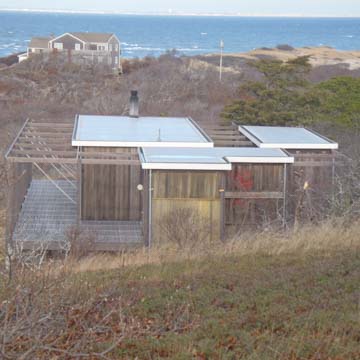

In 1961, self-taught architect, artist, and carpenter John “Jack” Hughes Hall (1913–2003) constructed the Hatch House, an elegant and understated masterpiece of residential design in northwest Wellfleet. In the process, Hall produced a distinct, regional, even vernacular, variation of modern architecture wherein he combined historic precedents with design influences from his modernist architect friends and experimented with new construction methods. The Hatch House respects Cape Cod’s temperamental weather and attends to its hillside location’s sensitive landscape. At the same time, the building, commissioned by New York writer, critic, and editor Robert Hatch, took part in the transformation of this former isolated coastal community into a bustling summer resort for New York intellectuals.

Though the Hatch House falls within the category of modernist architecture, it is more justly understood as a product of Hall’s artistry as well as his relationship with the community and architecture of Cape Cod. Born in 1913 in New York City, Hall hailed from an upper-middle-class family, attended a prestigious boarding school, and graduated from Princeton in 1935 with a degree in English. Never settling on a single career, he experimented with the arts and crafts, including painting, carpentry, and writing. In the late 1930s, Hall moved with his first wife (of an eventual four) to Wellfleet and bought property on Bound Brook Island, now a misnomer because sedimentation has connected it to the mainland. This landscape of undulating dunes, heath, and second-growth pine forests was previously agricultural land and also the home of Lorenzo Dow Baker, the founder of United Fruit and an early champion of the tourist industry in his hometown of Wellfleet.

On Cape Cod, Hall connected with a coterie of American and European intellectuals, architects, and artists who lived in the area both year-round and seasonally. The group catalyzed around the wealthy Boston Brahmin and amateur architect Jack Phillips, a friend of Hall’s who had inherited 800 acres on Wellfleet’s eastern shore in the late 1930s. Phillips designed and built the area’s first modernist house and studio and later introduced to Wellfleet the Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, whom he met while briefly attending Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Through the 1940s and 1950s, intellectual currents from New York, Boston, and Cambridge merged in this former fishing and farming village. The region’s striking, remote environment and its proximity to the artistic community in nearby Provincetown attracted many new architects and artists. Modernist houses emerged throughout Wellfleet’s pitch pine forests. Hall became a staple of this vibrant community whose innovative ideas about design greatly influenced him.

In 1960, Robert Hatch, a prominent theater and arts critic and, later, editor of The Nation, commissioned Hall to design a simple family summer house on Hatch’s newly acquired piece of land on Bound Brook Island, near Hall’s own house. A single dirt road provided access to Hatch’s property, which offered sweeping views of Cape Cod Bay and enjoyed relative isolation. Though Hall had received no formal training, during the 1950s he worked for the design firm of Nardin, Radoczy and Mayen, and the architectural firm George Nelson Associates, becoming steeped in modernist design principles in the process. Hall applied this new knowledge to a few designs around Wellfleet, including his own 1950 house and a local restaurant. Hatch employed Hall to create a modernist dwelling with an unlikely inspiration: a set of old chicken coops converted to beachside vacation huts that Hatch and his family had stayed in during previous visits to Wellfleet.

The design Hall developed in collaboration with a local builder and carpenter, Jean Kaeselau, blended the informality of a camp-like set of huts with a rigorous, modernist design plan. The Hatch House consists of a unique wood-frame, modular structural system that blends indoor and outdoor spaces. Thirty-five nearly cubic modules, each 7 x 7 x 8 feet, sit in a single level on a 35 x 49–foot wooden platform elevated on concrete pilings, which makes the whole building appear to float above the ground. The overarching structure of the house is a geometric exoskeleton consisting of 2 x 4 columns and 2 x 6 beams, all made of fir.

