You are here

Manning Hall, Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind

This imposing building was erected to house the short-lived East Alabama Masonic Female Institute. In a state with little support for public schools, it usually fell to such private academies to educate the young beyond the bare rudiments of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Often the schools were affiliated with a particular religious denomination, and from time to time with the Masons, who viewed education as part of their philanthropic mission to society. On April 12, 1850, the Masons of Talladega ceremoniously laid the cornerstone for a school dedicated to the instruction of young women.

Chosen as designer for the building was brickmason-turned-architect Hiram Harrison Higgins (1802–1874) who, from the 1830s to the early 1870s, constructed residences, schools, and courthouses across a wide swath of Alabama and probably further afield. Born in Mount Sterling, Kentucky, Higgins had relocated to Athens in northern Alabama around 1835. His concept for the Talladega school, in fact, drew upon a similar design he had prepared six years earlier for the Methodist-affiliated Athens Female Institute. (Today known as Founders Hall on the Athens State University campus, the building now sports an incongruous mansard roofline.) Soon after construction started in Talladega, the cornerstone was laid for a third Higgins-designed girls’ school (long since destroyed) a hundred miles to the southwest, at Lowndesboro.

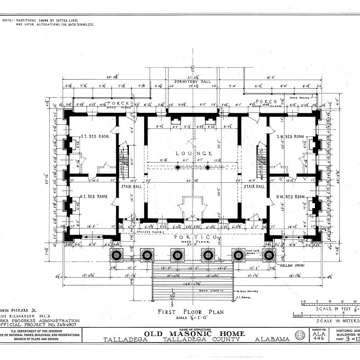

All three buildings were fronted by bold Ionic porticoes, and the Athens and Talladega schools were, as first built, nearly identical in appearance. But Higgins gave the Talladega building more visual presence and usable interior space by placing the two main floors above a raised basement. Partially recessed, pedimented colonnades front both buildings, though in Talladega Higgins turned the corner antae into an additional pair of voluptuous, full-blown Ionic pillars. Large three-part windows set into pilastered bays on either side—a feature often seen in central Kentucky as well—may suggest Higgins’ background. At Talladega, the crowning entablature is widened to accommodate a series of grilled frieze windows that light a third floor tucked beneath the slope of the broad gabled roof. Nearly identical in overall dimensions, both the Athens and Talladega schools followed a similar footprint: parallel through-corridors sandwich a large common area on both floors, with smaller, flanking rooms at each end of the building. The arrangement accommodated classrooms, assembly halls, dormitories, and dining, but precisely how each space initially served these functions is not altogether certain. Dining, however, was probably in the basement, with sleeping areas for boarding students relegated to the second floor and perhaps the third.

Despite a large public subscription and Talladega’s location in the center of a flourishing upland plantation district, the Masonic vision for female education soon proved an ambitious overreach. In 1855 the debt-burdened school was turned over to the Alabama Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, in hopes of perpetuating the ideal. But this, too, failed. Finally, in 1860, the State of Alabama acquired the building and its thirteen-acre campus to house the recently established Alabama School for the Deaf, later reincorporated in 1870 as the Alabama Institute for the Deaf, Dumb and Blind.

Named Manning Hall in 1929 to honor a former school director, the building remains the center of an evolving campus for what has today become the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind. Renovations in 1975 included replacement of a broad flight of late-nineteenth-century cast-iron steps leading up to the main portico with a set of twin curving stairs. From the standpoint of architectural history, Manning Hall suggests the unabashed manner in which successful institutional design—whether for schools, courthouses, or churches—was often copied from place to place. As a preeminent example in Alabama of institutional Greek Revival design, it also illustrates the creative way in which neoclassical forms could be manipulated for function and effect.

References

Couch, Robert Hill, and Jack Hawkins Jr. Out of Silence and Darkness: The History of the Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind, 1858-1983. Troy, AL: Troy State University Press, 1983.

Gamble, Robert. The Alabama Catalog - Historic American Building Survey: A Guide to the Early Architecture of the State.Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1986.

Jemison, E. Grace. Historic Tales of Talladega. Huntsville, AL: The Strode Publishers, Inc., 1959.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.