass photographic plates—all in Flagstaff’s oft-freezing cold night air. His target was a tiny, moving object among millions of stars in the Milky Way galaxy. On February 18, 1930, Tombaugh saw a dot of light change positions: he had discovered Pluto almost exactly where Lowell had predicted it would be located.

Additional buildings were added to the campus as needed in the second half of the twentieth century, including the 1965 Planetary Research Center and the 1994 stone-and-concrete Steele Visitors Center. Today, the campus features housing for researchers, community water towers, telescope domes, and an instrument shop.

References

Durham, Michael S. Smithsonian Guide to Historic America: The Desert States.New York: Stewart, Tabori and Chang, 1990.

“History.” Lowell Observatory. Accessed August 6, 2014. http://www.lowell.edu/.

Jacobsen, Rebecca, “Lowell Observatory, Slipher Building,” Coconino County, Arizona. Historic American Building Survey, 1994. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS ARIZ,3-FLAG,1A-).

Patterson, Ann, and Mark Vinson. Landmark Buildings: Arizona’s Architectural Heritage.Phoenix: Arizona Highways, 2004.