Santa Fe embodied the design and planning system characteristic of cities in the Hispanic Monarchy, and these features extended beyond the core portion of the capital city into barrios (wards). As one of the areas that fell directly under the capital’s jurisdiction, the Barrio de San Miguel Analco, just south of central Santa Fe, showcases the city planning conventions that Spaniards envisioned in the Americas. Its church and surrounding ward reveal the hierarchical urban scheme seen in Spanish American cities, which follows the intent of order characteristic of this city system.

The town featured an urban organization with a centralized core and dependent districts, including the Barrio de San Miguel Analco. A cabecera, or head, was the secular or ecclesiastical capital of a region. In Santa Fe, the urban core around the Palace of the Governors and the Church of San Francisco was the city’s cabecera, as the centers of New Mexico’s political and religious institutions resided here. Adjacent connected to the cabecera were barrios like San Miguel, and further away were estancias or clusters of houses. In Santa Fe’s case these estancias were ranchos or huts where farmers or herdsmen lived and carried out their respective activities.

Like the cabecera of Santa Fe, each of its barrios had two central elements: the church and the plaza. Religious, civic, and economic life centered on these interrelated spaces. The Chapel of San Miguel was the first church built shortly after Santa Fe was founded in 1610. Its use was only temporary while the Church of San Francisco in the cabecera was being built. San Miguel was intended to serve as the main place of worship for the Mesoamerican allies and auxiliaries who had arrived with the Spaniards since the earliest expeditions into New Mexico. In fact, the word analco is a word of the Mesoamerican Nahuatl language meaning “on the other side of the river,” referring to the barrio’s location in relationship to central Santa Fe.

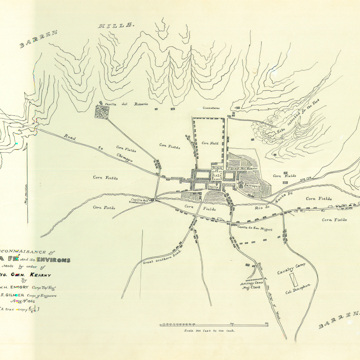

Although there is limited documentary evidence of a plaza accompanying the Chapel of San Miguel, the 1776 Urrutia Map of Santa Fe—the only surviving map of the city in the Spanish period—shows two open spaces in front of the religious structure. A small, adjacent one seems to be the atrio, a walled space reserved for religious rituals. Today the atrio remains but is no longer walled and is now raised slightly above street level. The Urrutia map also shows a larger open space across the atrio. Although it has no labels, the surrounding buildings frame its perimeter in square formation, so it is likely this space was the barrio plaza, where residents interacted and possibly exchanged goods with merchants.

The size and importance of the church and plaza also corresponded with the cabecera-barrio hierarchy. The Urrutia map shows the San Miguel church and plaza as miniscule compared to the San Francisco church and nearby central plaza in downtown Santa Fe because the former is a barrio and the latter a cabecera. Far from uniform, it was partly the unique character of the church and plaza that lent each particular barrio or cabecera its own identity.

This hierarchy of spaces reflects the broader Renaissance perspective that engendered the Spanish City system. Spanish colonization of the New World coincided with the European Renaissance (conventionally dating to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries), a time of revival and reinterpretation of Greco-Roman classical ideas. Consequently, Spanish colonization and urbanism was much inspired by contemporary perspectives on the Greco-Roman past. For instance, the idea to spread Spanish customs, laws, and institutions through foreign cities came from a Spanish reinterpretation of the Roman Imperial model of colonization and expansion, which also used urban centers to spread Roman culture. The prominence of the church-plaza configuration at San Miguel also comes from this time period. In the Renaissance, cities were envisioned, as historian Richard Kagan argues, as “mystical bod[ies]y that incorporated laws, institutions, and customs governing communal life.” Churches and plazas were integral to the realization of this vision, as they provided spaces for the performance of civic and religious processions and ceremonies intended to unite the citizenry. The proclamation of laws and royal decrees, ceremonial parades that acclaimed the king, and major religious festivities took place within these plazas. These open-air events were thus beneficial to the Spanish Crown and its officials because they were able to bring together the different peoples of the Monarchy—Europeans, Native Americans, Africans, and Asians—together under one king and one religion, creating an orderly urban life Renaissance thinkers aspired to achieve.

