The United Airlines Terminal at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, completed in 1988, was the first major addition to the airport since its first commercial passenger flights took off in 1955.

Planned to address the overcrowding at Midway, the existing airport landlocked on Chicago’s south side, O’Hare Airport was built seventeen miles northwest of the loop on the site of a manufacturing facility that produced Douglas C-54s during World War II. Originally called Orchard Field, it was renamed for Navy Flying ace Edward O’Hare in 1949. Planning for the airport began in 1945 and was completed in 1948, largely as designed by engineer Ralph H. Burke. Even as city officials gathered funding and persuaded airlines to move from Midway—while also working on the construction of a new highway to connect O’Hare to downtown Chicago, the introduction of jet airliners necessitated acquiring additional land in order to lengthen the original runways.

C. F. Murphy Associates was given the task of creating a modern airport configuration suited to jet airplanes. Their master plan proposal included five, two-story terminals with arrivals and departures on different levels and administrative functions housed on a mezzanine floor. The terminals were to be arranged around a half-hexagon with parking in the middle. Three terminals and the original parking deck were built according to this plan. The terminals were long, steel-framed glass boxes connected by glass bridges with a circular restaurant building at the junction between terminals 2 and 3. The original O’Hare terminals, all unmistakably Miesian in character, were soon were filled to capacity.

Even before O’Hare’s official dedication in 1963, nearly 20 million passengers a year were using the airport, far exceeding the original traffic projections. This number grew by 10 million every decade through the 1990s, forcing the city to undertake a series of additions and expansions starting in the 1970s. As part of the City of Chicago’s O’Hare Airport Development Plan of 1982–1985, the United Airlines Terminal 1 for United Airlines became the first major addition to the terminal areas. The firm responsible for the design of Terminal 1 was Murphy/Jahn, headed by Helmut Jahn, who had begun working for C.F. Murphy Associates after studying at Illinois Institute of Technology and who took sole control of the firm in 1981.

Once air travel became an essential part of the nation’s transportation system, architects began experimenting with various layouts, trying to achieve the most efficient and effective results. At Dulles Airport, Eero Saarinen designed a central terminal with shuttles to transport passengers to the gates. At Dallas-Fort Worth the plan was decentralized, creating long distances between the different sections of the airport. At O’Hare, Murphy/Jahn tried a different strategy. The plan for the United Terminal uses two long, parallel concourses that are connected underground by an 860-foot tunnel. The terminal is long, providing plenty of automobile access, and it retains the two-story departure/arrival paradigm of the earlier O’Hare plan.

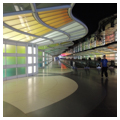

The United Terminal is built of steel, but the girders arch over the concourses as a soaring framework that is lightened visually and structurally by circular cut-outs. In the main concourses the tall central arch reads like the nave of a great glass cathedral. The glass exterior bathes the interior in light, although shades are built into the structure to provide relief from the light and heat. The color palette throughout is subtle: the steel frame is primarily white; the terrazzo floors are large black and white squares outlined in a slim band of brilliant red; simple black rectangular signs mark each gate and the elevator doors are all brushed stainless steel.

In the tunnel color takes center stage. The tunnel is approached down a steep bank of escalators or down an adjacent stair, taking you into what appears from above to be a dark, cavernous space. But at the bottom the space opens up before you with color and light. Running down the center of the gray terrazzo floor are two pairs of moving walkways in each direction. Alongside the walkways, the undulating walls display an ever-changing light show that is synchronized to subtle music playing over speakers. Above is a canopy of changing neon lights. The tunnel transforms what could be a mind-numbing passage beneath the airfield into a memorable experience, one that is both entertaining and calming.

After 9/11, the terminal was radically overhauled to accommodate new security screening. Although this has certainly tightened up some of the original spaces, Murphy/Jahn’s design has proved up to the challenge.

References

Jahn, Helmut. Airports. Basel: Birkhauser, 1991.

Miller, Nory. Helmut Jahn. New York: Rizzoli, 1986.

Miller, Ross. “Chicago Architecture after Mies.” Critical Inquiry6, no. 2 (Winter 1979): 271-289.

Royston, Anne. “Chicago O’Hare International Terminal Complex.” In AIA Guide to Chicago, edited by Alice Sinkevitch and Laurie McGovern, 284-289. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Zukowsky, John, and Mark Jansen Bouman, eds. Chicago Architecture and Design 1923-1993: Reconfiguration of an American Metropolis. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1993.