When the Spanish arrived in New Mexico in the late 1500s, they reached a land that was already home to mostly urbanized Indigenous societies, whom the Spanish collectively named the Pueblo people. Although this civilization was diverse in terms of language, ethnicity, and beliefs, it had a common and rich urban tradition that went as far back as 600 CE, when the first sedentary villages started to appear throughout the Southwest. By the sixteenth century, the region had gone through several phases of town construction, abandonment, and migration, yet the Puebloan building settlements maintained their spatial design for centuries. The Puebloan town of Arroyo Hondo exemplifies these Indigenous building and city planning practices that were in place prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. Surprisingly, many of these urban principles bore affinity to the conventions that Spaniards themselves applied in the design of cities in the Americas. As a result, the existing Pueblo urban conditions in this region facilitated a unique complementary interaction between Indigenous and Spanish urban traditions.

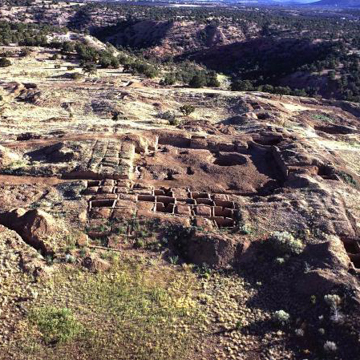

The town of Arroyo Hondo is not too far from the Spanish capital of Santa Fe, just six miles south of the capital at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Yet Arroyo Hondo was not contemporary to the Spanish period; the Puebloan settlement was built in the early 1300s. When a drought in the 1290s caused a decline in harvests, Puebloans started raiding neighboring settlements. These pressures caused many towns to agglomerate into safer, fortified settlements that would be better able to manage resources and organize defense and raiding efforts. Arroyo Hondo was one such town that developed quickly and efficiently to resist the regional pressures due to the drought. Although Arroyo Hondo was a short-lived urban center (it was abandoned by 1425), it became one of the largest settlements in the late Puebloan period, growing ten times its original size within a couple decades. Despite its rapid construction, the settlement displays a planned growth strategy that continued many of the conventions Puebloans had been practicing for centuries.

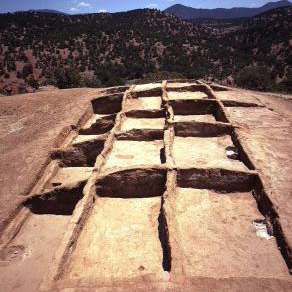

The most apparent of these features is the site’s gridded layout. Twelve hundred two-story attached rooms are all built at a ninety-degree angle from one another, creating twenty-four larger room blocks. The rectilinear wall systems allowed easier expansion of room clusters as kin groups increased in size. The addition of rooms became a common practice in the Southwest, eventually developing into an orthogonal gridded town planning system. Arroyo Hondo is perhaps the apex of this planning practice, as its site design employs one of the most regular and extensive grid plans in the Southwest. As diverse Puebloan groups migrated to Arroyo Hondo and the surrounding area from what is now Northern Arizona and Southern Colorado, the gridded room-block system allowed societal organization in terms of culture, language, and kinship.

This type of urban organization in a time of migration has much in common with the Spaniards and their city planning system. Spanish colonization of the Americas brought people from Africa, the Americas, Asia, and other parts of Europe to what the Spaniards called the New World, and thus, much like the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Puebloan world, the Spaniards needed a system to accommodate migration and settlement of diverse peoples, and they found it in the grid layout, which can be seen in Spanish colonial cities like Santa Fe.

While the grid was a helpful strategy in organizing and ordering a settlement, the diverse, multi-ethnic composition of both Spanish and Puebloan societies motivated them to create a sense of unity within their respective settlements. Centrally located public spaces played an important role in integrating different groups into the creation of a shared culture, as anthropologist Alison Rautman has argued. At Arroyo Hondo the adjacent right-angled positioning of rooms facilitated the creation of open spaces: these thirteen partially or completely enclosed plazas formed the center of domestic and religious life. The latter was especially true of plazas with a kiva, a circular, subterranean room with a flat roof used for religious ritual purposes whose development can be traced to the rise of sedentary villages in the eighth and ninth centuries. It seems that Arroyo Hondo actually grew out from one of these plaza–kiva–room-block complexes (Plaza C) and as the settlement began expanding, a system of secondary plazas and kivas emerged from it. Despite the large number of plazas, a key feature of Arroyo Hondo and other contemporary sites is the diminished number of kivas. Prior to this time period, settlements had multiple kivas, each likely built by different kin or ethnic groups. The fact that Arroyo Hondo has only five suggests that there was more of a concern or desire to create a shared identity. The plazas likely fostered this common sense of belonging and self-awareness, and it was in these public spaces where people cooked, played, and socialized.

Both Puebloan and Hispanic cultures shared many conventions for the design of cities and buildings. Puebloans were the main source of labor in the construction of Spanish buildings, and thus Spanish Colonial architecture in New Mexico reflects much of the Puebloan tradition of highly standardized arrangements of room blocks. Likewise, Spanish buildings like the Palace of the Governors, the seat of political power in Santa Fe, closely resemble a traditional Puebloan structure in both layout and materiality. The Spanish continued the Puebloan architectural tradition of using local materials like sandstone and adobe but also introduced building practices and technologies from Europe. For example, European construction techniques resulted in airier and more vertical spaces in mission churches rather than the traditional small Puebloan rooms. Spaniards also introduced wooden forms to mold adobe bricks, which replaced the traditional hand-molded method. This new practice increased the production of adobe bricks and helped expedite the construction of large projects like churches.

The settlement of Arroyo Hondo demonstrates how the grid, the plaza, and kiva had become common urban and architectural elements in Puebloan settlements. The three play a major role in the planning and design of Arroyo Hondo because their intent was to both provide control in urban growth and create a sense of unity and belonging during a time of social instability and migration. Spanish cities like Santa Fed had much in common with these Puebloan town conventions. They followed a grid plan that featured a network of plazas and religious structures. Much like the Puebloans, Spaniards used these urban and architectural elements to manage growth and to create a shared culture. These similarities facilitated the interaction and cultural exchange of the Puebloan and Spanish urban traditions. The result is a hybrid architecture and urbanism that often follows more European building conventions and typologies, but that ultimately employs traditional Puebloan construction materials and methods that have been used for centuries.

References

Creamer, Winifred. The Architecture of Arroyo Hondo Pueblo, New Mexico. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1993.

Crouch, Dora P. Spanish City Planning in North America. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982.

Kagan, Richard. Urban Images of the Hispanic World, 1493–1793. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Kantner, John. Ancient Puebloan Southwest. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Plog, Stephen. Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1997.

Rautman, Alison E. Constructing Community: The Archaeology of Early Villages in Central New Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2014.

Shapiro, Jason S. A Space Syntax Analysis of Arroyo Hondo Pueblo, New Mexico: Community Formation in the Northern Rio Grande. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 2005.