Marooned in a sea of tiny row houses, this marble leviathan is the culmination of the Greek Revival in America. It was the creation

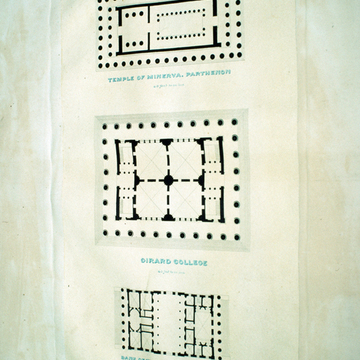

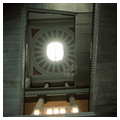

Together, Walter and Biddle devised an immense Corinthian temple surrounded by a continuous peristyle for the classroom building, its order taken faithfully from the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, as represented in Stuart and Revett's Antiquities of Athens (1762). This temple was flanked in turn by four white marble-clad buildings to serve as dormitories. All was vaulted in masonry, including the shallow groin vaults of the lower classrooms and the domical vaults of those above. The exterior is entirely of local marble—blue Montgomery County marble for the walls and white Chester County marble for the columns—even to the gargantuan roof tiles and ridge caps. Only for the underside of the peristyle, with its egg-and-dart-ornamented panels, did Walter switch to the less costly cast iron. When completed, it was the most expensive building in the United States—until it was surpassed by Walter's next great commission, the extension of the United States Capitol with its impressive central cast-iron dome.

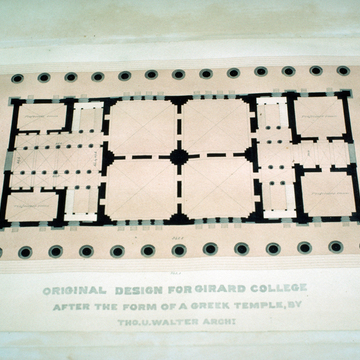

Immense doors provide access to a vast hall at either end of the building. Here self-sustaining cantilevered marble stairs with cast-iron balusters rise daringly the full three stories of the space. Girard's will specified the rather schematic plan: four classrooms per floor, each measuring fifty feet square. The use of the Greek temple form, which after all had no need of windows, proved disastrous, particularly on the top floor. Lighted at ankle height only by small windows at the top of the peristyle, or by small skylights at the top of the domical vaults (with their extraordinary echoes), the top floor was soon abandoned. In recent years the building has come to serve as a museum and an archive of the Girard family papers. It is remarkably well preserved (except, alas, for the decision in the 1950s to knock off all the volutes of the capitals after one broke loose and fell).

After the nation's centennial, the college grew. Girard graduate James H. Windrim designed a series of classroom buildings in the same white marble but in the more up-to-date Gothic style, all of which have been demolished for more contemporary buildings. Most important is Thomas, Martin and Kirkpatrick's Girard College Chapel (1931–1933), another marble-clad building but in a strikingly Moderne vein. Its oddly triangular plan responds to a shift in the street grid but also serves as a dynamic way of concentrating its sight lines.