You are here

Claquato Church

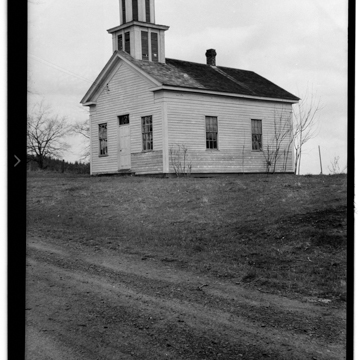

Loosely resembling a small-scale meetinghouse common to Puritan settlements in New England, the Claquato Church is the oldest surviving church in the state and, completed in 1858, one of its oldest buildings. Whether its builders were looking specifically to New England prototypes is unclear, but such architectural connections may have provided the settlers, many of whom hailed originally from the Eastern Seaboard and the Midwest, with the assurance that they were not entirely removed from the cultural and spiritual traditions of the older “New World.” The church is an excellent example of a building erected by early settlers for community use, and it played an important role in the social and religious life of the Claquato settlement in the first years of Washington Territory.

In 1858 local settlers erected the small 20 x 30–foot, one-and-a-half-story wooden church, originally for Methodists, on land owned by Indiana-born Lewis H. Davis, the first settler and a prominent road builder in the Claquato area. Davis, along with his brother-in-law, J.D. Clinger, also apparently supervised church construction. The whipsawn board siding came from a sawmill built and owned by Davis; the village blacksmith forged many of the larger nails; and Clinger fashioned the doors and the casings. Settlers in nearby Boistfort produced the pews, pulpit, and pastor’s chair. The belfry, perhaps the church’s most distinctive element, is a louvered square upon which is superimposed a smaller louvered octagon. Its pinnacle is marked with a symbolic wooden crown of thorns in place of a Latin cross or simple spire—somewhat uncommon in church design at the time. The belfry sprung from what the writers of Washington: A Guide to the Evergreen State in 1941 described as “lookouts” that featured “mortise and tenon work of high quality.”

Davis had stipulated in the deed that the church, much like a Puritan meetinghouse, would serve multiple functions as a place of worship, a school (known as Claquato Academy), and a meeting space for the small community. Formally, its similarities to a meetinghouse are in its symmetry; its wooden pews, pulpit, and floors; and its singular steeple over the entrance. Its location—although more difficult to recover today because of surrounding development—bears similarities to the elevated sites of New England meetinghouses, as well: it sits on a slightly raised plain above Mill Creek and the Chehalis River, and would have been clearly visible to early Washington Territory settlers as they arrived either by boat or wagon. An even more direct connection to New England is the bronze bell that hangs in the belfry: this was cast originally in Boston by Henry A. Harper and Company in 1857 and transported to Claquato by ship via Cape Horn.

The church was not necessarily the first building in the Claquato settlement, but it appeared at a relatively early stage in the settlement’s history. In 1853, Davis filed for a land claim of 640 acres in the newly formed Washington Territory, including that of Claquato Hill, where the church stands. He first built a one-room house for his family on Claquato Hill, then later a sawmill that produced lumber for the growing community. Davis attracted settlers to the area in part because of his ambitious acquisition of national and territorial grants for road building—notably the main north-south Military Road arterial that connected ships on the Columbia River to the territorial capital in Olympia.

The hamlet of Claquato grew quickly as an important way station for the overland trade from the Columbia to the Puget Sound. By 1858, the same year the church was erected, the town featured two hotels, a general store, stables, a blacksmith shop, and a carpenter shop, and it had become the largest settlement between Olympia and the Columbia River. It was also named the county seat for Lewis County.

Claquato prospered until the new settlement of Saundersville, a few miles away, was chosen in 1873 as a stop along the Northern Pacific Railroad line from Kalama to Tacoma. Separated from the railroad, Claquato began a steady decline that saw a new school built on the opposite side of the Chehalis River to the south and, in 1879, the transfer of the county seat to Saundersville, which was renamed Chehalis. Today, Claquato is no longer a municipality, but the church and a nearby cemetery mark its presence.

Services were held in the church until 1930 when it ceased to belong to any religious group or denomination. It then stood empty and became the target of vandalism until ownership was transferred to Lewis County in 1952. The Claquato Church was restored by the American Legion in 1953 and rededicated as a memorial to the early European-American settlers of the Claquato area. Surviving early-twentieth-century photographs suggest that the church exterior, with its sash windows, central door, cornice returns, and pilasters, remains essentially in its original condition.

References

Backman, James O., “Claquato Church,” Lewis County, Washington. National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form, 1972. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

“The Successor of the Train: The Early Trails and the Road Between Pacific and Western Lewis Counties.” The Sou’wester41, nos. 2 & 3 (Summer 2006 and Fall 2006): 10-11.

Welsh, Robert L. The Presbytery of Seattle: 1858-2005: The “Dream” of a Presbyterian Colony in the West.Self-published. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Corporation, 2006.

Writers’ Program of the Work Projects Administration in the State of Washington. Washington: A Guide to the Evergreen State.Portland, OR: Binfords and Mort, 1941.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.