You are here

Moundville Archaeological Site

To early-nineteenth-century Anglo-American settlers, the earthen mounds they encountered along the Black Warrior River and other Alabama waterways presented a tantalizing mystery. Some speculated about a vanished race of “Mound Builders;” others, more biblically grounded, wondered if they were a testament to the “Lost Tribes of Israel.” Most found it hard to associate them in any way with the dispirited native tribesmen around them, glumly awaiting their forced exile to the West.

If anthropological and archaeological research has long dispelled the theories about the mounds’ origin, the Mississippian Culture that produced them still remains but vaguely understood. Broadly speaking, its communities waxed and waned for some eight hundred years, from around 800 CE to 1600 CE, at different times and in different places across a broad swath of eastern North America. Nearly a hundred Mississippian sites have been identified from the upper Great Lakes and the vast Mississippi-Ohio River drainage area, south to the Gulf of Mexico, and east across Alabama and Georgia into the Carolinas. Bound together in an extensive if loose trading network covering thousands of square miles, Mississippian communities shared similar cultural traits and belief systems. In the eleventh century, Cahokia, located in present-day Illinois across the Mississippi River from Saint Louis, Missouri, emerged as the preeminent Mississippian center population-wise and economically as well as, so archaeologists believe, religiously. Not long thereafter Moundville, five hundred miles to the southeast in Alabama, also began to rise to prominence as a regional center of the culture. Though hardly comparing in sheer scale to its Illinois counterpart, Moundville ranks as one of the most important sites of Mississippian culture. Its mound complex, together with a scattering of other Pre-Columbian mounds around the state, are man’s oldest surviving architectural imprint on the Alabama landscape.

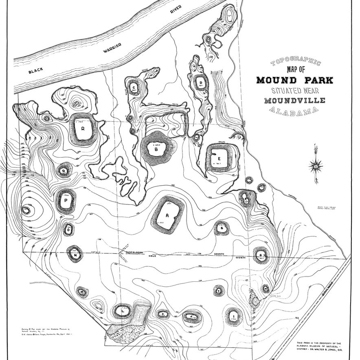

Altogether the complex encompasses some 320 acres, 185 of which are preserved and administered by the University of Alabama as the Moundville Archaeological Site. South of a fringe of woodland along the low-lying bluffs of the Black Warrior River, twenty-nine mounds are positioned irregularly around a vast central plaza—a conceptual form repeatedly seen at Mississippian sites. While the surrounding countryside may already have been heavily populated, artifacts discovered on site suggest that leveling and filling for the plaza area itself probably began around 1200. Most of the encircling mounds, ranging from three to fifty-seven feet in height, are built as steep-sided platforms, square or rectangular at the base, with one or more earthen access ramps. Consensus among archaeologists is that the impermanent wooden structures atop the larger mounds may have served as dwellings for the community elite—an architectural expression of the Mississippian Culture’s innately hierarchical society. The tallest mound, flanked by two slightly smaller mounds, lies at the northern end of the plaza, with other mounds to either side of the plaza decreasing in size from north to south. Thus archaeologists have concluded that Moundville’s layout, too, expresses a strict social hierarchy.

At the Moundville site’s zenith, more than a thousand people are believed to have lived within the wooden palisade that, running south from the river, encircled the great plaza and its contiguous mound dwellings and ceremonial structures. Beyond, in the area surrounding the nuclear community may have lived as many as ten thousand more people constituting, perhaps, a sort of native peasantry.

Sustained by maize and other cultivated crops, together with fish and wildlife from the river and surrounding forests, Moundville flourished between roughly 1250 and sometime after 1350, and then declined for reasons that still remain unclear. Though perhaps occupied, at least in part, as late as the 1500s, the site seems to have been used increasingly as a necropolis.

While early Alabama antiquarians occasionally took note of the mounds along the Black Warrior, the first serious scholarly consideration of the Moundville site occurred when pioneering archaeologists Edwin Hamilton Davis and Ephraim G. Squier pronounced it one of the North America’s largest mound complexes in their Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1848. But sustained archaeological investigation would have to wait more than half a century, until the early 1900s, when Philadelphia antiquarian Clarence Bloomfield Moore of Philadelphia spent two wintry months in 1905–1906 excavating at the site. Moore’s detailed reports and artifact discoveries underscored Moundville’s importance. Unfortunately, they also brought unwanted public attention that, in turn, fostered looting. Finally, in 1929, concerned local citizens, aided by Dr. Walter B. Jones of the Alabama Museum of Natural History at the nearby University of Alabama, began piecemeal acquisition of the property from private landowners in order to place the Moundville site under state protection. Jones, meanwhile, spearheaded the first prolonged excavations there.

Encouraged by the federal cultural and natural conservation programs initiated under President Franklin Roosevelt, Alabama legislators created Mound State Park (renamed Mound State Monument five years later) in 1933. Subsequent development of the site in the late 1930s, using Civilian Conservation Corps labor, included construction of the present Walter B. Jones Museum building as well as cottages for the park superintendent and staff. The stark yet pleasing horizontal linearity of the museum building itself, constructed of poured concrete, references the swelling tide of 1930s modernism. Frieze panels running along the exterior incorporated motifs derived from artifacts excavated at Moundville. While the building’s architect is not identified, some have suggested early Tuscaloosa modernist Don Buel Schuyler.

In a move that would have startled a later generation more attuned to cultural appropriateness, the museum was placed over a large indigenous burial site that had been excavated. From a mezzanine viewing area, visitors could thus peer down at the skeletal remains of Moundville’s prehistoric inhabitants. In the 1990s, however, the remains were removed from view, relocated for safekeeping to the University of Alabama, and the burial site sealed. A multimillion dollar renovation of the museum building, completed in 2010, expanded the structure to the rear while introducing state-of-the-art display and curatorial space.

Now known as Moundville Archaeological Park, other development has included selective reconstruction of typical aboriginal dwelling types in the park area and atop the largest of the mounds comprising the complex.

References

Blitz, John H. Moundville.Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

Hamilton, Edward Davis, and Ephraim G. Squier. Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations. Edited by Joseph Henry, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution. New York: Bartlett and Welford, 1848.

Knight, James Vernon James Jr., with contributions by H. Edwin Jackson and Susan L. Scott. Mound Excavations at Moundville: Architecture, Elites and Social Order. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010.

Knight, Vernon James Jr., and Vincas P. Steponaitis. Archaeology of the Moundville Chiefdom.Washington: Smithsonian Press, 1998.

Walthall, John A. Moundville: An Introduction to the Archaeology of a Mississippian Chiefdom.Special Publication No. 1, Alabama Museum of Natural History. 2nd edition. Tuscaloosa: Alabama Museum of Natural History, 1994.

Wilson, Gregory D. The Archaeology of Everyday Life at Moundville.Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.