You are here

Bandelier National Monument Civilian Conservation Corps Historic District

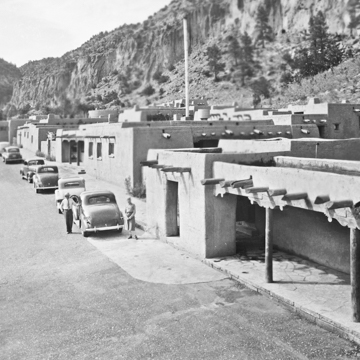

The buildings and landscaping designed by the National Park Service (NPS) for the Bandelier National Monument Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Historic District draw on the Pueblo and Spanish Colonial traditions synthesized in the Spanish-Pueblo, or Santa Fe Style, to create a romantic ensemble in keeping with New Mexico’s image as the Land of Enchantment. The district, which contains 31 largely unaltered buildings, offers a unique opportunity to experience one of the largest and most intact examples of CCC architecture in the nation.

Adolph Bandelier, after whom the monument is named, began archaeological work in Frijoles Canyon in 1880, and by the early 1900s, the significance of its extensive archaeological sites led to efforts to establish it as a national park. Bandelier National Monument was created in 1916, and remained under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Forest Service until 1932, when President Hoover signed it over to the National Park Service.

By 1932, Frijoles Canyon was hosting around 3,200 sightseers a year, but accommodations were limited, and the only way to travel to the bottom and back was by mule. When the Emergency Conservation Work Act was passed in March 1933, the NPS began to make plans to expand access with the help of the Civilian Conservation Corps, newly created by the Roosevelt administration. The CCC provided jobs for young men who worked on a variety of projects, many of them aimed at improving natural resource conservation.

By the end of 1932, Camp No. 815 had been established in Frijoles Canyon, placing around 200 men at the disposal of the National Park Service Branch of Plans and Design. At Bandelier, the members of Camp No. 815 built roads and trails, improved drainage systems, and placed water lines. They constructed and furnished a group of buildings that would house the monument’s administrative and maintenance facilities, as well as provide residences for Park Service employees. In 1937, additional construction began on Frijoles Canyon Lodge, which adjoined the Park Service buildings and offered tourist accommodations.

Working with architects and landscape architects from the NPS Branch of Plans and Design, Lyle Bennett planned the new district and designed most of the buildings constructed between 1933 and 1941; his work for the Park Service included the Painted Desert Inn at Petrified Forest National Monument, and buildings at both Mesa Verde National Park and White Sands National Monument. In 1918, Stephen Mather, the first director of the NPS, had mandated that Park Service buildings harmonize with their environment; following Park Service guidelines, Bennett used both locally-quarried tuff and thick walls, battered profiles, hand-plastered contours, protruding vigas, high parapets, accretive massing, and flat roofs to mimic the architecture of both Native American pueblos and Spanish missions.

In 1934 the CCC completed the first building in the district and by 1937 finished the Park Service administrative, maintenance, and all but one of the residential buildings. The Frey family had been running a lodge in the canyon since 1925, and negotiations with the Park Service led to plans to integrate their business with the district. In 1937, the CCC built a hotel lobby and curio shop, cabins, a dining room and kitchen, a riding stable with chicken coop, a powerhouse, an oil-and-gas house, a garage, employee housing, and a cylindrical utility building, known as “the kiva,” for the Frijoles Canyon Lodge. Flagstone walkways and stone retaining walls connected the buildings around a picturesque courtyard with “the kiva” at its center. Ultimately, the CCC constructed 29 buildings at the bottom of the canyon, as well as a fire lookout tower and an entrance station on U.S. Forest Service land.

Rooms were painted with Pueblo-inspired motifs, and accented with wrought iron handles, along with tinwork light fixtures, mirrors, and switch plates. The CCC also fabricated the architectural woodwork and made all of the Spanish Colonial Revival furniture for the Park Service buildings and Frijoles Canyon Lodge. These pieces were unified by a common style as well as by carved and painted ornamentation using Spanish Colonial and Native American motifs. By the time the CCC departed in 1941, Camp No. 815 had produced over five hundred pieces of furniture and many Hispanic enrollees had gained experience in a craft that would serve to preserve their heritage and provide a means of support in years to come.

This National Park Services site is open to the public during regularly scheduled hours, with shuttle transportation from the White Rock Visitor Center required for park entry between late May and mid October.

References

Gavin, Robin Farwell. “A CCC Legacy for Bandelier: The Furniture of Frijoles Canyon Camp 815.” El Palacio 118, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 52-58.

Harrison, Laura Soullière. “Bandelier C.C.C. Historic District, 1933, Bandelier National Monument.” In Architecture in the Parks: National Historic Landmark Theme Study, 355-382. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1986. Accessed December 15, 2014. http://www.cr.nps.gov/.

Harrison, Laura Soullière, Randall Copeland, and Roger Buck. Historic Structure Report: CCC Buildings, Bandelier National Monument.Denver: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.