Tremé

Tremé (variously known as the Tremé or Faubourg Tremé) is a neighborhood of New Orleans adjacent the Vieux Carré. While Hurricane Katrina damaged large parts of New Orleans in 2005, Tremé only had moderate flooding. One of the oldest neighborhoods in the city, it dates from the late eighteenth century and its residents have historically been a culturally diverse mix of Creoles, free people of color, and Europeans, all of whom have added significantly to the city’s cultural heritage. From the early nineteenth century onward to the present, for instance, many of the city’s building tradesmen and craftsmen, including builders, brick masons, plasterers, and carpenters, lived and worked here, passing down skills and techniques to succeeding generations. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many early jazz musicians lived here, working bars and clubs in the notorious Storyville district (on adjacent Rampart Street), in the nearby Vieux Carré, along the southern shore of Lake Pontchartrain, and elsewhere in the community. This musical legacy continues, and many contemporary brass bands have emerged from residents and traditions such as those found in Tremé and nearby neighborhoods.

Two historical landscape features associated with Tremé, which represent important economic and cultural histories, remain significant today. The first is the Carondelet Canal (1790s), a shallow canal dug to connect Bayou St. John (and Lake Pontchartrain beyond) with the back end of the Vieux Carré. This canal was a major transportation corridor into the city, first for maritime traffic, then rail. When the wider and deeper New Basin Canal was built uptown in the 1830s, the Carondelet Canal became less important and was eventually infilled in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Various rail lines continued along this corridor until they were all consolidated into the Union Passenger Terminal in 1950s. As early as the mid-1970s, urban planners proposed turning the corridor into a linear park, but this idea gained little public attention until post-Katrina recovery efforts articulated widespread community interests in the enhanced opportunities for recreation, open space, stormwater management, and non-motorized transit. These interests have guided the master plan of the new Lafitte Greenway for pedestrian and bicycle traffic, which opened in 2015.

The second significant landscape feature is Congo Square, a public open space corresponding in size with nearby Jackson Square and located between the Municipal Auditorium and Rampart Street. Originally a cemetery just outside the boundary of the French settlement, this space became a venue where, under laws of the prevailing French colonial Code Noir, those of African descent, free and enslaved, could congregate on Sunday, sing, dance, drum, play games, and sell materials and foodstuffs they had produced. Vivid firsthand descriptions, notably the 1819 account of architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, describe the lively atmosphere and revelry here, documenting the connection between this place and music and giving rise to the notion that it is from this site that African and Caribbean musical rhythms and traditions evolved into jazz. Notably, this was also the first venue for the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival (1970), which has now become a major music festival. Altogether, Congo Square’s history represents the confluence of local social, economic, musical, spatial, agricultural, and leisure-time activities and the importance of this urban space to the city’s multicultural identity.

In the early 1960s a large portion of Tremé adjacent to Congo Square (which, at the time, was known as Beauregard Square, renamed in the late nineteenth century for the Confederate general and native son) was razed in misguided urban renewal efforts for the creation of a cultural complex. Ironically, much of what was destroyed in architectural inventory and the displacement of long-term residents represented truly authentic local culture. At the time, however, there was little appreciation among decision-makers for such cultural heritage. A performing arts center was built (now named for local gospel legend Mahalia Jackson), and, bowing to growing pressure, a few historic buildings were preserved but have not been maintained. A proposal by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, modeled on Copenhagen’s Tivoli and featuring a Ferris wheel, was resoundingly rejected as being inappropriate, but what was eventually built, designed by a local architect, has little relationship to any local context. Congo Square (renovated in the 1970s), Municipal Auditorium, and a new park enclosed with a fence (further alienating the public space from the local neighborhood) became collectively known as Louis Armstrong Park, although there is no connection between this space and the musician, who was born and lived in another part of New Orleans. The National Park Service had a branch in Armstrong Park as part of its urban parks initiative, but funding to develop this site and others nearby as a national park related to jazz and local musicians has repeatedly stalled in Congress.

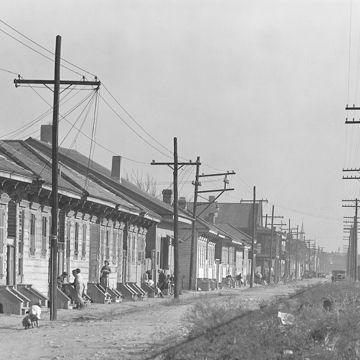

Additionally, in 1969 a six-lane elevated highway (I-10) was constructed along Claiborne Avenue, a primary shopping district and neighborhood space for the community. The avenue was lined with oak trees as well as azalea gardens. Along here were Black businesses including theaters, restaurants, and toy stores, as well as drug stores and insurance companies. The first Black-owned full service grocery, Circle Food Store, was along this avenue. The highway was initially supposed to have been built along the river through the French Quarter, but residents and preservationists fought that plan. The new I-10 not only physically divided the neighborhood but destroyed over 500 residences and businesses along Claiborne. Today Claiborne Avenue remembers the oak trees through painted murals on the highway columns, an act that does little to soften the impact of the structure. There are still calls for removal of the elevated highway.

Post-Katrina, the Tremé neighborhood became widely known from the HBO series (2010-2013) that engaged many local actors, writers, musicians, locations, and neighborhood residents to tell of the city’s recovery. Most locals agree this series, unlike other depictions of New Orleans, accurately captures the rich cultural complexities of this neighborhood, its residents, and their history.

References

Crutcher, Michael E., Jr. Treme: Race and Place in a New Orleans Neighborhood. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

Douglas, Lake. Public Spaces, Private Gardens: A History of Designed Open Spaces in New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.