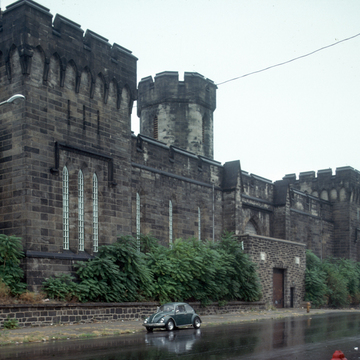

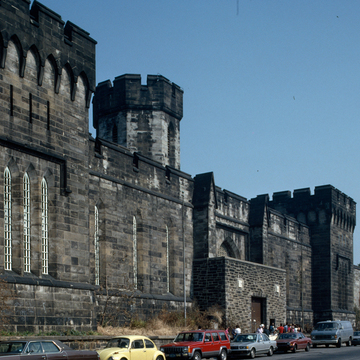

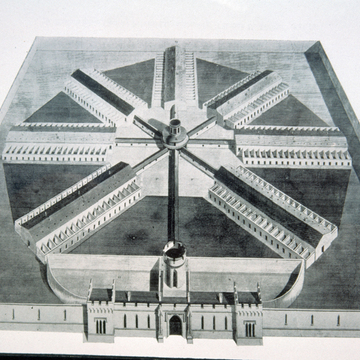

Two early-nineteenth-century landmarks denote the rural nature of the region north of Vine Street before the explosive growth of the industrial city. The site of Eastern State Penitentiary was selected for its isolation and distance from the city—the same motivation for the selection of the site of Girard College ( PH127). The largest and in many ways the most notorious building of preindustrial Philadelphia was this state prison for the eastern district of Pennsylvania. It was built in what was then countryside with the bucolic name Cherry Hill. The 450 cells on a site of eleven acres were constructed at a cost of $780,000, making it one of the most expensive buildings in the nation in its time. Haviland's winning scheme combined the exemplary brutality of the facade of George Dance's Newgate Prison in London with the panopticon utility of Jeremy Bentham's workhouses, making it possible to provide oversight of numerous cells from a single position. A horrific Gothic-styled exterior of monumental masonry walls is broken at the center by a massive gatehouse whose slit windows underscored the impossibility of escape. Within, radiating spokes of cell blocks, lighted by skylights, created a new architectural form—the penitentiary that was among the most imitated of Philadelphia buildings with examples in Rome and across the nation, many by Haviland himself or his son Edward.

The building was the brainchild of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, which persuaded the Pennsylvania legislature to pay for their experiment in the effectiveness of separate or solitary confinement at labor to prevent prisoners from communicating with each other and thereby learning from each other. The sight of hundreds of prisoners laboring in silence attracted as many as 10,000 visitors a year. One was Charles Dickens, who wrote after his 1842 visit: “The System is rigid, strict and hopeless solitary confinement, and I believe it, in its effects, to be cruel and wrong.” Such criticism led to some relaxation of the solitary system, although it was not formally abolished until 1913. Nonetheless, despite the cruelty of the system, the prison was radically modern in its incorporation of ducted heat and piped water and sewage systems. Among its celebrity prisoners were Al Capone in 1929 (whose cell was outfitted with oriental carpets and fine cabinetry), and bank robber Willie Sutton. The prison closed in 1972 and is now a National Historic Landmark open to the public.