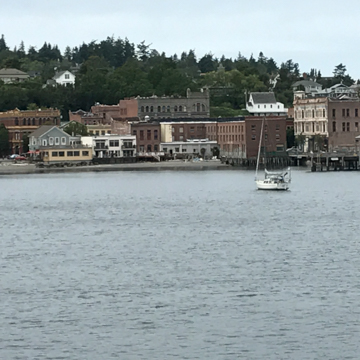

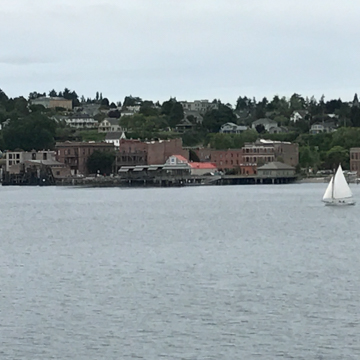

Port Townsend is located on the northeast tip of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, where the Strait of Juan de Fuca meets Admiralty Inlet. Surrounded by water on three sides, the town is perched on a bluff overlooking Port Townsend Bay. The port itself is a natural deep harbor, vital for the early shipping economy of the town and the Puget Sound region from which its characteristic built environment emerged.

The life of the city has been wrought with ups and downs, booms and busts. Its heyday was at the tail end of the nineteenth century, when an economic and population boom saw the rise of many Victorian-era residences and commercial buildings for its business tycoons. The relatively abrupt end to its early prosperity left many buildings vacant and untouched. The styles range from simple Cape Cod to Gothic and Queen Anne, among others. Port Townsend proudly boasts an impressive number of restored and preserved buildings, which are almost all rooted in the city’s history as an early port of entry to Washington Territory.

The Klallam and Chimacum tribes are believed to have been the original settlers of what later came to be known as Port Townsend—their numbers thought to have reached around 500, according to James McCurdy’s account of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, the trading ship George Emery began making regular stops by the port as it sailed between San Francisco and Puget Sound, collecting lumber to help build and re-build the fast-growing California city. In August 1850, a ship clerk named Henry C. Wilson disembarked at Port Townsend and filed the first donation claim on the western shore. Although he did not settle immediately, Wilson’s is the first recorded legal claim on Indian land in Washington.

In 1851, the first log cabin was erected by Alfred Plummer and Charles Bachelder, single men who had been passengers aboard the George Emery. Plummer and Bachelder’s settlement was followed by that of two businessmen, Francis W. Pettygrove and Loren B. Hastings. Pettygrove had moved to Oregon Territory in 1843, co-founding the city of Portland. He and Hastings moved together to California in 1849 to sell supplies to gold seekers during the Gold Rush. Together, all four men decided to create a partnership and form a town in Port Townsend in 1852. Plummer, Pettygrove, and Hastings opened a trading post and fish business from a warehouse, establishing the first commercial enterprise in town. More settlements followed, and soon members of the Klallam tribe were asking to be compensated for the land that was being taken. By 1852, there were three families and fifteen men living in Port Townsend, as relations with the Klallam grew tenser.

Around the same time, on December 22, 1852, Jefferson County was incorporated into Oregon Territory and Port Townsend was named the county seat, but it is disputed if Port Townsend was even legally a town. The first plat was filed in 1856, although the first legal claims were made in 1852 and some sources argue there were plats made in the same year. By March 1853, Washington Territory was created and in 1854 the Puget Sound Customs Collection District moved from Olympia to Port Townsend. As a stopping point for shipping, the town soon blossomed.

Selected by the territorial government as the principal port of entry for Puget Sound shipping in 1854, the city thrived despite that designation shifting to Port Angeles, further to the west, from 1862 to 1866. As the port of entry, all ships had to harbor in town for inspection, and local industry thrived on the maritime business. Locals soon envisioned Port Townsend as the major “city of Puget Sound” and optimists were calling it “Key City” or even the “New York of the West.” In 1858, the first general store was opened by German immigrant David C. H. Rothschild. By 1860, with 264 people, Port Townsend had already become the seventh-most populated town in all of Washington Territory.

The Civil War slowed the economy, but maritime activities together with agriculture and logging kept Port Townsend commercially afloat. By the 1870s, there were rumors of connecting the town to larger cities via railroad, and a building boom ensued despite the Northern Pacific Railroad ultimately ignoring the advice of James Swan (agent and secretary to territorial governor Isaac Stevens) and choosing Tacoma for its railroad line terminus in 1890. Still, between 1880 and 1890, the population increased by over 400 percent to more than 7,000 people, and the dream of a railroad did not die. The hope for a railroad inspired a flurry of investment and construction, particularly in the last years of the 1880s, and it is this period that characterizes the built environment of present-day Port Townsend. Buildings of nearly every style common to the nineteenth-century American West, from the Richardsonian Romanesque to the Queen Anne, were erected in Port Townsend, and for every imaginable building type. Very few buildings were designed by professional architects; most were designed by carpenter-builders whose variegated and occasionally idiosyncratic architectural touches suggest they may not always have been working from stock plans or pattern books. An open-air vernacular museum of late-nineteenth-century architectural styles is still very much intact on the streets of Port Townsend, even if many of the buildings did not enjoy the immediate economic prosperity their developers or builders imagined for them.