Spanish cities also exemplified the Renaissance concept of the Ideal City, and, like the utopian plans and paintings that emerged during this period, they shared an ordered and rational system of organizing urban spaces around circular or grid plans to instill clarity, regularity, order, and harmony. In Spanish cities like Santa Fe, the circular layout translates into the cabecera-barrio-estancia system, which can radiate indefinitely. In Santa Fe, the cabecera forms the center of the plan and the Barrio de San Miguel is one of its extensions; the estancias further away from the city were extensions too, as their residents had either religious or civic affiliations to the churches or groups in the cabeceras or barrios. The grid plans helped this radial system extend across the landscape by stretching the street system from a center. The Urrutia map shows how the estancias followed the grid layout from Santa Fe but loosely: the estancia walls are orthogonally oriented to the grid but the houses themselves were not always built to follow street lines.

The grid plan became the model of city planning and design in the Hispanic Monarchy for both practical and symbolic reasons. The straightforward spatial scheme neatly divided space and organized cities and lots, which was convenient for settlers to claim property and for royal officials to keep track of them. But this layout also had Christian associations: the Ideal City was supposed to reflect Heaven on Earth, a place of order amidst a world of chaos. For the missionaries, the grid became the physical embodiment of order in the New World—a place they believed to be chaotic, without Christian morals. The grid thus distinguished an ordered space from a chaotic one, which helped create a sense of unity as well. Those who dwelled in the grid could be seen as unified members of a society, in this case, of the Hispanic Monarchy; they all practiced the same religion, followed the same laws and customs, and lived in similar urban settings.

Even though the grid became a widespread feature in the Hispanic Monarchy, the Spanish settlers were able to adapt it to local conditions, and the Barrio de San Miguel Analco shows that the grid was indeed flexible. Looking at the Urrutia map, the center of Santa Fe has a very clear orthogonal grid, but as one moves farther away from the center of town and south into the Barrio de San Miguel, it becomes more irregular, except for the church plaza. This irregularity is the result of two elements: the Santa Fe River and the roads to Pecos. First, the barrio layout follows the riverbanks, and second, the grid at San Miguel begins to bend once its main streets turn in direction to Pecos, a large trading town where merchants exchanged goods from New Mexico and the Great Plains. Many of those merchants made their way to Santa Fe, so it is likely that San Miguel inhabitants wanted to their barrio to follow the road to Pecos in order to guide the merchants first to their plaza rather than on the main square in Santa Fe.

A closer look at the Barrio de San Miguel Analco ultimately shows how the Spanish city system was a model of radial configuration and expansion during the Hispanic Monarchy. The cabecera-barrio-estancia model and the grid plan allowed Spanish cities to spread across and adapt to different landscapes and settings throughout the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Yet the grid plan was also seen through the eyes of contemporary Renaissance urban theory, which encouraged missionaries to adopt it for its colonization goals and Christian values.

References

Adams, Eleanor B., and Fray Angelico Chavez. The Missions of New Mexico, 1776; a Description, with Other Contemporary Documents. Albuquerque: New Mexico University Press, 1956.

Crouch, Dora P. Spanish City Planning in North America. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982.

Gibson, Charles. The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519–1810. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1964.

Kagan, Richard. Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Kessel, John L. Pueblos, Spaniards, and the Kingdom of New Mexico. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

Rama, Angel. The Lettered City. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

Rautman, Alison E. Constructing Community: The Archaeology of Early Villages in Central New Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2014.

Treib, Marc. “San Miguel.” In Sanctuaries of Spanish New Mexico, 79–88. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.