Situated on the eastern side of the campus of the United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities, the award-wining Bigelow Chapel is a contemporary answer to the needs of a multidenominational community. The seminary represents more than 20 denominations and faith traditions, and prior to the chapel’s construction it did not have a purpose-built worship space. In 2000, the seminary selected the Minneapolis architectural firm, Hammel, Green and Abrahamson (HGA), to complete the project. HGA served as both architect and engineer for the project, finishing work in 2004 for just under $3 million. Principal designers on the project were Joan Soranno and John Cook.

Due to the diverse religious needs implicit in the program, the architects were tasked with creating a neutral and serene space, infused with a sense of spirituality and theology, as then seminary president Wilson Yates stated in Architectural Record: “We wanted the building to suggest a spiritual invitation to worship. It really had to do with the creation of sacred space.” In response, HGA’s architects manipulated scale and light to create a chapel that did not overwhelm the rest of the campus. As Soranno notes, while many traditional religious buildings rely on a monumental scale using darkness to create intimacy, “here we made the scale smaller but flooded the sanctuary with light.”

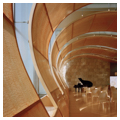

The seminary stipulated that the sanctuary layout be flexible in order to easily accommodate a variety of seating configurations, as dictated by the diverse worship services and other events that would be held there. Additionally, the space had to be accessible iconographically and aesthetically to the multidenominational community. The resulting space comprises a processional corridor that includes rotating displays of art, a narthex, a 2,240-square-foot chapel with seating for up to 200 individuals, and a bell tower—all meant, as one critic observed, “to reflect the mystery and power of God and address the diverse spiritual lives of its multidenominational users.”

The 5,300-square-foot structure needed to enclose the eastern end of the quadrangle and connect with an existing classroom building, as well as complement the modern architecture of the complex, buildings of buff-colored brick and precast concrete completed in 1974 by Cerny Associates. Soranno resolved these challenges through a series of vertical and horizontals. A horizontal cantilevered roof extends over the narthex and west entrance. Glass fins vertically cut through the exterior of the building’s nave. A bell tower rises 40 feet in height on the southern end of the building.

The chapel is clad in 4-foot-square panels of precast-concrete veneer cast by ArtStone of New Ulm, Minnesota. The panels were modeled from real split-face Italian travertine, a material the committee wanted to use to clad the structure but could not afford. The company made fifty different casts of stone facings, using three different colors, of which thirty-nine were usable. They then reproduced them in 4,000 precast-concrete forms and arranged them in patterns of more than 150 diverse facings. The bell tower, consisting of two 40-foot-high, 12-inch-thick walls spaced two feet apart, uses the same material though each wall was cast in place.

To keep the interior space column-free, tapered beams were secured to roof girders through innovative movement connections. This also transferred the majority of the weight to the east wall and off of the glass curtain wall on the west. The “invisible columns” are actually small stainless-steel mullions in the curtain wall. The curtain wall is intersected by translucent glass “fins” that project at 90-degree angles, reflecting the vertical lines in the surrounding buildings while visually diminishing the wall’s length. Each fin is made of two panes of 1/2-inch-thick, low-iron glass with laminate between the two panes. Low-iron glass appears less green in color than other glass, an element important to the chapel’s design. These fins, reminiscent of Gothic buttresses, also aid in the diffusion of light while visually enhancing the intimacy of the space.

In the chapel’s design, Soranno explored what makes space spiritual, concluding that intimacy, warmth, and light were particularly important. The translucent, quilted-maple veneer panels, placed between 1/8-inch-thick acrylic sheets, create an undulating effect along the west-facing, glass-and-stainless-steel curtain wall, underlying a ceiling of skylights. The panels came from a single bigleaf maple grown in the Pacific Northwest, peeled in Germany, and cut into 1/32-inch veneer in Indiana using a process developed by Wilkie Sanderson, a millwork company in Sauk Rapids, Minnesota. Maple floors and rectangular quilted-maple panels extend from the processional hall on the east side of the building into the sanctuary. Specifically chosen for this purpose, the warmth generated by the maple elements creates a peaceful, contemplative enclosure. As sunlight streams through the translucent panels, enriching the interior light, the effect is a further play on the three themes, engulfing the sanctuary with a sense of intimacy, warmth, and light. Lighting was equally important after the sun set, so to generate the same sense of warmth after dark, HGA worked with lighting designer Michael DiBlasi of Schuler and Shook’s Minneapolis office. The light fixtures were placed to blend in with rather than stand out from the architectural features and were chosen for their warmth and ability to diffuse light, providing effects similar to sunlight. In this case, 50W MR16 lamps were mounted to the ceiling on telescoping stems and above the main processional path a 24-volt xenon strip light system was installed.

Through a large window in the southern facade of the building a meditation garden is visible. Designed by Shane Coen of Coen and Partners of Minneapolis, the garden is centered on a thornless Hawthorn tree and the ground is covered with Virginia slate infilled with flowering sedum and wild thyme.

The Bigelow Chapel is alive with intimacy, warmth, and light. This building, recipient of a Minnesota AIA Honor Award for architecture in 2004 and a national award in 2006, demonstrates how contemporary architectural ideas can meet the needs of spiritual traditions in the creation of a sacred space.

References

Donoff, Elizabeth. "Bigelow Chapel, New Brighton, Minnesota.” Architectural Lighting 20, no. 6 (2006): 56-57.

HGA. “Bigelow Chapel.” HGA. Accessed October 16, 2015. http://hga.com/work/bigelow-chapel.

LeFevre, Camille. “Bigelow Chapel: New Brighton, Minnesota.” Architectural Record193, no. 5 (2005): 236.

Staeger, Tony. “Inspired Innovation the Design of the Bigelow Chapel, in New Brighton, Minnesota, Incorporates Multiple Elements That Can All Be Described in the Same Way: Minimal.” Civil Engineering75, no. 7 (2005): 38-45.

United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities. “The Bigelow Chapel: Architecture.” United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities. Accessed October 15, 2015. http://www.unitedseminary.edu/bigelow-chapel/architecture/.

Yates, Wilson. “The Creation of a Chapel.” Arts16, no. 1 (2004): 4-13.