Franklin, a small rural town on the border of Idaho and Utah, is the oldest permanent white settlement in the State of Idaho. Franklin exemplifies the town planning principles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and the more local settlement pattern in Cache Valley. As a base of operations for other pioneers, Franklin was responsible for much of the settlement of southeastern Idaho.

The history of Franklin is intertwined with the larger movement of settlement by Mormon pioneers, who arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 under the leadership of Brigham Young. These Mormons participated in Young’s massive colonization project of the Great Basin and had established ninety-six settlements within a decade, all of them directed by the central authority of the LDS Church. Each settlement began with preliminary exploration companies followed by colonizing companies appointed, supplied, and supported by the Church. Companies modeled their settlements and institutions on Salt Lake City, which was derived from Church founder Joseph Smith’s “Plat of Zion,” also the model for the town plan of previous Mormon settlements such as Nauvoo, Illinois.

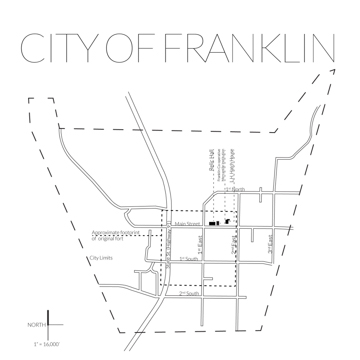

Spurred by a drought in the Salt Lake Valley, Mormons explored Cache Valley to the north where the relative abundance of fresh water led to colonization, beginning with the experimental settlement of Wellsville in 1856. In the spring of 1860 two groups of settlers arrived in northern Cache Valley and founded Franklin, named after Franklin D. Richards, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the LDS. Settlers arranged their wagon boxes into a rudimentary fort, serving as a temporary shelter and defense from Indigenous Shoshone-Bannocks. This pattern became the footprint of the initial arrangement of houses. By the fall of 1860, sixty families had settled in Franklin. Not realizing that they were north of Utah Territory, the pioneers inadvertently created the first permanent European American settlement in what would become the State of Idaho thirty years later.

By 1863, pioneers had built ninety-six cabins arranged end-to-end, enclosing a rectangular area of approximately 1,000 by 1,500 feet that collectively formed a fort. Cabins faced the interior where pioneers built their bowery, a multipurpose worship and meeting hall, and a school.

Shoshone inhabitants of Cache Valley challenged the settlement because Franklin was built on Shoshone trails and camping grounds. Occasionally this led to conflict. Open hostilities were avoided until 1863 when Colonel Patrick Connor and 400 U.S. troops arrived from Fort Douglas and killed approximately 250 Shoshone men, women, and children twelve miles north of Franklin in what is known as the Bear River Massacre. Although non-Mormon miners and others traveling through the valley may have escalated tensions, Mormon settlement in the traditional hunting ground for Northwestern Shoshone contributed to widespread Shoshone starvation, undoubtedly sparking or exacerbating conflict.

After the massacre, Franklin residents did not regard surviving Shoshone people—some of whom joined the LDS Church and eventually assimilated—as a threat and they began moving out of the fort. A village was planned following the Mormon Plat of Zion: a cardinal grid of wide streets and 10-acre blocks, each subdivided into eight lots. In the spring of 1864, pioneer families moved onto 1.25 acre lots allocated by drawing numbers. One of the lots went to John and Ann Doney, who emigrated from England and walked from Boston to Salt Lake City as part of a handcart train, arriving with the first group of Franklin settlers in 1860. The 1864 stone and adobe house that John and Anne Doney built is one of the oldest mortared stone houses in the state.

While other Mormon settlements in the area were ethnic enclaves, Franklin’s residents came from diverse parts of Britain and Scandinavia, which directly affected its architecture. In 1872 stone masons from England used locally quarried stone to build one of the finest surviving Greek Revival houses in Idaho, home to Lorenzo Hill Hatch, the first mayor and second bishop of Franklin. Mormons cultivated their taste for Greek Revival in upstate New York, where the style was in vogue when they began their trek across the American West. With its gable front, ashlar stone walls, stone quoins, denticulated eaves, and gable returns, the Hatch House is a classic example of a Greek Revival temple-form plan house. The facade is articulated by three bays of openings on the first two floors and a single window in the attic. Franklin’s largest residence at the time of its completion, the house was occupied by Hatch’s descendants until the 1940s; it was acquired by the Idaho State Historical Society in 1979.

Over time, Mormon settlers began to demand imported goods, threatening the LDS Church’s longstanding policy of self-reliance. In 1868 church leaders established Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI) to compete with outside goods and the following year added a network of cooperative general stores including the 1869 Franklin Cooperative Mercantile Institution (FCMI). The two-story, gabled-roof FCMI is an early example of Mormon pioneer stone craftsmanship. River boulders serve as the foundation for rusticated ashlar walls of the facade and dressed stone rear and side walls. The symmetrical facade has a central paneled door and transom with windows on either side and two windows above. Rusticated quoins frame the facade, and stone coping crowns the curvilinear false front that obscures the gable roof.

