Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University

Nearly a quarter of a century had passed since W.E.B. Du Bois, American sociologist and civil rights activist, first visited the campus of what was called at the time the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes in Tallahassee, Florida, in 1914. The campus was hardly recognizable to Du Bois. “I was astonished,” he proclaimed, following a return visit in 1939. “From a ramshackle agglomeration of few buildings, few teachers, and indifferent students it has today magnificent buildings and a thousand college students….”

The “magnificent buildings” Du Bois saw likely comprised what is today part of the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University Historic District: a collection of predominantly red brick, Georgian Revival buildings erected on the northeastern part of campus between the years of 1924 and 1940. Together with an earlier, neoclassical Carnegie Library (now the Meek-Eaton Black Archives Research Center and Museum), the buildings form the core of the only state-supported historically Black college in Florida, one of two land-grant institutions in the state, and one of the nation’s more than 100 Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The buildings of the historic district were not the first buildings on the campus, but they were the largest and most central at the time. Today, they mark the architectural identity of one of the most prominent universities in the American South.

What is today referred to as Florida A&M traces its roots to the State Normal College for Colored Students, established in Tallahassee as a teaching college in 1887. At the time, the college found space at the Lincoln Academy, a high school for African Americans, on Copeland Street and Park Avenue (today, the site is incorporated within the Florida State University campus). When the second Morrill Act was passed in 1890, mandating that all existing state land-grant institutions offer race-blind admissions, Florida’s response—similar to other states in the Reconstruction-era South—was to channel its share of federal, land-grant funding towards promoting technical education at an existing African American institution rather than integrating a white state institution. So the State Normal College added “industrial” courses to complement its teaching curriculum and remained at the Lincoln Academy site until its own campus—slightly more than a mile to the south—was prepared to welcome students.

The site was neither new nor insignificant. It was atop Tallahassee’s highest hill—a hill that had once served as the 40-acre antebellum Highwood plantation of former Florida territorial governor William Pope DuVal and his brother. By 1891, DuVal’s estate was owned by absentee landlords; DuVal himself had passed away many years earlier, in 1854. Still, some of the former plantation buildings remained scattered about the spacious and largely rural site. Despite its wistful description by Thomas De Saille Tucker, the college’s first president, as “lovely grounds” with “picturesque scenery” that “have had their marked effect in the making of the institution still more popular with, and attractive to the race for whom it was founded,” the legacy of slavery was deeply embedded in the landscape.

Florida, which became a slave state in 1845, developed a strong economy under DuVal in large part because of slavery. Tallahassee, the state capital, the seat of Leon County, and the center of an enormous cotton industry in nineteenth-century Florida, was also the heart of the region’s slave trade. By 1860, enslaved African Americans comprised 73 percent of the county population. It is likely that DuVal’s plantation contributed to this percentage.

Existing buildings of the former plantation, including DuVal’s mansion and a small handful of barns, were repurposed as academic buildings to establish the new college campus. The mansion served as an “Old Main,” with administrative offices, classrooms, a library, and a dining hall. A few wood-frame structures were built to accommodate a curriculum in agriculture, manual training, music, and teacher instruction, although no nineteenth-century buildings survive on the campus save for the Gibbs Cottage, built originally for Thomas Van Renssalaer Gibbs, the college’s first vice president and former state representative who introduced legislation to establish the institution. Following two relocations, the Gibbs Cottage, completed in 1892, sits today nearly a mile south of the heart of campus.

When instruction began on the former plantation grounds in 1891, African American students were attending school on a landscape that represented—if not directly signaled—racial oppression, separation, and bondage. To experience higher education on the site of a former plantation, and inside some buildings once a part of that plantation, must have made some impact on the African American students of the state’s industrial college in its early years. Some of those students likely were descendants of enslaved persons or sharecroppers.

The plantation mansion only remained for fourteen years on the campus before it burned in a 1905 fire. It was replaced by the Carnegie Library, designed by William A. Edwards in 1907 with an Ionic portico and large pediment. The library set the stage for a new building campaign that would eventually change the look, and the outlook, for the college—although few successive buildings were as rigidly neoclassical as the library. The campaign began under President Nathan Benjamin Young (1901–1923), whose efforts included expanding the liberal arts curriculum to balance the college’s agricultural and mechanical offerings, and continued under President John Robert Edward Lee (1924–1944). Both presidents were instrumental to the college’s growth, though Lee’s legacy may be the more architectural of the two: it was principally under Lee, following devastating fires in 1923 and 1924, when the campus transformed into that which so impressed W.E.B. Du Bois during his 1939 visit.

