Navajo settlement in the southwestern United States came late, probably in the sixteenth century, and is unusual in that it consists of dispersed family homesteads rather than the more customary villages found in most other native cultures in the area. The heart of the Navajo Nation lies in northwestern New Mexico and northern Arizona, but an extension is found bordering the San Juan River basin in southeastern Utah. Small homesteads dot the countryside throughout this region, and the one belonging to the Frank family is quite typical.

The Frank Family Homestead is located in the Mexican Water District just off U.S. 191 north of the Utah-Arizona border. The siting is modern, near a major highway, and oriented to four sacred points: Mount Taylor (south), San Francisco Peak (west), Hesperus Mountain (north), and Blanco Peak (east). According to Ellen Martin, the oldest of three daughters of Robert and Bertha James, who live on the site, the property was first settled in 1962 by the grandfather of their sister Pauline’s husband, Gerald Frank. Originally it was the Frank family’s summer camp; a winter camp lay several miles “due north,” and at one time the family moved seasonally between the two.

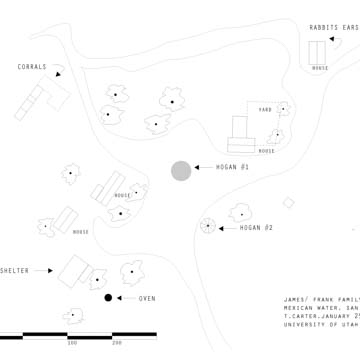

Like most Navajo homesteads, this one consists of numerous structures, including traditional hogans, ramadas (summer shade shelters), modern ranch-type houses, outdoor bake ovens (ornos), and sheep and horse corrals. The circular house known as a hogan (pronounced hoe-ghan and meaning “home” or “dwelling” place in Athapaskan) is the traditional Navajo dwelling. Seventeenth-century Spanish adventurers first noted their presence, and while now replaced by more modern ranch-type houses and trailers, they continue to play an important ceremonial role in Navajo culture. Most homesteads, like the Franks’, have at least one.

Hogans come in two main varieties, both referencing with their mounded shape the mountains sacred in Navajo mythology. The first is the “male” or forked-pole hogan, which is conical, and the “female” version, which is constructed of stacked logs with a more rounded dome-like shape. The Frank family hogan falls into the latter group. It was constructed by Duke Frank and Jack Tsosie, probably in about 1995, and follows a customary design. The plan is circular with the door facing east toward the rising sun (to catch the blessings of the first light). A ceremonial fire pit is placed in the center. A series of vertical earth-fast cedar posts support a roof of corbelled logs that rise toward an open smoke and ventilation hole. The corbelled structure is then packed with adobe clay to give the completed building a domed appearance.

Duke Frank also built a ramada on the homestead. The shade’s date is uncertain, though it may also have been constructed in the 1990s. It is used during the hot summer months for family gatherings of all kinds. Again, the plan and construction details are traditional, although in this case Frank used some modern materials, including welded metal posts and crossbars for the main structure. The vertical siding consists of log faces sawn from nearby ponderosa pine. Gaps have been left between the boards to allow for as much ventilation as possible. For the ceiling, two long metal poles run the length of the building and are covered with wire fencing. Next a series of log ratters are placed across the metal poles, and then an overlay of split ponderosa branches is added. This is packed with a sheathing of willows.

The outdoor oven was built in 2012. Such ovens were introduced into the Americas by the Spanish and were adopted quite readily by the native people in the Colorado Plateau region. They have become a traditional feature of Navajo homesteads. They are used primarily to bake bread for large ceremonial gatherings, although they are found with less and less frequency today. The Frank oven is constructed of corbelled dry-laid stone that has been covered with a coat of mud plaster. Flat stones are used to cover the door and smoke hole openings. The interior base consists of a layer of wood and charcoal packed down with six inches of clay. Bread is cooked by building a large fire in the oven. Then the hot coals are removed, the uncooked bread inserted, and the openings closed. Baking time varies, though the process is measured in hours and not minutes.