The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial is the most recent, though no less controversial, addition to the collection of monuments on the National Mall. It is located between the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials on 1964 Independence Avenue, which references the year the Civil Rights Act became a law. The site selection process was contentious, with African American leaders favoring a site near Constitution Gardens, on the eastern side of the Lincoln Memorial, to highlight King's role as an activist. However, the Commission of Fine Arts, a key federal commission that oversees memorials in Washington, argued the Tidal Basin site was more suited to satisfy spatial requirements. Officially dedicated by President Barack Obama in 2011, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial is the first to honor an African American individual on the National Mall and the first major memorial that does not commemorate a war or a U.S. president.

Congress first authorized the establishment of the memorial in 1996, prompted by Martin Luther King, Jr.'s fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha. Ten years later, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts selected the Tidal Basin as the project site. The Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation held a design competition to select the winning project. A total of 906 artists, historians, and architects from 52 countries entered the contest, submitting three boards each to represent the project idea. The selection panel, made up of architects from the United States, Mexico, China, India, and France narrowed the pool of applicants down to 23 finalists who were asked to submit a fourth elaboration of their idea. In 2000, judges selected ROMA Design Group’s site plan as the winning proposal. ROMA Design Group is a San Francisco-based interdisciplinary design firm specializing in landscape and site design; founded in 1968, it is best known for its revitalization of declining urban districts, including the San Francisco waterfront. In 2007 master sculptor Lei Yixin, who has completed scores of public monuments in his native China, presented his first scale model of the sculpture.

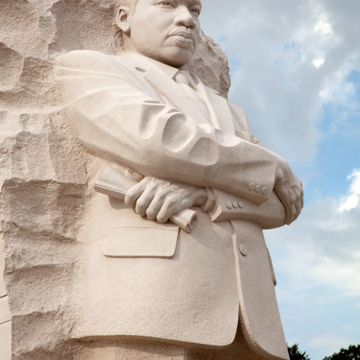

The site plan itself is composed of two distinctive elements: a curvilinear wall that frames and defines the memorial perimeter, and the mountain and King figure, whereby one emerges from the other. This theme references a line from King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech: “With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” King’s specific posture was based on a 1966 photograph of King taken by his photographer Bob Fitch. The mountain is aligned with the curvilinear wall whereas King’s sculpture protrudes significantly forward. Both components feature carefully carved lettering that communicate excerpts from fourteen of King’s greatest speeches. The sculpture and the mountain are composed of 159 blocks of shrimp pink granite, selected by Lei in consultation with the King family. The blocks were transported to Lei’s studio in Changsha, China, where 80 percent of the sculpting took place.

Visitors encounter the memorial by entering it from behind on Independence Avenue or from the front by walking along the Tidal Basin. The 30-foot statue emerges as especially grand, especially when compared to the neighboring statues of Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln, both of which are eleven feet shorter. His raised eyebrow and folded hands suggest a stern body language; Lei aspired to make King appear confrontational and like a “warrior of peace.” In comparison with the other two notable sculptures of great American men, King’s memorial appears to be more approachable. Unlike those of Jefferson or Lincoln, it does not feature pedestals or steps leading viewers to the piece. Visitors can therefore walk around it and even touch it to deepen the connection and experience of the site.

Controversy surrounded the project in regards to the selection of a non-American sculptor and materials, the carving of interpreted comments made by King, and the representational style of the sculpture. First, critics, among them the California chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), raised the question of why the project had to rely on the talents and abilities of a non-American artist. Also concerning were the generalizations that made King’s speeches appear less controversial and universally acceptable. This moved scholars and critics to argue that the memorial made King appear arrogant or suggest the notion that America was a post-racial society; as a result of these discussions, Lei was commissioned in 2013 to modify one of the quotes. Also significant were criticisms of the general style of the sculpture, which recalled Socialist Realist political sculpture, with King taking the pose of a dictator. Others commented that the sculpture does not take enough artistic risks: architectural historian Dell Upton noted that the memorial is one of a series of "great leader monuments" that "demand no uncomfortable thought." Indeed, some scholars have concluded that the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial represents yet another disappointing design process, whereby a project that began as a nonrepresentational abstract work had statuary imposed upon it. Despite these debates, the memorial received an enthusiastic dedication with thousands of people showing up to the celebration.

References

Kevin Bruyneel, “The King’s Body: The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial and the Politics of Collective Memory,” History and Memory 26 (1) (Spring 2014): 75-108.

Patrick Hagopian, "The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial and the Politics of Post-Racialism," History and Memory 32 (2) (Fall/Winter 2020): 36-76.

Nathan King,” Building the Memorial,” National Park Service. Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/.