As Franklin grew into an established town at the northernmost edge of Zion, it served as a base for settling the newly organized Idaho Territory. From Franklin, the Church directed the settlement of nearby towns such as Oxford, Mapleton, and Riverdale and later as the base for colonizing Paris, Bennington, Bloomington, Fish Haven, Liberty, Montpelier, and Ovid in the Bear Lake Valley. Mormons ultimately colonized sixteen villages in Idaho, earning Franklin its distinction as the mother of settlements.

Given its location, Franklin was caught between the authority of the LDS Church, the Utah territorial government, and the Idaho territorial government. Although a federal boundary survey placed Franklin geographically in Idaho in 1872, it remained culturally tethered to Salt Lake City. The completion of the Deseret Telegraph line in 1868 strengthened this relationship, as did the construction of the Utah and Northern Railway, a narrow gauge rail spur that terminated in Franklin in 1874 and facilitated the town’s role as a business center. Franklin grew rapidly in wealth and population and by 1890 its census population peaked at 1,330.

Though the railroad’s northern extension eventually shifted the center of government, institutions, and economic output north of Franklin, the decline of the town’s commercial importance did not lessen its legacy on the development of southeastern Idaho. In 1910, Governor James Brady proclaimed June 15 as Idaho Day to honor Franklin and its pioneers; that year people held a large celebration for the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Franklin. Now celebrated on the last Saturday in June, “Idaho Days” endures as an important commemoration for Franklin’s residents.

The heightened interest in celebrating pioneer heritage spurred the creation of a Relic Hall, brainchild of Elliot Butterworth, who gathered items to commemorate lives of pioneer settlers. In 1923 Franklin residents purchased the old FCMI building to house the collection. It soon proved to be too small and by the 1930s, plans were underway for a new building. In 1935 architect Chris Gunderson designed a Rustic-style building, with a mortared river cobble foundation, walls of peeled logs with mitered corners, and a broad wood-shingled roof supported by exposed king-post trusses connected with X-bracing. The Works Progress Administration oversaw construction with labor supplied by the Civilian Conservation Corps and logs and lumber furnished by the Forest Service. The LDS Church donated the land to the Idaho Pioneer Association, which, in turn, deeded it to the state. Overseen by the Works Progress Administration, with labor supplied by the Civilian Conservation Corps and logs and lumber furnished by the Forest Service, the Relic Hall is a prime example of Depression Era Rustic architecture. It was completed in 1937 and its opening was celebrated with speeches by Governor Barzilla Clark and a founding pioneer, Ann Chadwick Hull.

Although Franklin is still a small town of fewer than a thousand residents, its legacy outweighs its size. Franklin was key to centralized colonization by the Mormons, who used it as a base of operations for swift and efficient settlement. As such, Franklin was the genesis of considerable development in southeastern Idaho today.

References

Arrington, Leonard J. "Colonizing the Great Basin.” Ensign10 (February 1980): 18-22.

Attebery, Jennifer Eastman. Building Idaho: An Architectural History. Moscow: University of Idaho Press, 1991.

Attebery, Jennifer Eastman, “Franklin Co-operative Mercantile Institution,” Franklin County, Idaho. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1991. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. http://history.idaho.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/Franklin_Co-operative_Mercantile_Institution_91001717.pdf.

Bennett, Eldon. “An Early History of Franklin.” City of Franklin. January 1, 2004. Accessed April 13, 2015. http://franklinidaho.org/franklins-history.html.

Coates, Lawrence G., Peter G. Boag, Ronald L. Hatzenbuehler, and Merwin R. Swanson. “The Mormon Settlement of Southeastern Idaho, 1845-1900.” Journal of Mormon History20, no. 2 (1994): 45-62. Accessed March 12, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23286599.

Hamilton, C. M. Nineteenth-Century Mormon Architecture and City Planning. Cary, NC: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Hart, Arthur A., “L. H. Hatch House,” Franklin County, Idaho. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1973. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. http://history.idaho.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/Hatch_L.H._House_73000684.pdf

Idaho Pioneer Association. A Brief History of Franklin: First Permanent Settlement in the State of Idaho. Franklin, ID: Idaho Pioneer Association, 1960.

Idaho State Historical Society. “Franklin Cooperative Mercantile Institution.” Accessed April 14, 2015. http://history.idaho.gov/franklin-cooperative-mercantile-building.

Idaho State Historical Society. “An Important Piece of Franklin’s History.” Accessed April 14, 2015. http://history.idaho.gov/hatch-house-and-doney-house-0.

Idaho State Historical Society. “Relic Hall.” Accessed April 14, 2015. http://history.idaho.gov/relic-hall.

Kovach, Milan, and Tricia Canaday, “Relic Hall,” Franklin County, Idaho. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 2000. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. http://history.idaho.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/Relic_Hall_00001627.pdf.

Ricks, Joel E. The History of a Valley: Cache Valley, Utah-Idaho. Logan, UT: Cache Valley Centennial Commission, 1956.

Robinson, O. D. The Oneida Stake: 100 Years of LDS History in Southeast Idaho. Preston, ID: Preston Citizen, 1987.

Young, James Ira. “The History and Development of Franklin, Idaho during the Period 1860-1900.” Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1949.