You are here

New Mexico State Veteran’s Home

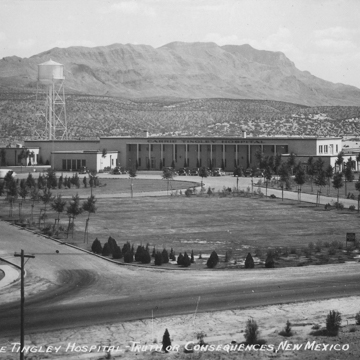

The Carrie Tingley Hospital for Crippled Children is an important example of a specialized modern medical facility—a polio hospital—and of the Territorial Revival Style.

When it opened in 1937, the hospital provided cutting-edge medical care for children afflicted with poliomyelitis and other orthopedic disorders. Before they were made obsolete by the invention of the Salk vaccine in 1952–1955, therapeutic hospitals like this were the most modern response to the polio epidemics that struck (mainly) children during the first half of the twentieth century. The idea for the hospital originated with the Governor of New Mexico, Clyde Tingley (1881–1960), and his wife Carrie (1877–1961), both of whom were known for their charitable work with children. Tingley presented his plans in 1935 at a banquet in Hot Springs (a spa town renamed Truth or Consequences in 1950), and then met with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to discuss the project. Roosevelt, who had contracted polio in 1921 and established the world’s first polio treatment center in 1927 (the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation) was very supportive, writing to Tingley that the hospital was “a matter very close to my heart.” The president recommended that Henry J. Toombs, the architect of the Warm Springs treatment center, consult on the project, and Toombs traveled to Hot Springs on a number of occasions to advise on the building’s design.

In April 1938, Ernie Pyle described Tingley as “probably the money-gettinest man in New Mexico,” and the governor’s style was well suited to the daunting task of constructing a complicated and expensive building project in the midst of the Depression. The hospital was one of nearly 4,000 projects in New Mexico that received funding from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA eventually paid $553,000 of the total cost of $827,000, leaving $273,000 to be financed by New Mexico. Tingley subsidized the project by arranging to have State Penitentiary inmates manufacture 2.75 million bricks at five kilns specially constructed at Hot Springs. He also persuaded the Santa Fe Railroad to reduce freight costs for the project. The Tingleys also contributed personal funds.

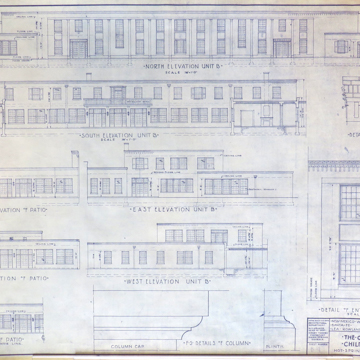

Willard C. Kruger (1910–1986), the head of New Mexico’s WPA Architecture Department, led the hospital design team. Along with John Gaw Meem, Kruger was instrumental in formalizing the Territorial Revival Style, and his use of the style for the hospital is an influential early example of what has remained ever since an idiom of choice for public buildings in New Mexico. Kruger drew on the original Territorial Style, which blended local adobe building practices with imported Greek Revival elements during New Mexico’s Territorial Period. But what had been a fairly modest vernacular in the ninteenth century was now adjusted to suit the monumental scale of a modern institutional building. The hospital’s symmetry, crisp cubical massing, stately entrance portico, and such classical details as the dentiled brick cornices are all characteristic of the style. When completed, the facilities were compared favorably in the press with the treatment center at Warm Springs.

The hospital building originally covered 69,273 square feet (or 1.59 acres). All of the interior spaces were located on the ground floor with the exception of the employee quarters, which were situated above the main entrance on the north side. Patios enclosed by the walls of the building made it possible for every room to face outside. The largest patio contained a fountain with trees, shrubs, and other plantings, and served as an ideal place for sunbathing or “heliotherapy.” An indoor pool looked onto another patio with an outdoor pool.

Three wings provided a total of 100 beds for the patients. Two of these wings housed girls and boys who were convalescing, while the third accommodated patients recovering from surgery. The hospital had two operating suites, X-ray and photographic facilities, a laboratory, a physical therapy unit, cast rooms, a rehabilitation center, and a special education complex. The west end of the hospital contained a brace shop, while the east end included the kitchen and the dining room where the patients were rolled out twice weekly in their beds for movie nights. An adjoining recreation room provided a place for patients to enjoy themselves with tables and games. The hospital also included separate residences for the superintendent and chief surgeon, located across an arroyo to the east.

The hospital’s landscaping has been described as “frontier pastoral.” This adaptation of the “natural” landscapes of the Picturesque Movement to the American West includes two allées leading to the hospital that were lined with poplars and evergreens. Their formality, however, was tempered by plantings irregularly distributed across the manicured lawns. This informality was further accentuated by the hospital’s oblique orientation on the site to accommodate the property’s irregular shape.

The Carrie Tingley Hospital moved to Albuquerque in 1981 and the building in Truth or Consequences reopened in 1985 as the New Mexico State Veteran’s Home.

References

Bermingham, Peter. The New Deal in the Southwest, Arizona, and New Mexico.Tucson: University of Arizona Museum of Art, 1980.

Carrie Tingley Hospital for Crippled Children, Hot Springs, New Mexico: Report, 1939–1941. Hot Springs, NM: The Hospital, 1941.

Carrie Tingley Hospital for Crippled Children, Hot Springs, New Mexico: Report, 1941–1943. Hot Springs, NM: The Hospital, [1944].

Erna Fergusson Papers. University of New Mexico Center for Southwest Research, Albuquerque, NM.

Kammer, David. The Historic and Architectural Resources of the New Deal in New Mexico. Santa Fe: New Mexico Historic Preservation Division, 1994.

Minchew, Kaye L. “Warm Springs." New Georgia Encyclopedia. Last modified October 10, 2013. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/.

Morrow, Baker. “New Deal Landscapes.” New Mexico Magazine 66 (April 1988): 66-72.

New Mexico State Historic Preservation Office. Last modified October 25, 2013.

Pratt, Boyd. “Directory of New Mexico Architects.” With Carleen Lazzell and Chris Wilson. Unpublished draft, last modified October 1988. University of New Mexico Center for Southwest Research, Albuquerque, NM.

Pyle, Ernie. “Tingley Knows his Machines But Has Big Heart for Kids; Governor of New Mexico Admits He’s a Regular Politician Yet He’s Always Doing Something for Somebody and Children’s Hospital’s His Pride.” El Paso Herald Post, April 29, 1938: 5.

Spurlock, William Henry. “Federal Support for the Visual Arts in the State of New Mexico: 1933–1943.” Master's thesis, University of New Mexico, 1974.

U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. “Warm Springs Historic District, Roosevelt’s Little White House State Historic Site, and Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation, Georgia.” Accessed May 2, 2014. http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/presidents/roosevelts_little_white_house.html.

W.C. Kruger Architectural Drawings, c. 1930-1989. University of New Mexico Center for Southwest Research, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.