Hall and Kaeselau created interior spaces by attaching panels to the open frame. Within the three-dimensional grid, sets of cubes form three separate but connected rooms. A living space, which occupies ten cubes, contains a bathroom, living room, and kitchen. Three cubes comprise the master suite, which has a bedroom, dressing room, and studio. Two cubes form two adjacent guest/children’s bedrooms. The living room and kitchen have built-in shelving and benches, while a rounded metal wood stove sits in the north end of the living room.

Each unit has a flexible skin. While vertical wood planks sheath some walls, others have a rope and pulley system that raises large, top-hinged plank doors outwards, a feature that not only removes the walls, but also creates awnings over the deck when fully opened. The bay-facing living room wall involves three layers: a handmade mosquito net (nets large enough to cover the openings were not commercially available), sliding Plexiglas doors, and the hinged shutters. The entire house can open and close itself to the environment; it is responsive and malleable.

Open-air hallways connect the room “pods” and offer scenic views towards the bay, dunes, and forest. The underlying deck of these interstitial spaces is porous; Hall left three-quarter-inch gaps between the vertically affixed deck boards in order to accommodate the breeze and dematerialize the deck. Inhabitants crossing between rooms or lounging on the deck can look through to the swirling sands and beach plants below.

The house has no primary or defined facade. Each elevation presents a different asymmetrical arrangement of open and closed cubes. A small staircase in the southeast end of the platform leads into the house, with two open bays serving as an entrance foyer. Along the western (bay-facing) elevation, all of the modules are open to provide a deck from which to view the water and sunset.

Hall and Kaeselau’s masterful creation simultaneously blends into and stands apart from the landscape. The cubic, modular frame starkly contrasts with the dunes’ undulations, yet experienced from within, the building seems to commingle with and disappear into the environment. At the same time, Hall’s design concept looks both forward and backward. The close and deliberate relationship to the environment reflects that of traditional Cape Cod dwellings, which had to contend with the area’s often severe storms and winds. Like these earlier houses, Hall left the Hatch House unpainted and unvarnished. In particular, Hatch House has a close kinship with the dune shacks of Provincetown and Truro. Artists, writers, and others who sought unparalleled solitude, peace, and natural beauty built small, inexpensive seasonal huts in the vast dune landscape that covers the northeasternmost portion of Cape Cod. Typically inhabited only temporarily by their owners, these wooden shacks were small, rustic structures made transient by design, allowing them to be moved as the dunes shifted. The dune shacks sat on pilings reminiscent of those at the Hatch House, and the primitive interior spaces of Hall’s building very much evokes the shacks’ interiors, while the building as a whole also gestures towards the simple chicken coops that originally inspired Hatch.

Yet the Hatch House also signaled major changes in residential architecture for Cape Cod. On a stylistic level, Hall sought to express modernist design principles such as functionality, integration with site, and structural geometry. He strove to simplify and streamline the house’s construction in order to create a reproducible, affordable house plan, exemplified in his use of mass-produced materials like Plexiglas. In this respect, Hall succeeded with the Hatch House, which has an elemental simplicity.

Furthermore, the Hatch House differed significantly from the houses of year-round Cape Cod residents in that it is emphatically and deliberately a summer dwelling. Sitting atop a bluff and lacking insulation, the house offers little protection from the elements during colder seasons. Instead, it opens itself to the milder months’ pleasant breezes and scenic sunsets. Sturdier Cape houses sat in hollows that provided shelter from wind and snow and had massive hearths that projected heat into insulated rooms.

In 1961, the federal government created the Cape Cod National Seashore to protect the region’s invaluable ecosystem that was being threatened by real estate development. Many of the modernist houses of Hall and his colleagues now sit within this protected land. In 1973, the Hatch family sold their house to the National Park Service, but retained 25-year use and occupancy rights. In 1998, the National Park Serve assumed ownership of the house and, in 2010, completed extensive renovations to lease the house to visiting artists. Hall’s modest but notable house endures atop its bucolic bluff as a testament to architectural traditions and innovations, individual creativity, environmental awareness, and the transformation of Cape Cod.

References

Adams, Virginia, Laura Kline, and Jenny Fields, “Ruth and Robert Hatch House,” Barnstable County, Massachusetts. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 2011. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

McMahon, Peter, and Christine Cipriani. Cape Cod Modern: Midcentury Architecture and Community on the Outer Cape. New York: Metropolis Books, 2014.