Mission Inn Hotel & Spa

The largest and best-known example of Mission Revival architecture in California is the Mission Inn, located in Riverside, approximately 55 miles east of Los Angeles. Developed over decades by owner Frank Augustus Miller (1858–1935), the luxury hotel was initially constructed in 1903. By 1932, the compound sprawled to encompass an entire city block (more than three acres) in downtown Riverside, at the heart of the commercial center. Today, the Mission Inn marks the start of a leafy, three-block-long pedestrian mall on Main Street that terminates in the Riverside City Hall, solidifying the hotel’s importance as both a local and tourist landmark.

Miller’s family first operated a modest boardinghouse, the Glenwood Cottage, out of a two-story, twelve-room, adobe and wood structure built on the site in 1876 and expanded in 1878. In 1880, Miller purchased the property from his father and continued to expand the hotel. By 1890, however, Riverside had become a wealthy city associated with the orange industry, and Miller devised an ambitious scheme to replace the sprawling inn with a grand, Beaux-Arts edifice that would cater to wealthy tourists and impress potential investors. By the time he secured funding, however, the design had morphed into a Spanish Colonial idiom that incorporated California’s Native American, Mexican, and Spanish heritages. This formulaic exoticism was harnessed by California’s leisure and real estate industries in the late nineteenth century and used to lure East Coast and Midwestern tourists and settlers to southern California.

In 1902, Miller secured financing from Henry E. Huntington, owner of the Pacific Electric Company, and after considering a few designs for his new hotel, retained the services of architect Arthur Burnett Benton. Illinois-born Benton had moved to Los Angeles in 1891 and went into partnership with William C. Aiken. Most of Benton’s work in this period was residential and heavily influenced by the Queen Anne and Shingle styles then popular on the East Coast. Benton’s oeuvre shifted to an Arts and Crafts idiom after becoming friends with luminary Charles Fletcher Lummis, who advocated via contemporary design journals the Mission Revival as an indigenous Californian architectural style. In 1895, Benton (with Lummis and fellow architect Sumner P. Hunt) co-founded the Landmarks Club, which oversaw the restoration of both Mission San Juan Capistrano and Mission San Diego de Alcalá. In 1900, Benton received a commission for the First Church of Christian Science (1901) in Riverside, which he designed in a faithful Mission Revival style: its whitewashed walls are punctuated by arched openings and capped in red-tiled roofs, an arcade runs along the northwest elevation, and a corner bell tower with espadañas forms a focal point. It is presumed that this commission, along with Miller’s acquaintance with Lummis, led Miller to retain Benton’s services.

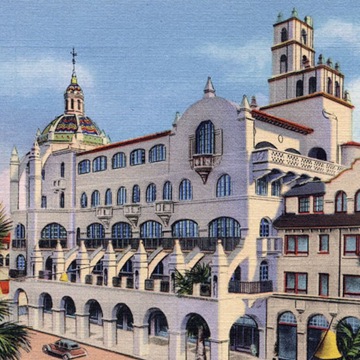

Constructed between 1902 and 1903, the core of Benton’s work is now referred to as the Mission Wing. It is a four-story structure built of brick and stone, and capped with low-profile, red-tile roofs. The U-shaped building faces Seventh Street (renamed Mission Inn Avenue), which is lined with an arcaded wall designed by Benton and added in 1908. The perforated wall has two archways topped with Mission Order gables punctured by espadañas that Benton copied from Mission San Juan Capistrano. Beyond the archways lies a landscaped courtyard, the Court of Birds, which included a bell tower (campanario) loosely designed after that at the Mission San Gabriel, and “Old Adobe,” the first floor of the old Miller family home, repurposed as a tea room. The Glenwood Mission Inn, when it opened on February 20, 1903, boasted an expansive lobby, an elegant dining room, several suites, and 275 rooms on the upper floors. While the hotel was thoroughly modern in its construction methods and materials, promotional literature created by Benton in 1908 portrayed the hotel as a romantic ruin and did not dissuade readers from romanticizing that it was once an actual mission.

