You are here

Newark Earthworks

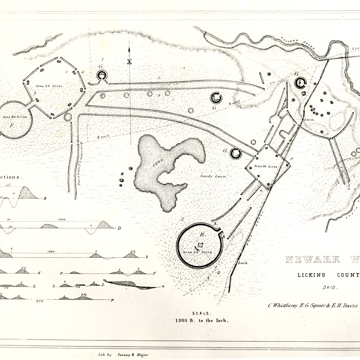

These earthworks are located on the western side of Newark near the Licking River and Raccoon Creek. Originally the earthworks complex of circles, squares, octagons, parallel embankments, and circular and elliptical mounds encompassed more than four square miles. As the City of Newark (founded in 1802) grew during the nineteenth century, large portions of the walls and many of the mounds were destroyed. Today, the Newark Earthworks includes the Great Circle Earthworks, Octagon Earthworks, and Wright Earthworks and is considered the largest grouping of geometric earthen enclosures in the world.

Likely used as a ceremonial center, the Great Circle Earthworks includes a circular structure surrounding an area of about 26 acres. Roughly 1,200 feet in diameter, the earthwork has 8-foot-high walls. Centered in the circle is the Eagle Mound. The Octagon Earthworks is 120 acres and features a large octagon and a circular embankment joined by parallel walls about 300 feet in length and 60 feet apart. Enclosing 50 acres, the octagon has openings at each of its 8 corners; within the octagon opposite these openings are small mounds. The circle encloses 20 acres. Opposite its entrance, in direct alignment with the parallel walls, Observatory Mound appears to be built across a former gateway; straddling the gateway, the mound is 12 feet tall—8 feet higher than the enclosure walls at that point. At present, the Octagon Earthworks is also the site of the golf course of the Mound Builders Country Club, founded in 1910.

The Wright Earthworks includes a small portion of one side of the square enclosure and a fragment of a parallel wall that connected a large oval enclosure to a square enclosure of near perfect geometry, of which only a portion remains. Originally, the sides of the Newark square ranged from about 940 to 950 feet in length, and enclosed about 20 acres.

Echoing the hills, valleys, and waterways that characterize the central Ohio River Valley, the Ohio Hopewell monumental mounds and earthworks are distinctive in their scale and complexity. They are unequalled by other ancient architectural monuments—the Great Pyramid at Giza, for example, would easily fit inside either the Wright Square at Newark Earthworks or the square earthwork at Seip (Hopewell Culture National Historical Park) in nearby Bainbridge. In fact, the main enclosure at Hopewell Mound Group (Hopewell Culture National Historical Park) is large enough to accommodate almost ten Egyptian pyramids.

This monumental earthen architecture demonstrates the creative genius of the peoples of the Hopewell Culture. Used for mortuary rituals and religious and social ceremonies, the earthworks were constructed to exacting geometric and astronomical specifications. The perfect circles, squares, and other geometric forms exhibit precise dimensions, many of which are repeated at sites located great distances from each other, and these forms are accurately aligned to movements of the sun and moon. In 1982, physicist Ray Hively and philosopher Robert Horn demonstrated that the Octagon Earthworks encoded alignments to the rising and setting of the moon over an 18.6-year-long cycle. Some consider this to be evidence for a lunar calendar, but it is more likely the alignments were intended to sacralize the architecture by linking it to the rhythms of the cosmos.

The earthworks also demonstrate that the Hopewell Culture was part of a larger network of more permanent communities based upon agricultural productivity and connected by the apparent exchange of materials between regions. Objects for ceremonial use that were discovered here are not merely exceptionally crafted, they are fashioned from exotic raw materials obtained from far-distant lands: copper from the Great Lakes, mica from the Appalachians, marine shell from the Gulf Coast, even obsidian from the Rocky Mountains.

In the 1840s, Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis conducted survey work that resulted in the first archaeological investigations to draw attention to the importance of the Hopewell Culture, in Ohio and elsewhere. Their surveys are documented in Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley of 1848, the Smithsonian Institution’s first publication. During the 1920s, the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society (now the Ohio History Connection) conducted further archaeological investigations and in the 1930s the sites were designated as state memorials. Newark Earthworks is recognized as a National Historic Landmark and is under consideration as a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks nomination. Today, Ohio History Connection continues to oversee the site’s preservation.

References

Hively, R., and R. Horn. “Geometry and astronomy in prehistoric Ohio.” Archaeoastronomy4 (1982): S1-S20.

Lepper, Bradley T. Ohio Archaeology: an illustrated chronicle of Ohio's ancient American Indian cultures. Wilmington, OH: Orange Frazer Press, 2005.

Lepper, Bradley T. “The Newark Earthworks, Monumental Geometry and Astronomy at a Hopewellian Pilgrimage Center.” In Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand: American Indian Art of the Ancient Midwest and South, edited by Richard F. Townsend and Robert V. Sharp. New Haven: Yale University Press and The Art Institute of Chicago, 2014.

Lynott, Mark J. Hopewell Ceremonial Landscapes of Ohio, More than Mounds and Geometric Earthworks. American Landscapes Series. Havertown, PA: Oxbow Books, 2015.

Squier, Ephraim G., and Davis, Edwin H. Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley.1848. Reprint, Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Weiss, Francine, “Newark Earthworks (Mound Builders State Memorial, Octagon State Memorial, Wright Earthworks),” Licking County, Ohio. National Historic Landmark Nomination, 1975. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.