You are here

Scroll and Key Society Building

The Scroll and Key Society Building, often inaccurately referred to as a tomb, is the home of Yale University’s second oldest secret society. It is the only remaining building by Richard Morris Hunt on Yale’s campus; his Gothic Revival East Divinity Hall and the adjacent Marquand Chapel were torn down in the 1930s. The Moorish Revival style applied here, widely admired at the time, is also unusual for Hunt’s architecture.

Scroll and Key, legally known as the Kingsley Trust Association, was founded in 1842 after disputes arose among members of Yale’s first fraternity, Skull and Bones. Initially, the society’s meetings took place in rented facilities in downtown New Haven. In 1856, Skull and Bones built a permanent home designed by Alexander Jackson Davis in the heart of Yale’s campus. Scroll and Key society members felt the need to do the same, and engaged Hunt for the project.

The dedication to “the study of literature and taste” lies at the heart of Scroll and Key’s philosophy, and the society’s new home had to reflect this ideal. This philosophy might have been the impetus for the building’s Moorish Revival design. From the early nineteenth century on, artists such as Delacroix, Ingres, and Gérôme became fascinated by exotic subjects, which were often labeled “oriental” at the time. The Moorish facade not only added to the mystery of what was taking place inside this “tomb,” but also indicated that Scroll and Key members were in tune with the broader artistic culture of the time.

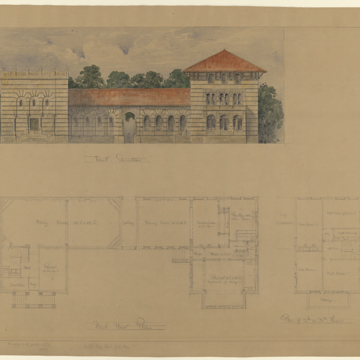

A surviving drawing from circa 1869 indicates that Hunt originally planned a much larger building with a flat-roofed two-story wing, a pitched-roofed passageway, and a second wing with three stories, eight bedrooms, and a pitched roof. Only the two-story Moorish wing was built. It is possible that this compromise was due not only to financial constraints, but political and logistical ones as well. It took quite some time and effort before Scroll and Key was able to purchase land on Yale’s campus (perhaps because of the machinations of Skull and Bones), and the lot they acquired presented further limitations.

As it stands today, the Scroll and Key Society Building is compact and symmetrical in its design. The exterior masonry features thin dark-striped bands against light-colored stone. Four narrow granite columns—two thinner red ones and two slightly larger grey ones—are topped with bright white capitals, reminiscent of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. The columns elevate the three blind arches, which mark the front entrance of the building. An elaborately carved impost band with arabesque motifs rests above the heavy black door. The parapet features six octagonal stars and four octagonal posts topped with pointed domes. These stars and imposts reoccur on the cornice design. The deep-set windows on the front, sides, and the back of the building are long narrow arches and consist of stone window screens with three small carved openings. The cast-iron fence surrounding the building features Moorish-inspired horseshoe arches and was added a few years later due to budget constraints. In 1901, the building was seamlessly extended to its northwestern end.

The building is still used by the Scroll and Key Society and was extensively renovated in 2010.

References

Baker, Paul R. Richard Morris Hunt. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1980.

Brown, Elizabeth Mills. New Haven: A Guide to Architecture and Urban Design. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

Danby, Miles. Moorish Style. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1995.

Pinnell, Patrick L. The Campus Guide: Yale University. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999.

Richards, David A. “The Origins of the Tomb: How Skull and Bones Found a Home.” Yale Alumni Magazine 78, no. 5 (May/June 2015): 36-41.

Scully, Vincent, Catherine Lynn, Erik Vogt, and Paul Goldberger. Yale in New Haven: Architecture & Urbanism. New Haven: Yale University, 2004.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.