You are here

Sloss Furnaces

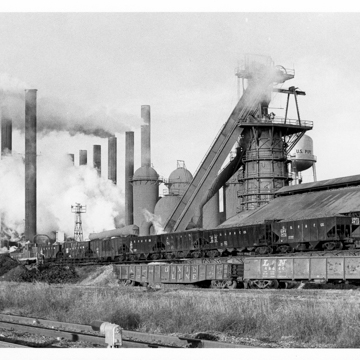

The striking silhouette of Sloss Furnaces and the still-busy railroad tracks around them in downtown Birmingham tell the story of why the city came into being shortly after the Civil War. Due to its large deposits of iron ore, coal, and limestone, within a decade and a half of Birmingham’s founding, six blast furnaces lined the railroad tracks. The gargantuan scale of the furnaces, stoves, and stacks dominated the skyline, and stood as a testament to an industrial process that drove the country’s economy and dwarfed the human figures working it. Birmingham became the nation’s leading foundry iron producer from the late nineteenth century until the 1960s. Today, only the long-dormant Sloss complex remains.

Originally blown in 1882 and 1883, the two blast furnaces were extensively rebuilt and modernized during the 1920s, resulting in a daily capacity of 400 to 450 tons. They continue to anchor a group of some forty iron-making structures, including steam boilers, a powerhouse, blowing engine room, hot blast stoves, expanded slag machine, slag pits, cast houses, office, cooling towers, spray pond, gas washing equipment, storage bins, bathhouse, and railroad tracks. Now a National Historic Landmark, the complex is a monument to Birmingham’s origins and a pioneering model for preserving and interpreting a historic twentieth-century industrial site.

The oldest extant building, dating from 1902, houses immense vertical steam-driven blowing engines used to provide air for combustion in the furnaces. Boilers installed in 1906 and 1914 produced steam for operations until production ceased in 1970. The causes of the shutdown were complex: a declining market for merchant pig iron, satisfying air pollution requirements, and the high cost of metallurgical coke. In 1977 Birmingham voters, faced with a proposal to demolish the city’s last remaining historic furnace complex, approved a $3 million bond issue to convert it into an industrial museum, which opened in 1983.

In addition to on-site interpretation that counts the structures among its primary exhibits, the city-owned museum conducts an innovative metal arts program and hosts exhibitions and workshops that include casting and blacksmithing artists working on site. Concerts, festivals, conferences, and social events also draw people from throughout the community, bringing new life and new attachments to the historic furnaces. The opening of a new visitor center in 2015 further expanded offerings for study, interpretation, and events.

References

“History.” Sloss Furnaces. Accessed April 10, 2017. www.slossfurnaces.com.

Kulik, Gary B., “Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron Company Furnaces,” Jefferson County, Alabama. Historic American Engineering Record (HAER AL-3). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Lewis, W. David. Sloss Furnaces and the Rise of the Birmingham District: An Industrial Epic. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.

Morris, Philip A. and Marjorie L. White. Birmingham Bound: An Atlas of the South’s Premier Industrial Region.Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Historical Society, 1997.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.