You are here

Sibley Mill

Augusta, located at the head of the Savannah River, has served as an entrepôt since the city’s founding in 1736. The seven-mile Augusta Canal, following a route surveyed in 1844 by railroad engineer John Edgar Thompson, was begun in 1845 and extended from a point above the rapids of the Savannah River into Augusta itself; it was completed in 1847. At the start of the Civil War, both the canal and Augusta’s rail system, together with the city’s inland site, prompted Colonel George Washington Rains to site the Confederate Powder Works in Augusta, which would provide Southern soldiers with gunpowder to fight the war. It is the only permanent structure commissioned by the Confederate States of America.

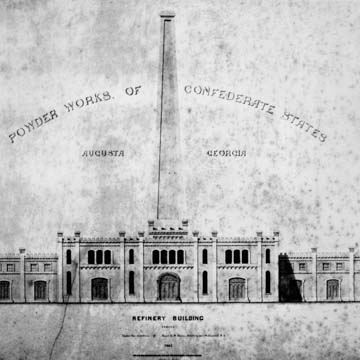

Major Charles Shaler Smith was appointed architect for the complex of twenty-six buildings stretched along two miles of the canal. Widely spaced in order to avoid transfer of fire and chain reaction explosions, the buildings housed an operation that foreshadowed Henry Ford’s assembly line, wherein raw materials (charcoal, saltpeter, and sulfur) entered one end the complex and the finished product (some 2.75 million pounds of gunpowder) emerged at the other end. Construction began in 1861 and, with some borrowed equipment from Atlanta, gunpowder was already being produced after seven months. The Confederate Powder Works was soon the second largest gunpowder factory in the world. Other parts of the Augusta Canal complex produced a wide range of munitions to serve the Southern cause during the Civil War. The massing and crenellated profiles of the main refinery buildings dressed the industrial buildings in an eclectic neo-Gothic imagery.

In August 1864, a violent explosion destroyed part of the factory complex. Although the factory continued to produce gunpowder until the end of the war, the facility was shut down in 1865, after the federal government took it over on the grounds that the property on which it was built had been assigned to the U.S. Arsenal at Augusta prior to the war. The government sold off the land, and in 1872–1875 the remaining factory buildings were destroyed to accommodate the widening of the canal, which was intended to alleviate flooding and also promote industrial development. The impressive obelisk chimney, which rises some 150–168 feet (accounts vary), was preserved as a Confederate memorial.

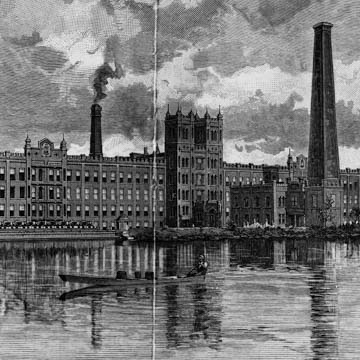

From the ruins of this demolished Confederate complex, however, rose a postwar development that embodied the spirit of what Atlanta journalist Henry Grady called a New South, one helped by northern investment and founded on a development of industry. Augusta’s Enterprise Mill opened in 1878, and two years later the Sibley Manufacturing Company was chartered and would soon rise on the broad footprint of the old factory. The superintendent and architect of the Enterprise Mill, Jones S. Davis, designed a 528-foot-long factory on three floors containing 24,000 spindles for the production of textiles. In 1880–1882, a fourth floor was added. The facility also included 30 tenement houses for mill workers.

Sibley Mill presents a spectacular architectural landmark lining the Augusta Canal and punctuated by the dramatic tower of the Confederate Powder Works. Featuring crenellations, facade frontispieces that extend above the roofline, turrets and pinnacles, the Sibley family coat-of-arms, and a monumental Tudor entry, the mill was intended to be stylish as well as functional. Its picturesque quality and more explicit historicism sets it apart from similar industrial complexes. Extensive ranges of segmental arched windows opened the facade in remarkable ways and illuminated the interior. By the early twenty-first century, these windows were bricked in but the articulation of the building form remains. While the neo-Gothic styling recalls the detailing and profiles of the earlier Confederate Powder Works (indeed, half a million bricks from the demolished factory were used in the mill’s construction), the Sibley Mill may also have been influenced by Augusta’s Richmond Academy, which had been remodeled in the Gothic fashion in the 1850s.

Sibley Mill was built on an unprecedented scale and stood as a symbol of the city’s postwar development. The factory expanded to 35,136 spindles and 672 looms in 1884, and to 40,250 spindles and 1,109 looms by 1895, increasing the mill’s cotton production from over 2 million pounds of cotton in 1883 to over 8.5 million pounds in 1894. However, early-twentieth-century economic decline resulted in production below capacity as early as 1911. Graniteville Company took control of the mill in 1921 and acquired it outright by 1940. Company-owned housing units were all sold by 1969. In the late 1970s, Sibley Mill produced denim for Levi-Strauss using only 32,700 spindles and 634 looms (fewer than in 1884). Even that scaled-down operation ceased entirely in 2006. All processing equipment was removed from the factory, although its water-driven turbines continued to generate electricity for the Georgia Power Company.

Despite this gradual decline, during the last quarter of the twentieth century the Augusta Canal was recognized as the oldest continuously operating hydropower canal in the nation. The Augusta Canal Industrial District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971 and named a National Historic Landmark in 1977. In 1996, the Augusta Canal was declared a National Heritage Area—the first such designation in Georgia. Today, the Augusta Canal area is a city park with the old mule towpaths converted to a hiking and bicycle trail. The nearby Harrisburg district still preserves some of the mill village architecture, ranging from shotgun houses to cottages to two-story brick tenements—a residential type rare in the South. A distinctive recessed entry door, called the “Augusta door,” featuring angled side and top door casings framed with moldings, has been documented in the late Victorian local houses.

The Augusta Canal Authority, chartered by the State of Georgia in 1989, purchased the Sibley Mill in 2010, and sponsored a brownfield clean-up of the site in order to ready it for redevelopment. In 2016, Cape Augusta Digital Properties established Augusta Cyberworks, a mixed-use development that will include offices, apartments, and a data center intended to power the city’s growing tech industry.

References

Cline, Damon. “Augusta Cyberworks hopes to usher in new industrial revolution.” Augusta Chronicle, April 14, 2018.

Curtis, Debra A., “Harrisburg-West End Historic District,” Richmond County, Georgia. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1990. National Park Service: U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Haltermann, Bryan M. From City to Countryside: A Guidebook to the Landmarks of Augusta, Georgia. Augusta, GA: Lamar Press and Historic Augusta Inc., 1997.

“History.” Augusta Canal National Heritage Area. Accessed August 14, 2019. http://augustacanal.com/.

Jorgensen, Robert C., “Sibley Manufacturing Company,” Richmond County, Georgia. Historic American Engineering Record, 1977. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HAER GA-19).

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.