Within a decade of its opening, Miller added two wings to the rear (north) of the Mission Wing. Originally known as “The Monastery,” the four-story Cloister Wing (1910) extended north along Orange Street to the northeast corner of Sixth Street. It provided the hotel with additional guest rooms, meeting rooms, and rooftop terraces. Benton derived his design for the Cloister Wing from several sources: the starburst rose window and the domed tower (here five stories instead of two) of the Carmel Mission; the capped buttresses of Mission San Gabriel; and the interior belfries of Mission San Juan Capistrano. The simplicity of the forms and an adherence to precedents places Benton’s Mission Wing in the Arts and Crafts movement, but the Mission Revival style was, ultimately, a historicist idiom that liberally borrowed from other periods and building traditions. Benton’s Cloister Wing thus integrates Moorish, Gothic, and Italianate architectural elements. This pastiche marked a hybrid, transitional style from the plain facades of the Mission Revival, as employed in the Mission Wing, to the Baroque detail characteristic of the Spanish Revival style, as seen in the Spanish Wing (1914). In 1913, Miller retained the services of architects Myron Hunt and Elmer Grey to design this wing in a mélange of the Moorish Revival and Spanish Colonial Revival styles. Spanning the south side of Sixth Street, west of and connected to the Cloister Wing, the Spanish Wing presents the formidable face of a Renaissance palazzo. Constructed of board-formed concrete, the new addition provided luxury suites and meeting rooms as well as rich details, both outside and within, such as the use of tiling, wrought-iron grilles, balconies, sculptured stucco, and decorative plasterwork.

Miller continued to add to his hotel in a piecemeal fashion, and as he traveled around the world he procured architectural salvage (including fountains, fireplace mantels, grilles, tiles, and wooden brackets from the Alhambra) that he incorporated into his growing hotel. In 1925, after traveling to Asia, Miller created the Court of the Orient at the inn, bestowing it with a pagoda tower and Japanese tea garden. In 1928, local architect George Stanley Wilson designed a row of guest rooms in a Neo-Gothic style, housed in a fourth floor added to the Spanish Wing. Wilson also designed the International Rotunda wing in 1931, which featured guest suites, office space, an art gallery, and a wedding chapel also designed in a Neo-Gothic idiom. Finished in 1932, the steel-and-concrete addition is notable for its spiraling atrium stair and for completing the urban block, filling the northwest corner of Sixth and Main streets. It also marked the pinnacle of Miller’s decades-long building campaign. Miller’s hotel had become a fantasy, an amalgam of times and places, and formally, an asymmetrical arrangement of contiguous buildings oriented around open courtyards or enclosed patios with evocative names such as the Spanish Patio or Court of the Fountain. The overall product, reflective of its many additions over the decades, varies in heights (from four to seven stories, including four towers) and massing as well as style.

The Mission Inn has received at least four U.S. Presidents in addition to dignitaries, industrialists, and Hollywood stars. Following Miller’s death in 1935, the inn remained in his family until 1956. The City of Riverside purchased it in 1976 as part of an urban redevelopment scheme to rejuvenate downtown. The city privatized the hotel in 1985 and closed it for a two-year renovation. In 1992, local businessman Duane Roberts purchased the inn and transformed it into a spa resort. Although much of the original material has been compromised, the Mission Inn remains a built manifestation of one developer’s dream, as well as the architectural whimsy characteristic of leisure architecture in the early twentieth century.

References

Benton, Arthur Burnett. The Mission Inn, done by Arthur Burnett Benton, the sketches by Wm. Alexander Sharp…. Los Angeles: Press of Segnogram Publishing Co., 1908.

Fisher, Charles J. “Arthur B. Benton: A Master of the Arts & Crafts Movement.” Echo Park Historical Society. Accessed May 1, 2018. http://historicechopark.org/.

Gellner, Arrol. Red Tile Style: America's Spanish Revival Architecture. New York: Viking Studio, 2002.

Lech, Steve, and Kim Jarrell Johnson. Riverside’s Mission Inn. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006.

McEwen, Emily Ann. “Southern California’s Unique Museum-Hotel: Consuming the Past and Preserving Fantasy at Riverside’s Mission Inn, 1903-2010.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California-Riverside, 2014.

McMillian, Elizabeth. California Colonial: The Spanish and Rancho Revival Styles. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2002.

Pitts, Carolyn, “Mission Inn,” San Bernardino County, California. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1977. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Sagarena, Roberto Lint. “Building California’s Past: Mission Revival Architecture and Regional Identity.” Journal of Urban History 28, no. 4 (May 2002): 429-444.

Weitze, Karen J. “Arthur B. Benton.” In Toward a Simpler Way of Life: The Arts and Crafts Architects of California. Edited by Robert Winter. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Weitze, Karen. California’s Mission Revival. Los Angeles: Hennessey and Ingalls, 1984.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.