Fort Morgan and its counterpart, Fort Gaines, face each other across a three-mile expanse of open water, guarding the mouth of Mobile Bay where it empties into the Gulf of Mexico. The older and larger of the two defenses, Fort Morgan, stands on Mobile Point at the westernmost tip of a thin, 18-mile long peninsula separating the Bay from the Gulf. Fort Gaines perches at the easternmost point of Dauphin Island, one of the sandy, low-lying barrier islands that stretch along the semitropical Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas.

Both installations were ambitiously conceived by the federal government following the War of 1812 as part of a string of defensive installations guarding the east coast of the United States against maritime invasion. Extending as far north as Maine, these were collectively designated a “Third System” of American coastal fortifications (distinguishing it from two earlier initiatives launched in 1794 and 1802). Forts Morgan and Gaines were envisioned to defend the mouth of Mobile Bay, replacing the dilapidated Fort Conde built by the French in the mid-1700s on the Mobile River, at the head of the bay some thirty miles north.

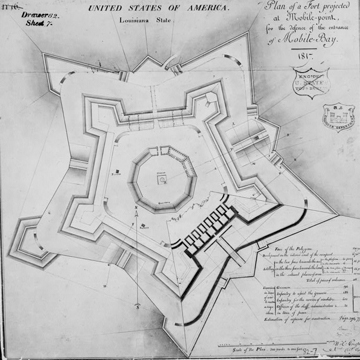

In 1817 Captain William Tell Paupin used a design by French-born military engineer Bernard Simon for a massive brick structure later named in honor of Revolutionary War hero General Daniel Morgan. Simon, a graduate of the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, a veteran of Waterloo, and a Napoleonic exile, held the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. Army. Besides Fort Morgan, he would also prepare designs for similar installations at Fort Monroe, near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia, and Fort Adams on Narragansett Bay at Newport, Rhode Island.

The Alabama fortification was built on the site of Fort Bowyer, a hastily built stockade and earthwork that had seen action between British forces and those of General Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812. Simon’s plan called for a traditional, five-sided, star-shaped structure after the manner popularized in the seventeenth century by an earlier French military engineer, the famed Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban. With a total circumference of more than a quarter of a mile, Fort Morgan’s 24-foot-high curtain walls stretch 264 feet between each of five jutting, angular bastions. Beneath a terraplain reached by steep flights of granite steps, a series of vaulted casements encircle the parade ground. Piercing the sloping outer walls of the fort, 54 gun embrasures command a field of fire across a wide, dry moat and the earth-topped outer defense works beyond.

Entry is on the landward side through a handsome portal surrounded by bold granite rustication and framed by Tuscan pilasters that carry a full neoclassical entablature. Carved in a plaque immediately above the gate is the word “Morgan” and the date “1833”—the year the fort received its official name. The parade ground originally centered on a 10-sided brick “citadel” studded with a triple row of gun ports. Like the keep of a medieval castle, the citadel offered a last-ditch defense should an attack force breach the outer walls.

After a fitful start in 1819, marred by the death of the original contractor among other difficulties, construction on Fort Morgan finally commenced in earnest in 1821. It is estimated that nearly 47 million cubic feet of masonry went into the project, including a jetty extending into Mobile Sound, as well as enlisted men’s barracks and officers’ quarters constructed outside the fort facing the Gulf of Mexico. Brick was burned at kilns on Fish River, which flows into the eastern side of Mobile Bay. Labor was furnished by a combination of free white and enslaved African American workmen; the Army contracted with area enslavers for the latter. Intermittently manned as a military post during the 1840s and 1850s, Fort Morgan was also used as an assembly point in the late 1830s for the removal of Native Americans (local Creeks and Choctaws) to what is now Oklahoma.

Anticipating Alabama’s imminent secession from the Union, state militia seized Fort Morgan in a surprise pre-dawn action on January 4, 1861. Over the next three years, the fort’s guns provided cover for Confederate blockade runners outbound from the city of Mobile and inbound from Havana and Nassau. But on August 5, 1864, following a fierce engagement with Confederate ironclads, federal naval forces under Admiral David Farragut regained control of Mobile Bay. (The battle is remembered in popular American lore for Farragut’s famous, if apocryphal, order to “Damn the torpedoes and full speed ahead!”) On August 8, Fort Morgan’s companion defense work, Fort Gaines, fell, and two weeks later the beleaguered garrison of Morgan surrendered following heavy Union bombardment. The end of the Civil War found the fort heavily damaged, its citadel gutted and the outlying barracks destroyed.

Although repaired in the late 1860s, Fort Morgan languished for the next three decades even as advances in armaments and naval artillery posed the need (so argued proponents) for a new generation of more powerful American coastal defenses. Congress responded in 1885 with the establishment of a Board on Fortifications and Other Defenses (popularly called the “Endicott Board” for its chairman, Senator William Crowninshield Endicott), under which Fort Morgan would be expanded and upgraded. Beginning in 1895 and into the early 1900s, five large, reinforced concrete gun batteries were constructed. These included the mammoth Battery Duportail (1898–1900), built inside the fort partly on the footprint of the destroyed citadel, and Battery Dearborn, located well away from the main fort to the east. Frame barracks and officers’ quarters, extensively galleried against long hot summers, were also erected to the east of the fort overlooking Mobile Bay. (Most of these structures were lost to storm and hurricanes during the late twentieth century.)

Fort Morgan remained continuously garrisoned from 1898 until 1924, with as many as 2,000 troops stationed there during World War I. A so-called “Test Battery,” the only one of its kind in the United States, was built in 1915 and subjected to a three-day naval bombardment in order to test its durability. The battery survived, although it is now partially buried in sand near the fort. But the steady advance of modern armaments would render such coastal defense works as Fort Morgan increasingly archaic. In 1923 it was declared obsolete and in 1927 the property was sold to the State of Alabama. Activated briefly during World War II to counter the German submarine threat in Gulf of Mexico, it was then returned to the State. In 1960, the Secretary of the Interior designated Fort Morgan a National Historical Landmark. Now a state historic site administered by the Alabama Historical Commission, the fort is open to the public and illustrates 200 years of evolving American military architecture.

References

Davis, Virgil S. A History of the Mobile District: 1815-1971. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, n.d.

Lewis, Emanuel Raymond. Seacoast Fortifications of the United States: An Introductory History. Annapolis, MD: Leeward Publications, 1970.

Robinson, Willard B. “Military Architecture at Mobile Bay.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 30 (May 1970): 119-139.

Weaver, John R. A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press, 2001.