The Panic of 1893 finally ended hopes for a railroad line in Port Townsend altogether. The collapse of the Oregon Improvement Company, which had promised to bring the Union Pacific Railroad to Port Townsend, together with the growth of Seattle and Tacoma as competing port cities, sent Port Townsend’s population spiraling into rapid decline. A quarter of the population left Port Townsend in the ensuing decade, and the downtown streets and residential areas were left with several impressive commercial structures, civic buildings, and residences that were only partly occupied or empty. For the much of the early twentieth century, the town featured little commercial activity, and in 1913, Seattle wrested the title of the state’s official “Port of Entry” from Port Townsend. In 1927, the town’s population made a brief comeback when Crown Zellerbach Corporation built a kraft paper plant on the town’s outskirts. Today this corporation remains the largest employer in the area.

Because of the relatively short timeframe in which Port Townsend prospered and fell and no major economic boon allowed for urban expansion, reconstruction, or renewal for the next 100 years, its many Victorian-era homes and commercial buildings have been left largely untouched. The relative lack of economic progress and its small population (Port Townsend had 9,255 people in 2014) has allowed for the preservation of the city’s historic architectural stock. This took effort, however. In the early 1960s, community members began to realize the benefit of Port Townsend’s existing built environment. The first “Homes Tour” took place in 1963, featuring only one home, the Saunders House. Planners expected a couple hundred spectators at most, but over 2,000 showed up. The Homes Tour expanded and became a popular annual tradition. By 1970, the city government, the Port of Port Townsend, and smaller community groups within the city began to work to gain recognition for its historic properties. This led to an area roughly bounded by Scott, Walker, Taft, and Blaine streets and the waterfront to be designated as a National Register Historic District in 1977, although more than twenty-five individual properties and sites have been listed beyond the district.

In addition to a specialty boat-building industry and the paper mill, the economy of the city today largely relies upon tourism that has been spurred, in part, by historic preservation. In 2000, Port Townsend was awarded the Great American Main Street Award for its preservation-based economic revitalization efforts.

References

“Ann Starrett House.” PT Guide. Accessed July 18, 2017. http://www.ptguide.com/.

Bermant, Charlie. “Port Townsend Library Turns a Chapter with Reopening of its Carnegie Library.” Peninsula Daily News(North Olympic Peninsula, WA), August 4, 2014.

Caldbick, John. “Port Townsend – Thumbnail History.” Essay 10752. HistoryLink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, May 5, 2014. Accessed November 30, 2015. www.historylink.org.

Clise, Pam McCollum. “History of the Port Townsend Library.” Peninsula Daily News(North Olympic Peninsula, WA), April 24, 2008.

Dickerson, Paige. “Spook-tacular ghost stories of the Peninsula.” Peninsula Daily News(North Olympic Peninsula, WA), October 30, 2007.

“Francis W. James House.” PT Guide. Accessed July 18, 2017. http://www.ptguide.com/.

Holva, H.J., and Steve Franks, “Port Townsend MPO,” Jefferson County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1991. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Hunt, Mrs. (Dorothy) Gerald A., “James (Francis Wilcox) House,” Jefferson County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1970. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Hunt, Mrs. (Dorothy) Gerald A., “Rothschild House,” Jefferson County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1970. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Hunt, Mrs. Gerald A., “Starrett House,” Jefferson County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1970. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

“John Trumbull House.” PT Guide. Accessed July 18, 2017. http://www.ptguide.com/.

Krafft, Katherine, and Shirley Courtois, “John Trumbull House,” Jefferson County, Washington. Community Cultural Resource Survey-Inventory Form, 1984. State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Washington.

Marez, JoAnne. “Port Townsend: Historic and Comfortable.” The Kitsap Sun(Bremerton, WA), September 19, 1997.

McAlester, Virginia, and Lee McAlester. A Field Guide to America’s Neighborhoods and Museum Houses: The Western States.New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

McClary, Daryl C. “Victor Smith Forcibly Moves the U.S. Customs Port of Entry for Washington Territory from Port Townsend to Port Angeles on August 1, 1862.” Essay 7474. HistoryLink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, September 21, 2005. Accessed December 31, 2015. www.historylink.org.

McCurry, Alex. “Historic Property Inventory #107902.” State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Washington. Accessed July 7, 2017. https://fortress.wa.gov/.

Pitts, Carolyn, “Port Townsend Historic District,” Jefferson County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, 1977. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Reece, Daphne. Historic Houses of the Pacific Northwest.San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1985.

“Rothschild House.” PT Guide. Accessed July 18, 2017. http://www.ptguide.com/.

“Rothschild House History.” Jefferson County Historical Society. Accessed November 22, 2015. http://www.jchsmuseum.org/.

“US Post Office.” PT Guide. Accessed July 18, 2017. http://www.ptguide.com/.

Vandermeer, J. H., “Port Townsend Carnegie Library,” Jefferson County, Washington. Community Cultural Resource Survey Inventory Form, 1981. State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Washington.

Woodbridge, Sally B., and Roger Montgomery. A Guide to Architecture in Washington State: An Environmental Perspective.Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1980.