This Masonic temple stands on the cliff of a prominent ridge facing Main Street (U.S. 6) just south of Woodbury. The building displays Greek Revival influence and deep Masonic themes in its design.

In eighteenth-century Connecticut, the values of liberty, equality, and fraternity aligned the Masons with the aims of Revolutionary Americans. Fraternity was a popular virtue for colonists because their social connections and positions in the New World were severed from the strict order of the Old World. It was within this setting, and its implicit desire for stability, community, and social rank, that the brothers of Woodbury formed their Lodge on the Rock, now considered the oldest Masonic temple in continuous use in Connecticut.

In the early period of Masonry, dating back to the middle ages in Europe, the guild was a trade organization established to regulate stoneworking. The Masons, dedicated to craft traditions, charity, and building fraternal ties, claim descent from Hiram Abiff, the master workman for the building of Solomon’s Temple, and are linked to the ancient Greek geometer Euclid. The group’s secret practices, dating from its inception, included codified handshakes and passwords, which helped identify the level of skill in mobile building trades. Confidentiality also gave the group a shadowy mystique that fueled anti-Masonic sentiment and conspiratorial rumors throughout its history. In 1717, four London lodges appointed a layperson—instead of a craftsperson—as the Grand Lodge Master. This marked a shift toward speculative Masonry, wherein members were unconnected to the building trades. Ceremony and ritual activity took on a heightened importance at this time, and solemn respect for order was appealing to speculative Masons in colonial America.

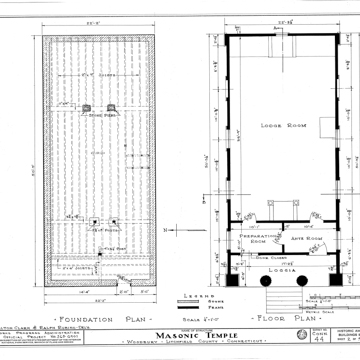

The charter that formed King Solomon’s Lodge No. 7 was issued by the Provincial Grand Lodge of Boston on July 17, 1765. The guild was slow to start; its first meeting did not take place until December 1775. The economic downturn caused by the War of 1812 further delayed the building of a lodge. In 1838, land was purchased from Ashbel Moody for the sum of $15, but Moody’s son-in-law, Levi Douglas, passionately disliked Masons and refused their request to transport materials to build the lodge across the family’s land. Thus, the Masons had to transport building materials up the steep cliff, resulting in the cliffside stairs, now an iconic marker of the lodge’s architecture. Douglas’s anti-Masonic sentiment was not unusual in this period—a reaction to its presumed power to undermine religious and republican values. Despite this, the group in Woodbury continued to raise funds, and in 1839 they completed construction of their lodge.

The building was designed by Horace Oatman, who was neither a Mason nor a professional architect. (At the time, builders with flair for design were designated as architect-builders.) By 1866, due to the success of his work, Oatman had become a Mason. The pair of sturdy Doric columns flanking the doorway recall historic images of King Solomon’s Temple, albeit in a Greek Revival style. The columns and pilasters and the simple entablature and pediment are robust, projecting solidity and asserting the Masons’ dominance on the hill.

The first bay previously opened to the entrance hall. In the late 1800s, its windows were boarded over to reduce the illumination in the space. The central two bays remain as originally built. In the 1890s, when the lodge was expanded to the east, another bay was added. This fourth bay contains a false window—one of a number of architectural subterfuges the lodge contains. The interior has always been markedly more ornate than the simple exterior. The lodge room at the center of the building was originally dark and mysterious; intricate carpets emblazoned with Masonic symbols covered the floor and ornate wallpaper displayed trompe l'oeil architectural details, a favored design element here throughout much of its history. The effect of this highly patterned room would have been dazzling, befitting the mysterious pageantry of the guild. By 1937 the walls were adorned with applied Corinthian columns. The use of illusion to represent architectural detail shows the Masons’ commitment to devotion to building craft, even when budget precluded the purchase of such structural elements.

In 2014, the Woodbury Masons began a renovation of the lodge. Much of the work was done by the Masons themselves, following in the tradition of their precursors, and the Lodge on the Rock retains its status as a landmark of historic architecture and Freemasonry in Connecticut.

References

Bullock, Steven C. Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730–1840. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996

Gaudioso, Lorenzo , Fred Holzbaur, John Novak, John Monteleone, John Stack, and Albin Weber (members of the lodge’s historical society), interview by author, Woodbury, CT, 31 July 2019.

Hamlin, Talbot. Greek Revival Architecture in America: Being an Account of Important Trends in American Architecture and American Life Prior to the War between the States. New York: Dover Publications, 1944.

Sakavich, Al. “Our Lodge History.” King Solomon’s Lodge No. 7. https://lodge007.ctfreemasons.net/our-lodge-history/ (retrieved August 25, 2019).