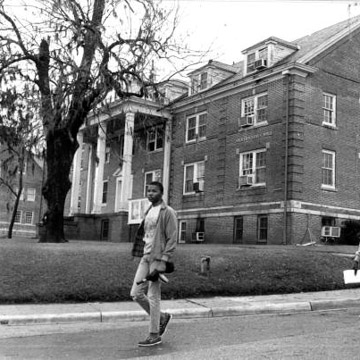

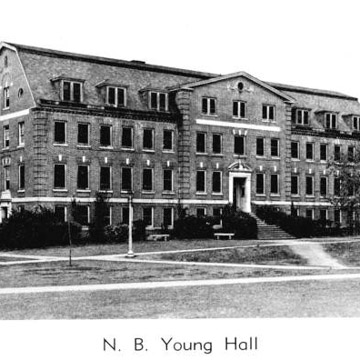

This transformation, which accompanied a rise in enrollment and expanded offerings in home economics, health, music, and professional teacher training also featured the rise of the Georgian Revival, with several buildings designed by Edwards and Rudolph Weaver, architect of the Florida State Board of Control. Many of these buildings were arrayed around open spaces delineated by D.A. Williston’s 1926 “Proposed Plan for Development for the Florida A. & M. College,” which established the central quadrangle of campus. Buildings soon began shaping the quadrangle: University Commons, the new dining hall (1924, Edwards); Lee Hall, the administration-auditorium building (1928, Weaver); and Coleman Library (1946, Weaver). Weaver also designed the residence halls anchoring subsidiary spaces beyond the quadrangle: Jackson Davis Hall, the new women’s dormitory to the southeast, and Nathan B. Young Hall, the new men’s dormitory to the west, completed in 1926 and 1928, respectively. The one-story Lucy Moten Elementary School, built originally as a training school for teachers, was erected a block to the north. These rigidly symmetrical red brick buildings included varying combinations of Georgian Revival elements: end gables, cupolas, dormers, double-hung sash windows, gable and cornice returns, hipped roofs, and classical porticoes.

Weaver brought this Colonial Revival architectural language to the Deep South, oddly, from the Inland Northwest: he had designed a series of buildings, including the Georgian Revival men’s dormitory Stimson Hall at Washington State College in rural Pullman, Washington, where he had worked as the college architect in the early 1920s. Though he also designed several Collegiate Gothic buildings for the University of Florida in Gainesville in the 1920s, Weaver’s Georgian Revival structures at Florida A&M could be seen as providing dignity and refinement to a college focused upon the practical fields of agriculture and mechanics. Such designs may have assumed an additional symbolism in the American South, with its ties to slavery and segregation: Colonial Revival styles were not uncommon for plantation houses throughout the region. “Education in good buildings,” Florida state senator William C. Hodges stated in 1928 at the dedication of Lee Hall, Florida A&M’s principal administration building, “brings better understanding and better fellowship between the races.” Did it?

Red brick, Georgian Revival buildings would continue to mark the campus beyond the World War II years, even if exterior building details became less ornate. This was the case with the new dormitories of J.T. Diamond Hall (1946, Guy C. Fulton), Lula B. Cropper Hall (1948, L. Phillips Clark and Associates), and Phyllis Wheatley Hall (1947, L. Phillips Clark and Associates); and it was the case with the Foote-Hillyer Administrative Center (1949, Yonge and Hart with James Gamble Rogers II)—the original Florida A&M College Hospital and the first to serve African Americans in the state. The campus built environment also expanded well beyond its central spaces in the postwar years, especially with the addition of its law, pharmacy, and graduate schools in the early 1950s. The college was officially renamed the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University in 1953 and opened admissions to all races in 1965.

Additions to campus since the mid-twentieth century have mostly occurred away from the central core and have been characterized by new facilities for journalism, business, engineering, architecture, athletics, and housing, while the central area has received few additions save for new landscaping, pathways, and sculpture. A historic marker in front of Lee Hall recognizes the university’s site on a former slave plantation and its land-grant heritage that emerged from the second Morrill Act. The campus was placed on the National Register in 1996 based on the “school’s significance and the architectural style of its buildings.” The school’s significance is indubitable. Only time will tell whether that architectural style—the Georgian Revival—will continue to be held in equally high esteem.

References

Denham, James M. “‘Florida Founder’ DuVal Played Role in National Issues.” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), June 8, 2017.

Eaton, James N., Sharyn Thompson, Gwendolyn Waldorf, and Robert O. Jones, “Florida Agricultural & Mechanical Historic District.” Leon County, Florida. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1996. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Ensley, Gerald. “Little Known History: FAMU Founded on FSU Campus.” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), May 27, 2017.

Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Florida. Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State. New York: Oxford University Press, 1951.

McDonogh, Gary W., ed. The Florida Negro: A Federal Writers’ Project Legacy. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993.

Neyland, Leedell W. “Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University: A Centennial History, 1887-1987.” Rev. ed. Tallahassee: The Florida A&M University Foundation, 1987.

Nichols, Russell. “Plantation FAMU: University’s Origin Remains Unknown to Many Students.” The Famuan (Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL), February 2, 2004.

Rivers, Larry E. “Slavery in Microcosm: Leon County, Florida, 1824 to 1860." The Journal of Negro History 66, no. 3 (Autumn, 1981): 235-245.

Rivers, Larry Eugene, and Canter Brown, Jr. “A Monument to the Progress of the Race: The Intellectual and Political Origins of the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, 1865–1887.” Florida Historical Quarterly 85, no. 1 (Summer 2006): 1-41.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.