This Italianate villa was built for Sally Dorsey of the prominent Dorsey family of Howard County as part of a gentlewoman’s farm. The Dorseys were descendants of Colonel Edward Dorsey, who received an early Maryland land grant around 1690. They owned many of the finest farms and plantations in Howard County and distinguished themselves in politics, law, military service, agriculture, and business. Sally Dorsey's land formed a portion of the 900-acre Mount Hebron estate of her father, Judge Thomas Beale Dorsey Jr., divided among his three children after his death in 1852. Her brother William also hired architect Norris Garshom Starkweather to build an Italianate villa, known as “Wilton,” across the road.

The villa became a sought-after form for genteel farmers such as the Dorseys anxious to showcase their refined taste. By embracing the form, Dorsey acknowledged her awareness of the latest trends in both picturesque architectural and landscape design. The development of Italianate and Gothic Revival villas and cottages during the mid-nineteenth century was part of a larger picturesque aesthetic that began in England. The movement was made popular in the United States by individuals such as Andrew Jackson Downing, whose path-breaking The Architecture of Country Houses (1850) dominated the pattern book market while setting standards for good taste and livability in the housing design of the era. Downing’s book was the first to target the potential homeowner rather than the house carpenter, and it appealed to a broad consumer market that reflected the rise of the middle class. Through such publications, Downing and others elevated the humble cottage—which in England had been synonymous with poverty—to a housing form suitable across social spectrums. This was accomplished in part by linking cottage architecture to its bucolic landscape settings.

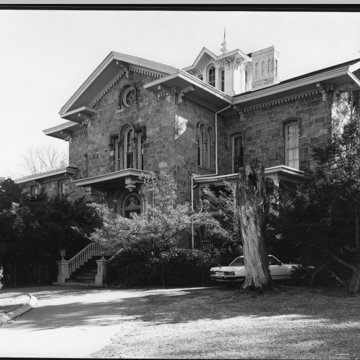

Elmonte is constructed of indigenous, random-laid ashlar granite. The central three-bay-wide main block appears symmetrically balanced from the front elevation but this symmetry falls apart when viewed from other perspectives. The parlor extends from the west facade, the center hall extends to the rear, and there is a service wing set back to the east side. The drive was laid out so that upon approach the service wing is not immediately visible, which is also in keeping with Downing’s philosophy. Likewise, the veranda extends the length of the front facade and returns to either side to further obscure the side projections. Elmonte’s character-defining exterior details include segmentally arched drip-mold window hoods, paired and tripartite window arrangements, an overhanging hipped roof supported by large brackets, a center gable peak, a cupola pierced by round-arched windows, and ornamental brick chimneys.

The asymmetrical interior plan includes a center hall that runs the depth of the house, widening to the rear to accommodate a stairway. To the west side of the center hall are adjoining library and parlor rooms separated by pocket doors. To the east is the dining room with a perpendicular hall running between it and the service area. The open-well, open-string stairway cantilevers along the east wall with a quarter turn at the base and winds its way to the third floor. Designed to accommodate servant labor, the extensive service area includes a secondary stairway, laundry (now bath and closet), pantry, and kitchen with fireplace. The second floor follows the same plan as the first, with the exception of the area over the service wing, which is divided into smaller bedchambers, likely for servant use. More bedchambers are found in the finished third floor. Elmonte retains its original interior details including complex plaster cornices, wide architraves and baseboards, marble mantels, and gas-lit chandeliers.

Starkweather was a prominent Baltimore architect best known for his ecclesiastic structures and villa-style residences. He began his career in Philadelphia, where he worked briefly with Joseph C. Hoxie before moving to Baltimore in 1856, where the First Presbyterian Church became one of his most enduring designs. Starkweather undertook numerous villa designs in Baltimore and Howard counties, including one noted example for the church’s minister, John Backus. Starkweather continued his ecclesiastic work in Howard County, including St. John’s Church (paid for by the Dorsey family) and the chapel at the Patapsco Female Institute, both in Ellicott City, the county seat. He later worked in Washington, D.C. and New York City.

The Elmonte house now sits on 3.11 acres surrounded by a subdivision.

References

Andreve, George J. “Elmonte” (Twiford), Howard County, Maryland. National Register Nomination Form, 1976. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Downing, A.J. The Architecture of Country Houses. 1850. Reprint, with an introduction by J. Stewart Johnson, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1969.

Moss, Roger, and Sandra Tatman. “Starkweather, Norris Garshom (1818-1885).” In Biography from the American Architects and Buildingsdatabase. Accessed May 10, 2016. http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/25631.