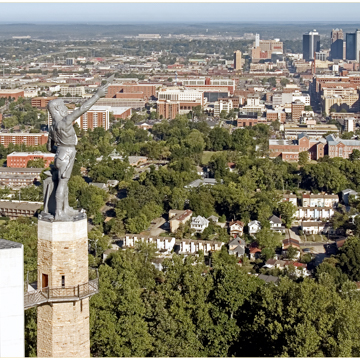

Conceived as a symbol of the city it now overlooks, the statue of Vulcan, Roman god of the forge, has represented Birmingham’s industrial roots for more than a century—first at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World’s Fair) in 1904 and, since 1937, standing atop the mountain of iron ore that once fed city furnaces. The gigantic statue is a testament to the fledgling city’s enterprise and natural resources; it is the largest iron figure ever cast, making it one of the most memorable works of civic art in the United States.

Italian-born sculptor Giuseppe Moretti created the 56-foot colossus on an exceedingly ambitious schedule. In his New York studio, he created the model from which full-size plaster molds were made and shipped in sections by train to Birmingham. There, with Moretti on hand, Birmingham Steel and Iron Company made the foundry molds, dug a large pit, and cast the statue in sections, using local pig iron made from locally mined minerals. Less than six months after Moretti was hired, Vulcan stood in the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy in St. Louis, towering over the other exhibits and promoting Alabama’s, and in particular Birmingham’s, industrial resources. San Francisco and St. Louis offered to buy the sculpture at the fair’s end, but Vulcan was shipped back to Birmingham. It lay in pieces beside the train tracks until it was finally erected at the Alabama State Fairgrounds.

Some 30 years later, in 1935, the Birmingham Kiwanis Club led an effort to restore the statue’s civic identity by moving it to a site atop Red Mountain (named for its iron ore) that was being transformed into a 4.45-acre park with funding from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Warren, Knight and Davis, a prominent Birmingham firm, designed a slender polygonal tower to make the statue more visible in the park and throughout the city. The architects selected a native split-faced sandstone from a nearby quarry to clad the Art Moderne tower and its octagonal base; the sandstone was also used for walls, walks, stairs, and benches. Three shallow pools joined by stone cascades defined a dramatic approach from a small parking area to the tower’s entrance on the south.

Three decades later, a modernization effort compromised the original scale, materials, and design when the tower was encased in white marble, an enclosed observation deck replaced the original open-air balcony, and other bulky elements, including an exterior elevator and a gift shop, were added. The site was regraded and the cascade destroyed. By the late 1990s, concrete used as ballast in the statue when it was placed on the tower was cracking the iron because of the materials’ varied rates of expansion, exacerbated by water penetration. The park was closed as a safety precaution.

The park’s closing triggered a groundswell of popular support for restoring the statue and its environs, in order to emphasize the icon’s visual and emotional impact. Specialty foundry Robinson Iron engineered the statue’s dismantling from the 123.5-foot-tall tower without further damage. Robinson Iron then undertook a painstaking restoration, including recreating a long lost spear point and second hammer. The statue was fitted with a complex stainless steel armature to provide support; the reinstallation required 11 crane lifts. The original base and open-air balcony were recreated, guided by the 1930s architectural drawings. A replacement elevator, required for accessibility, was designed as a slender, freestanding concrete structure placed on the south side of the tower, screened from the main city view. A new visitors’ center was designed to relate to the historic setting by its materials and low profile. The park was refurbished to convey its original character, including restoring remaining WPA stonework. Vulcan’s transformation from a colossal statue viewed at ground-level in a temporary indoor setting to an elevated outdoor monument has allowed it to remain an enduring symbol of Birmingham’s industrial history.

References

Birmingham’s Vulcan.1938. A facsimile of the original edition. Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Historical Society, 1999.

Kelley, Barbara T., editor. Birmingham Rocks: History and Use of Native Sandstone in Our Architecture and Landscape.Birmingham, AL: Vulcan Park Foundation, 2008.

Kierstead, Matthew. Historic American Engineering Record, Vulcan Statue and Park, haer no. al-29 , HAER ala 37-birm, 48 -

Morris, Philip A. Vulcan & His Times.Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Historical Society, 1995.