You are here

The Temple

The Temple is the third worship building of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, a society founded in Atlanta in 1860. A permanent place of worship, built in 1875–1877 on Garnett and Forsyth streets, housed the congregation until 1902 when they moved to a second site on Pryor and Richardson streets near present-day Turner Field. Philip Shutze designed the third Temple, a successful amalgamation of Jewish and American symbolism and traditional forms. The Temple is set back on a hill fronting Atlanta’s premier avenue, Peachtree Street.

Numerous classical references and motifs are evidenced in the exterior forms of the monumental building overlooking Peachtree Street, particularly the repeated circular forms that symbolize unity and by extension social justice, so central to the character of this congregation. A temple front of four Ionic columns and unadorned pediment accommodates three entries, the central one under a semicircular portico with a tripartite lunette above. On the roof is a raised circular drum with round-headed windows that is surrounded by a Roman Doric colonnade supporting a shallow dome. The sanctuary below is a breathtaking open volume under an interior dome that appears to float effortlessly above worshipers like a white shroud or weightless canvas sheltering the Arc of the Covenant. Both entry porch and rooftop superstructure call to mind Greek tholos forms, round buildings of uncertain function thought to be either temples dedicated to a local god or hero, or treasuries to store important statues. Here, the tholos is both temple and repository of the Torah scrolls. Crowning the entry porch is an enframed shell with the Ten Commandments.

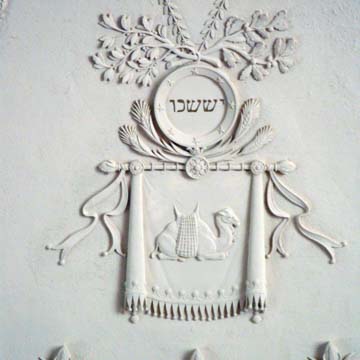

Recalling King’s Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem, the Temple’s foyer with its Star of David embedded in terrazzo flooring represents Solomon’s outer courts, the worship hall represents inner courts, and the procession eventually leads to the raised bimah and golden ark containing the Temple’s Torah scrolls. The ceilings and walls of the Temple are ornamented with Jewish symbols, notably the frieze around the base of the central dome representing the twelve tribes of Israel, with symbols taken from Jacob’s blessings to his sons (Genesis 49). The four corner spandrels of the dome each contains a basket representing the seasonal cycles: flowers (spring), grains (summer), fruits (autumn), and pines (winter). Six carved medallions, in a repeated pattern around the ceiling, adorn a continuous frieze: David’s Harp, symbolizing music played in Jerusalem’s temple; the Chuppah, or canopy, held over the heads of a couple during the wedding ceremony; hands forming the priestly blessing, “The Lord Bless Thee and Keep Thee” (Numbers 6:24); a representation of the Temple’s front exterior; an oil lamp representing the Ner Tamid, or eternal light, found in Jewish sanctuaries, such as that hanging above the pulpit of the Temple and symbolizing God’s eternal presence; and finally, the Tefillin, the phylacteries worn during morning worship services. The Ner Tamid lamp was brought to the Temple from the congregation’s first building and hangs from a chain brought here from the second building. The lamp hangs from an American eagle, connecting Jewish tradition with the American tradition of religious freedom. At every place the aspiring eye comes to rest, a motif, a symbol, or an architectural emblem serves a didactic purpose.

In addition to the notable carvings and plasterwork evidenced throughout the worship space, Shutze’s associates and craftsmen enriched other features of the Temple. Athos Menaboni painted the brown scagliola columns crowned by Ionic capitals, which form a semicircular space that houses the gold-leaf Ark of the Covenant. The curtains behind suggest the tent fabric that historically surrounded the ancient covenant. The prevailing white throughout the space—on walls and in the hovering dome—creates a calm and peaceful environment in which to worship.

The early history of the Temple was marked by vacillations between Reform Judaism and traditional observances. Rabbi David Marx led the congregation for half a century after 1895, influencing a Reform Judaism whose liberalism served to maintain a balance between the city’s Jewish and gentile communities. After World War II, as differing views on social issues, civil rights, and race relations were intensifying the gulf separating certain white groups and advocates of social justice, Jewish leaders such as Marx’s successor, Rabbi Jacob Rothschild, found themselves at odds with extremists in the wider community. On October 12, 1958, fifty sticks of dynamite were set off at the Temple’s north door by white supremacists calling themselves the “Confederate Underground.” The perpetrators, angered by the continuing support of civil rights voiced by Jewish leaders, especially targeted Rabbi Rothschild, who continually criticized segregation and advocated for racial equality. Damage was estimated at $100,000 (the equivalent of over $880,000 in 2019). In addition to executing repairs after the explosion, architects Finch Alexander Barnes Rothschild and Pascal (FABRAP) expanded the temple with the addition of an education building and Freedom Hall.

The most substantial expansion took place in 2002–2004 following designs by Stanley Daniels of Jova/Daniels/Busby. Daniels built a new Covenant Chapel, whose curving ceiling and other design elements evoked tents used by the Jewish people during their period of wandering in the desert. Schwartz-Goldstein Hall, with its 164-space parking deck, is a 7,000-square-foot ballroom and social hall that replaced the former social center named Friendship Hall. The Temple continues to serve a vibrant Jewish community and remains one of Shutze’s best known works.

References

Dowling, Elizabeth Meredith. American Classicist: The Architecture of Philip Trammell Shutze. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1989.

Reed, Henry Hope. “America’s Greatest Living Classical Architect: Philip Trammell Shutze of Atlanta, Georgia.” In Classical America IV, edited by William A. Coles. New York: W. W Norton and Company, 1977.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.